10 Man-Made Organs

The liver is one of the most abused organs in the body, suffering damage from overindulgence in alcohol, drugs, improper diets, and more. As it stands, there are no effective artificial liver replacements available, save for perhaps a few work-in-progress attempts like the ELAD. But the good news is that the demand for a remedy has not fallen on deaf ears. Takanori Takebe and his team from Yokohama City University in Japan have recently mixed the cells of a liver with the cells of umbilical cords, resulting in a small but seemingly functional liver bud. It seems scientists have been developing lab-grown organs since as early as 1988 and have had limited successes with bladders, hearts, and kidneys. A key benefit this method will offer patients is that their new organs will be tailor-made from a harvesting of their own cells, which will omit the need for the anti-rejection drugs that are currently required. While we shouldn’t discredit this phenomenal scientific achievement, we should still be wary: critics have suggested that the results of Takanori’s liver replicas are unconvincing, both because the liver cells don’t seem to be much different than the notoriously cancer-conducive organ cells artificially produced in the past, and because the experiment Takanori used to demonstrate how the livers functioned on mice went on for only one month—which they say isn’t enough time to confirm whether or not the cells were cancerous. There’s also the issue of incompletion, since these organs are too undersized to back up an entire human body at present. Perhaps the most salient problem is that man-made organs (like everything man-made) are unpredictable, and have the potential to malfunction at any given time. Which, as you can imagine, would be rather a disappointment to the person who was in the middle of using that liver to stay alive.

9 Bionic Humans

We’re all simultaneously awaiting and dreading the dawn of machinery taking human form. Rex, the robotic exoskeleton, is one million dollars’ worth of the latest developments in human prosthetics and artificial organs. The 2.0-meter (6.5-ft) tall robot encompasses an artificial spleen, pancreas, trachea and kidney, as well as a battery-powered heart, infection-free synthetic blood, and a realistic face that eerily resembles one of his creators. Watch this video on YouTube Modeled after psychologist Bertolt Meyer—who wears a bionic hand himself—Rex has been designed for a display at London’s Science Museum, as well as a documentary entitled How To Build A Bionic Man. For the unsettled public, Meyer additionally mentioned that there’s no risk of a Terminator episode unfolding, or in his own words: “I’d say it’s highly unlikely that, in our lifetime or in that of our grandchildren, we will see a fully articulate human body with an artificial intelligence.”

8 Remote Control Brains

This little fun fact of science isn’t even new: in 1963, it was discovered by Yale researcher Jose Delgado that neurons in the brain can be electrically stimulated to control involuntary limb movement, manipulate feelings, or, even more impressively, halt a bull mid-charge. Jose demonstrated this by standing in a ring, accompanied by an angry bull. He allowed the animal to thunder towards him, and then ended its aggressive charge at the mere push of a button. An implanted device he called a “stimoceiver” was responsible for this phenomena, communicating electronic pulses that placated the animal via its brain neurons. Of course, modern development for this sort of brain control on human beings is more likely to look at regaining control of parts of the brain rendered dysfunctional after victims suffer strokes or brain damage, as well as providing platforms for cures concerning diseases previously thought incurable, like Parkinson’s disease. Still, I shudder to think of brain control’s latent potential. Call me a cynic.

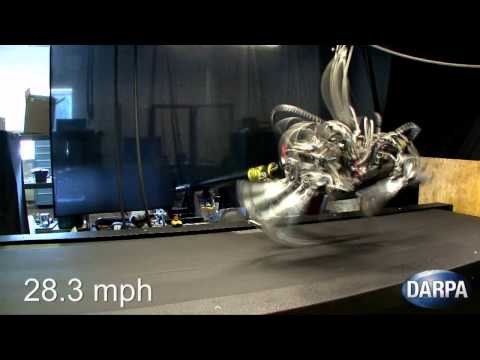

7 War Robots

It is grievously apparent that members of the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) do not watch science fiction movies. Why else would they model a war machine after a cheetah? So if it flips a switch and goes haywire, you can’t outrun it? Military robots are being designed to harness the natural abilities animals have developed over centuries of evolution. The cheetah robot is one of the latest models of war robots to join the ranks. It doesn’t look much like a cheetah, but it’s got the agility, speed, and locomotion of 28.3 mph for a 20-meter (65-ft) split to convince you that it’s as close as any robot has ever gotten. Just in case you’re unaware, that’s faster than Usain Bolt’s first-place universal record for running (although to be fair, the inclusion of a treadmill in the cheetah’s case meant that most of its strength went into swinging its legs, not into actual propulsion). If a cheetah isn’t enough to worry about, it’s already been accompanied by a robot called Big Dog whose design originally imitated a pack mule. Of course, carrying weapons of mass destruction wasn’t a glorious enough feat for Big Dog, so Boston Dynamics went ahead and added a mechanical arm that enables it to lob cinder blocks at warehouses, and (I’m assuming) people. Big Dog is now voice-controlled, allowing soldiers to effortlessly deploy it on the battlefield. It can run along and use its prodigious strength to lift debris off fallen soldiers and hurl it at their loser, cheetah-less enemies.

