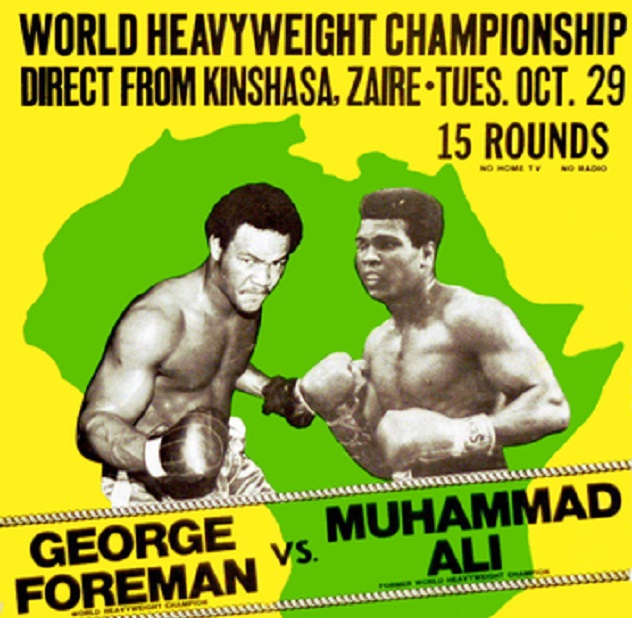

10The Rumble In The Jungle

The Rumble in the Jungle is one of the greatest sporting events of all time, featuring an unstoppable Muhammad Ali in a triumphant knockout victory over his rival, George Foreman. In fact, the fight is so legendary that people tend to forget that the whole thing took place under the auspices of one of the 20th century’s most notorious dictators: Mobutu Sese Seko. Zaire’s kleptomaniac ruler was so eager to stage the fight that he even put up a $10 million purse. The money was all stolen from the people of Zaire, but Mobutu was a close US ally and reporters covering the fight “did not ask many questions.” To make sure the event went swimmingly, the story goes, Mobutu even had all the known pickpockets and criminals of Kinshasa executed. Meanwhile, conflict raged elsewhere in the country and the fight took place with armed soldiers looking on. Even the stadium where the fight took place had been used as a makeshift prison camp/torture chamber, and it was rumored that they had to scrub it clean of blood before the fight. In the end, Mobutu’s attempt to use the fight to drum up good publicity for Zaire didn’t go quite as he’d hoped. Reportedly, his officials were infuriated by Ali’s televised boast that: “All you boys who don’t take me seriously, who think Foreman is going to whup me; when you get to Africa Mobutu’s people are going to put you in a pot, cook you, and eat you.”

9The 1968 Summer Olympics

In 1968, Mexico City was abuzz with preparations for the 1968 Summer Olympic Games. But beneath the surface, all was not well. Young Mexicans were fed up with poverty, corruption, and a repressive government. The decision to spend $150 million on the Olympics brought things to a head and protests soon broke out, mostly calling for the repeal of laws allowing the arrest of anyone who attended a meeting of more than two people. On October 2, just 10 days before the Olympics were due to start, 10,000 students gathered in Tlatelolco Square, chanting “We Don’t Want Olympics, We Want A Revolution!” The government response was immediate and brutal. The military surrounded the square and opened fire, while armored cars rumbled into the mass of students. A subsequent cover-up means the exact death toll remains uncertain, but it’s clear that it was a slaughter, with as many as 300 deaths. Hundreds more were rounded up, imprisoned, and tortured in the aftermath. At the time, the military insisted they had only fired after being shot at from the crowd, but this is now considered unlikely. Despite the bloodbath occurring just across town, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) declined to move or postpone the games, noting that the violence wasn’t aimed at the Olympics themselves. As IOC head Avery Brundage had earlier explained: “If our Games are to be stopped every time the politicians violate the laws of humanity, there will never be any international contests.” Brundage, nicknamed “Slavery Avery” for his known racist views, wasn’t quite so sanguine when Tommy Smith and John Carlos famously gave the Black Power salute on the podium later on in the games, threatening to ban the entire US team if they weren’t sent home immediately.