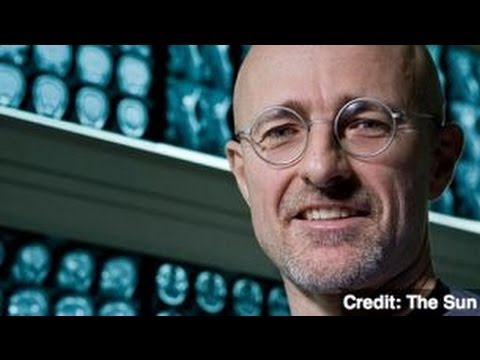

6 Human Head Transplant

Not to be mistaken with a brain transplant, this procedure requires the entire, decapitated head of one person to be replaced on the decapitated body of another (preferably with consent from both parties, but you could go the evil scientist route as well). Effective head transplants were more of a theory than a possibility until recently, due to the obstacle of reattaching the fragile bonds of the spinal cord. Now the discovery of a nerve regeneration method has been revealed in the US, and scientists predict that human head transplants will soon be a viable option. Watch this video on YouTube So far, successful transplants have been performed on rats, dogs, and monkeys, although without a means to reattach the spine at the times of the operations, the attached heads were unable to control their new bodies. If you’ve ever seen the twin-headed dogs, or the adult rats with baby rat heads screaming off their thighs, you might think it’s dubious to call this development in any way successful. In principle, it’s intended to help people who have incurable ailments or diseases, too many organ problems for surgical intervention to solve, or who are quadriplegic. Of course, since the procedure has never been tested on humans before, who knows what the implications might be. Will you even be the same person by the time you’re Frankenstein-ed back together?

5 Google Glass

Google glasses are indeed available now (probably not to you, but to somebody). The glasses themselves are not nearly so disturbing on their own. It’s the ideas they’ve incited that are in question. Google Glass will enable us to do everything we’ve been doing on our cell phones, but in a sophisticated, hands-free, much more James Bond kind of way. Intriguing as they are, we should have known by now that anything created in the pursuit of science is never the end; it’s only the beginning. One Google futurist has already predicted we’ll be uploading our brains into computers next, and while the ability to do so remains indefinite because the imaging required to achieve retention of consciousness into a digital space is unheard of, the computer element may not be as far off as we would imagine. And don’t just laugh that off as hopeful science fiction material. We put a man on the moon, didn’t we? Immortality inside a machine is one thing, and the opportunity to transcend the way humans process thought is another. But don’t you think the brain would be traumatized to realize it was unattached to all the bodily elements it is designed to handle, instead finding itself to be merely suspended data stored electronically? When that human mind discovers it’s in a machine, how long before it succumbs to insanity? Or will it be like some sort of “brain in a vat” situation that philosophy warned us about, in which the brains aren’t aware they are in the computers? Who knows, maybe it’s already happened. Maybe you just think you’re reading this because some mad scientist has programmed your isolated brain to let you think you’re reading this. And if that doesn’t make you think, then what about the suggestion that our natural human bodies will be replaced by machines in just 90 years? That’s another bold speculation Google engineers have made, and judging by Google Glass and the avid claims of its creators, they’re serious.

4 Genetically Modified Babies

While genetically modified babies are predicted to avoid unwanted diseases and disorders, the concept seems too full of gaping holes right now to be considered secure, even though we have genetically modified both food and animals in the past. It should be remembered that although we successfully developed these modified organisms in the end, it was not without trial and error—emphasis on error. While disposing of “failed” artificial plants or animals may be frowned upon, it does happen, and mistaken human prototypes in this game of chance would make the discarding process suddenly grossly more unethical. And yet, genetically modified babies have already been brought to life. These children have inherited extra genes—one from a man, and two from women—among other aberrations. Consequences were soon to follow, and things weren’t as sunny as the scientists would have liked. By the time the children were teenagers, reports began to sprout of how the additional genetic trait might express itself either in the individual, or in the individual’s subsequent children. A frequent rise in autism seemed to be one of the ramifications noted. Unfortunately, many of the babies born this way weren’t properly evaluated or followed up on, making a safe conclusion impossible. The FDA is leaning toward a ban on so-called designer babies, doubtless to appease the rabble. While many argue that the GM children are growing up just fine, a brief glance at some of the controversial results genetically modified foods have already been accused of exhibiting will probably make you glad for the FDA’s final ruling. Perhaps we should perfect plant engineering before taking on genetic intervention in human life. If it makes you feel any better, scientists have confirmed that “a new super race of genetically perfect beings with enhanced intellect and strength” is neither the aim, nor even possible. Yet.