8Equatorial Guinea’s African Cups Of Nations

Under the brutal rule of Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo, Equatorial Guinea has one of the worst human rights records on the planet, with opponents of the regime regularly tortured and murdered. An oil boom has theoretically made the country rich—GDP per capita is around $25,900—yet the vast majority of the population lives on less than $2 a day. The rest of the money is stolen by the ruling family and their cronies. Obiang’s son is estimated to have bought at least $3.2 million worth of Michael Jackson memorabilia alone. He also recently considered buying a yacht for $380 million, almost three times Equatorial Guinea’s yearly health and education budgets. Some of the money also went to co-hosting the 2012 African Cup of Nations, one of the most prestigious tournaments in world football. To prepare for the tournament, the regime spent millions of dollars building and refurbishing stadiums (the exact cost was not released). It also cracked down even further on civil liberties and openly harassed foreign reporters who tried to cover anything other than the tournament itself. Amazingly, Equatorial Guinea was chosen to host the tournament again in 2015, after Morocco pulled out at the last minute due to Ebola concerns. (Although the Equatoguinean team was technically banned from football for cheating at the time, this was politely overlooked.) This required spending tens of millions building two further stadiums. It also apparently required arresting opposition activists. Despite the growing condemnation of the 2022 World Cup in Qatar, there has been little international outrage about holding the Cup of Nations in a country with an even worse record on human rights.

7The 1982 African Cup Of Nations

Of course, the Cup of Nations does have something of a track record when it comes to letting monstrous dictatorships host. Take the 1982 tournament, which was held in Muammar Gadhafi’s Libya, already a something of a regional pariah for its military intervention in Chad. Ironically, Gadhafi hated football and had even closed the Libyan league down from 1979–1982. (In one version of the story, the dictator became insanely jealous after seeing the names of popular footballers written on a wall in Tripoli.) He agreed to host the 1982 Cup to further his diplomatic goals but still insisted on opening the tournament with the stirring words: “All you stupid spectators, have your stupid game.” Sadly, not everyone in Gadhafi’s family felt the same way. His son Al-Saadi actually loved football so much he decided to become a professional player. He wasn’t talented enough, but you don’t need talent when you’re a rich maniac with your dad’s army to back you up. Soon Al-Saadi was the star striker in a Libyan league so heavily rigged in his favor that announcers were forbidden from saying the names of any other players. If a team tried to protest the obvious cheating, they would be forced to keep playing at gunpoint. Al-Saadi’s glittering career only took a nose-dive when he leveraged Libya’s oil money to engineer a hilariously corrupt move to the Italian top division, where he played for less than half an hour over three years, failed a drug test, and was voted the league’s worst player ever. He is currently on trial in Libya for murdering a rival footballer.

6The 33rd Chess Olympiad

Kirsan Ilyumzhinov, president of the Russian Republic of Kalmykia, loved chess. He loved it so much he built a gleaming multimillion-dollar facility known as Chess City and inaugurated it with the 33rd Chess Olympiad in 1998. (Shown above is the official mascot of the event.) How impoverished Kalmykia could afford this isn’t clear, and a local journalist named Larisa Yudina was stabbed to death shortly after opening an investigation into the matter. Local activists were beaten for protesting the expense, with one leader briefly thrown into a mental hospital and then forced to flee Kalmykia. None of this was allowed to put a dampener on the tournament, with over 1,000 top international chess players ignoring calls for a boycott to enjoy the luxurious hospitality and the offer of a thoroughbred Kalmyk horse for every winner. The luxury came at a price, with Ilyumzhinov reportedly diverting child welfare money to finish Chess City in time. Kalmykia’s crumbling highways were ignored in order to pave the roads leading to the venue, which ordinary Kalmyks were banned from driving on. Meanwhile, every Kalmyk organization had to sponsor a team, which effectively meant emptying government buildings to furnish the players’ quarters. Experiences varied: “The Statistics Committee got Peru. The apartment had been used by the construction workers, and it was a huge job fixing it up. As for the local publishing house, they got Tajikistan, and they were happy. The Tajiks weren’t used to much comfort, and it was easy to take care of them.” Ilyumzhinov is still president of the World Chess Federation and is best known for his belief in aliens and his bizarre attempts to bring peace to conflict zones through the medium of chess.