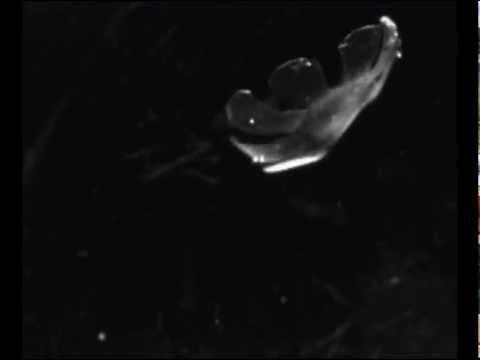

3 New species

A rat jellyfish is something you don’t hear about everyday, but thanks to a team of scientists at Harvard University, you can now witness the artificial rat jellyfish undulating away as though it were the real thing. While the creature may act like a jellyfish and look like a jellyfish, it is genetically engineered from the cells of a rat. And that’s not even the weirdest thing: the next jellyfish being considered will be made from the cells of the human heart to test the reactions of heart drugs. Our influence over genetic creation is staggering. If we’re able to create this organism now, what will we be creating further into the future? We’ve thought up several innovative ways to improve the world through our own genetic creations before, for better or worse. A more primitive instance of our attempt to forge a new species would be the crossbreeding of animals: in 1956, a veritable attempt to breed a “super bee” resulted instead in the dangerous creation of the killer bee. It will be interesting to see what else our increasing power over genetics will birth into this world.

2 De-Extinction

Many scientists believe we owe some kind of penance to the world for terminating a few of its species, and that de-extinction is the answer. De-extinction is the cloning of extinct animals from DNA extracted from museum specimens or preserved tissue samples. While scientists are hoping to bring back an assortment of lost species, including the mammoth, there are obvious objections: some ecologists argue that the funding required for de-extinction will detract from the funding available for conserving existing species. Compelling as the idea of de-extinction may be, it prompts the nervous question as to whether this might not turn out like Jurassic Park. Even if it doesn’t, there are many other more probable repercussions to consider. Remember, a species that died millions or even thousands of years ago will be reborn into a world that has changed considerably from the environment it was biologically suited to handle. We don’t live in an ice age anymore. In fact, we’re heading for the greenhouse effect. So the bottom line is, yes, we could bring back the mammoth. The only qualm would be that science is about thinking ahead, and that’s not really thinking ahead when you consider that we have nowhere stable to put a mammoth. There are admittedly some better ideas for de-extinction candidates, including the ground sloth, which you probably didn’t even realize was extinct until you watched Ice Age.

1 Talking Apes

If a small alteration in the genome could enable chimpanzees to speak like humans do, what would become of sentience? To avoid that interminable squabble, let’s skip to the facts: genetically speaking, chimpanzees resemble humans more than any other animal on the planet. We share 98.5 percent of our DNA with them. So just how close does that make us? If you haven’t heard the story of “Washoe” yet, read into it. The short version is that a chimpanzee in the 1960s not only learned and applied approximately 350 words of American Sign Language, but also passed on some of her teachings to her adopted chimpanzee son, Loulis, completely without human intervention. During the 42 years of her life, it has been said that Washoe “broke the barrier” between human and animal communication. Despite this grasp of communication, chimps remain physically incapable of producing the sounds that constitute human speech. This comes down to a single gene known as FOXP2: chimpanzees have a slightly different variation of the FOXP2 gene than humans, but they have it nonetheless. Of course, this isn’t the only gene responsible for speech—and it alone might not prompt the desired effect—but the bridge is being built. This leads to the question of whether tampering with the genetic instructions of their code could result in speaking chimps. Is it possible? Probably. Is it a good idea? Maybe not so probably. Shouldn’t we be concerned about what the chimps will have to say? What if they start using bigger words than us? What an ego bruise that would be. And perhaps more disconcertingly, what excuse will we have to give them for the monkey head transplant we tested out on them earlier?