5The 1978 World Cup

After a military coup in 1976, Argentina was ruled by a brutal right-wing junta which murdered thousands of opponents during the so-called “Dirty War” that followed. Argentineans suspected of left-wing leanings were regularly kidnapped, tortured, and thrown out of planes into the ocean. But that didn’t stop FIFA from allowing Argentina to host the 1978 World Cup, giving the junta a valuable shot at some good publicity. They seized it with both hands, hiring a pricy PR agency and even building special walls so that visitors wouldn’t be able to see the impoverished slums of Buenos Aires. In the buildup to the tournament, any remaining dissidents and potential troublemakers were kidnapped or murdered. Even the tournament’s head organizer, General Omar Actis, was assassinated, allegedly for opposing the government’s wild spending. The tournament itself was not a classic, with the junta widely alleged to have rigged games—35,000 tons of grain and $50 million in credit supposedly got them a 6–0 win over Peru. Despite the junta’s crimes, only one player, West German hero Paul Breitner, declined to play on moral grounds. As Argentina’s star striker, Leopoldo Luque, put it years later: “With what I know now, I can’t say I’m proud of my victory.”

4Dennis Rodman’s All-Stars

At this stage, there’s almost no point in listing the monstrous crimes of the North Korean government. The state has become a such a byword for drab cruelty and oppression that it’s easy to forget just how genuinely nauseating life there can be. At least, that’s the charitable interpretation of former NBA star Dennis Rodman’s actions. Rodman, who is on the record with his belief that North Korean leader Kim Jong-un is “an awesome guy,” has made several trips to North Korea and actually organized a team of retired NBA stars to play a game there as a “birthday present” for Kim. Needless to say, the game attracted a fair amount of controversy. The NBA distanced itself, arguing that while “sports in many instances can be helpful in bridging cultural divides, this is not one of them.” Meanwhile, Congressman Eliot Engel pleaded for the “bizarre and grotesque” tour to be called off. For his part, Rodman apparently had no worries about organizing a PR stunt for the dictatorship, explaining: “I’m not a president, I’m not a politician, I’m not an ambassador. I’m just an athlete and the reason for me to go is to bring peace to the world, that’s it.” The North Koreans apparently won the game. Peace has yet to break out.

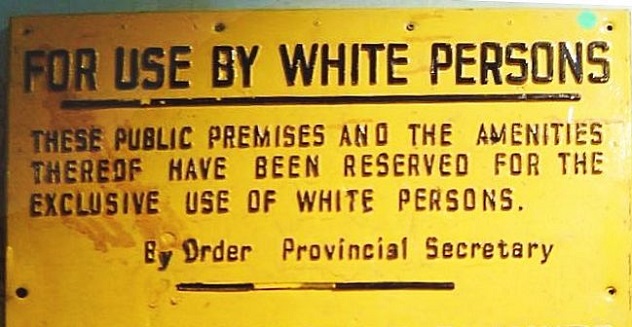

3The Rebel Tour Of South Africa

By the early 1980s, South African cricket was in a crisis of its own making. Under apartheid, the country’s cricket team had long refused to play against non-white teams. In 1969, England’s attempt to field a non-white player, Basil d’Oliveira, caused such a dispute that the whole tour had to be abandoned. Meanwhile, opponents of apartheid called for a sporting boycott of the brutal regime. In 1970, South Africa was officially banned from international cricket. As their beloved team stagnated without quality opponents, the South Africans changed their tune, desperately trying to lure anyone who was willing to play them. An unlicensed English team toured in 1982, followed by a “rebel” Sri Lankan squad a year later. Over in the Caribbean, things couldn’t have been more different. The West Indies were unquestionably the best team in the world, partnering devastating fast bowlers like Joel Garner and Michael Holding with such formidable batsmen as Desmond Haynes, Gordon Greenidge, and the sublime Viv Richards. The world had never seen such a combination of pace, power, and talent. In fact, the West Indies team was so good that many world-class players never even made it onto the team. To make matters worse, there was little money in cricket in those days, and many players struggled to make a living in the off-season. When the South Africans began offering players $120,000 for a single tour, many found it hard to resist. In 1983, 18 West Indian cricketers agreed to a tour of South Africa. Many were players frustrated by their inability to break into the West Indian first team, but the squad included such big-name players as fast-bowler Colin Croft, wicketkeeper Alvin Kallicharran, and 1979 World Cup hero Collis King. All were given “honorary white” status for the duration of the tour. It was a decision they would regret for the rest of their lives. Although the rebel cricketers insisted that their tour had helped break down racial barriers, all 18 immediately became pariahs in the Caribbean. West Indians were outraged that their cricketing heroes would collaborate with apartheid South Africa for money. The entire team was banned for life (the ban was eventually lifted in 1989) and most never played cricket at a high level again. Shunned wherever they went, most of the rebels had to leave the region and at least three had major mental breakdowns. Richard Austin, one of the most versatile players of his generation, currently begs on the streets of Kingston. The West Indies team continued to dominate world cricket until the 1990s, by which time apartheid had ended and South Africa had rejoined the cricketing world.

2The 2015 European Games

This week, the inaugural European Games will be hosted in Azerbaijan. The multi-sport event, including swimming, gymnastics, and athletics, will essentially be a mini-Olympics, along the line of the older Asian Games. It should be a wonderful event, with just one hitch—Azerbaijan is a deeply repressive crypto-dictatorship, ranked 126 in the world for corruption and 162 for press freedoms. Another report estimates that Azerbaijan is the fifth-worst country in the world when it comes to censorship. As you’d expect, the buildup to the games, which will cost Azerbaijan over $1 billion (the full cost hasn’t been revealed, but the stadium alone is at least $600 million), has been marred by widespread repression. More than 40 people have been arrested for investigating corruption surrounding the games, while an activist who called for a boycott is now facing up to 12 years in prison on obviously faked charges. The day before the tournament started, critical media outlets like The Guardian and Radio France International were told they would not be allowed to enter Azerbaijan. As Amnesty International put it: “Azerbaijan wants to have these games in a criticism-free zone. It has already wiped out everybody who is critical of the government inside the country, and now it’s a closed-down state for international human rights groups as well.”

1The 2022 Qatar World Cup

The recent arrests and scandal surrounding FIFA, while no surprise to anyone familiar with the organization, have helped focus global attention on the growing scandal of the 2022 World Cup, which, for reasons that remain unclear, was awarded to the tiny and immensely wealthy nation of Qatar. While this raised some obvious logistical problems (the tournament will likely have to be played during the winter to avoid blistering heat) the real issue surrounds the treatment of the migrant workers building the World Cup’s infrastructure. In 2013, Qatar had a population of two million, of which just 10 percent were actually citizens of Qatar. Most of the rest were migrant workers from the Indian subcontinent. Lured by the promise of higher wages, the unfortunate workers find themselves effectively bound to one employer, forbidden to change jobs or even leave the country without their boss’s permission. They also can’t unionize. It should already be clear why this system of indentured servitude might be open to abuse. Not only are many workers forced to live in cramped, unsanitary conditions, but an investigation by The Guardian recently turned up a suspiciously high rate of death by “cardiac arrest” among Nepalese construction workers—likely the result of heatstroke caused by working long hours in the desert. Meanwhile, Qatar has actually detained human rights researchers investigating the situation. The additional publicity means some progress has been made, but there’s still a long way to go before conditions for Qatar’s migrant workers are anywhere near acceptable.