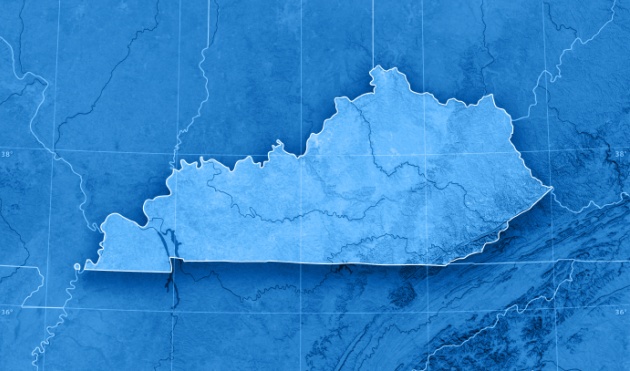

10 Kentuckians Accounted For 60 Percent of US Casualties

When the Kentucky Historical Society established a commission to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the War of 1812, they were paying tribute to a huge number of their own. Around 60 percent of US casualties during the war were from Kentucky, a statistic that sounds rather unlikely but is true. Kentucky suffered greater losses than any other state. At the time, the new state’s total population was only about 400,000, not much compared to other states like Virginia, which was home to one million people. More than 25,000 men from Kentucky served in the military and were stationed all over the US, making records extraordinarily difficult to track down. Some served for the requested 30-day enlistment period, some served much longer than that, and many were incorrectly recorded in the military’s record-keeping system, which too often relied on phonetic spellings for the names of their members. By the end of the war, the death toll was a number that seems surprisingly low—1,876 killed in battle (not counting the many more killed by disease), according to Kentucky’s official roster. Around 1,200 of those battle deaths were from Kentucky, serving as soldiers, sharpshooters, and spies in the fight to secure America’s freedom. Kentucky’s losses were so great that nine of its counties currently bear the names of men who fell in one of the most unlikely named battles of the war, the Battle of the River Raisin. While “Remember the Raisin” became one of the strangest battle cries ever, the names Simpson, Meade, McCracken, Hickman, Hart, Graves, Edmonson, Ballard, and Allan were given to state counties.

9 Laura SecordCanada’s Paul Revere

While the midnight ride of Paul Revere has entered into US mythology as a highly exaggerated story, Canada has their own version. Laura Ingersoll was born to a US family that had fought against the British only a short time before. Her heart had other ideas, though, and she eventually met and married British-allied James Secord. She ended up living with him in Queenston, Upper Canada. On June 21, 1813, a group of US soldiers showed up at their home and demanded food and lodging. While they were there, they discussed their plans, including where they were headed and exactly who their targets were. James, still recovering from wounds he’d sustained on the battlefield, was too weak to ride. Laura decided that she was going to warn the Americans’ target herself. So she started walking. It was 30 kilometers (20 mi) from her home to Beaver Dams. After hiking through swamps and bogs, she stumbled upon a group of Iroquois, who escorted her the rest of the way after she told them where she was going and who she had to warn of an impending attack. Her story was almost forgotten, as there’s no immediate mention of her in any of the contemporary records of the time. It was only in a letter from 1827 that Lieutenant FitzGibbon, the soldiers’ target, mentioned Laura as being responsible for the warning. And it wasn’t until decades after that—when she was 85 years old—that she was recognized for her bravery on those hot June days.

8 Hiram CronkThe Last Surviving Veteran

When it came to wartime heroics, Hiram Cronk missed the worst of the fighting. He enlisted in the military in 1814, during the heart of the war, and he was only 14 years old. As a part of the New York militia, he was stationed at Sackets Harbor. He arrived only after the worst of the fighting was over and spent 100 days in the military. Afterward, he led a pretty normal life. He got married, spent most of his life in New York, fathered seven children, helped to dig the Erie Canal, and worked as a shoemaker. He also stayed in touch with his fellow veterans, and in 1905, he died as the last surviving soldier from the War of 1812. Having reached the impressive age of 105, he was hailed as one of the final links between the post–Civil War US and a country that was still fighting to secure its freedom. Even though his service had been pretty uneventful, he was honored with an incredible military funeral and parade through New York City, which was recorded on video. Roughly 25,000 people showed up to pay their respects to the veteran as he was escorted to his final resting place in Cypress Hills Cemetery in Brooklyn. Among those who marched alongside him were members of the Washington Continental Guard, the New York City Mounted Police, and active members of the US Army.

7 Dolley Madison’s Red Dress

According to one of the war’s most popular stories, First Lady Dolley Madison was instrumental in saving some of the White House’s most priceless treasures from advancing soldiers. And while she might not have saved all the things she’s given credit for, it’s still pretty likely that she was instrumental in overseeing the evacuation of the White House and the rescue of some important pieces. One of those pieces is a little odd—the red velvet drapes that once decorated the Oval Drawing Room. In 1809, Congress approved a massive budget of $14,000 (that’s over $200,000 today) for redecorating the presidential residence. A minor crisis happened when, with silk in short supply, they had no choice but to go with heavy, red velvet curtains. The decorators were horrified, but Dolley Madison loved the look so much that the curtains were ultimately one of the things she saved from destruction by the British. She said as much in a letter that she wrote not long afterward, so we know she rescued them. It wasn’t until much later that a widowed Madison was forced to auction off her remaining belongings, including an iconic red dress that seemed to be made of an unlikely material. Eventually, it found its way to the Dolley Madison Memorial Association, which joined up with the Daughters of the American Revolution to try to match cloth samples from the red dress with samples of the velvet curtains. While microscopic examination revealed that the DAR’s cloth wasn’t the type of curtain that they thought it was, Madison’s red dress was the same kind of velvet that would have been used to make the real curtains. Did she use the White House curtains to fashion a dress? Evidence indicates that it’s highly likely, but we’re unlikely to ever know for sure.

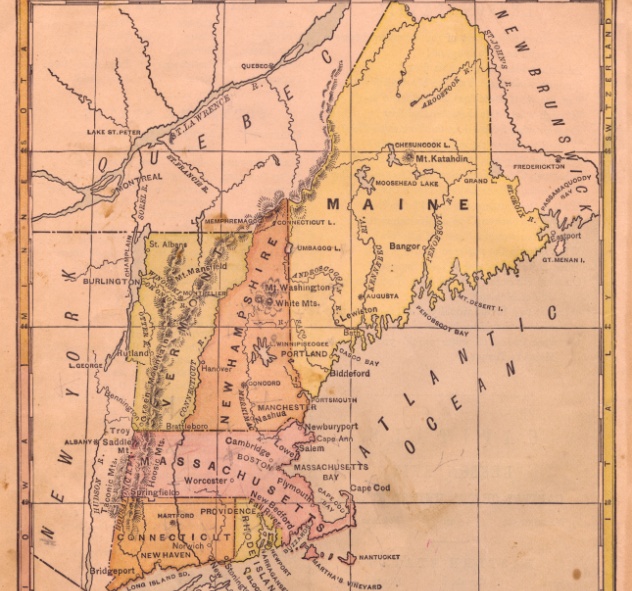

6 Machias Seal Island

The US and Canada still have an unresolved border dispute, and it dates back to the War of 1812. Machias Seal Island is less than 20 acres in area and sits about midway between Maine and New Brunswick. Technically, most border disputes were settled with the 1783 Treaty of Paris after the Revolutionary War, but by the time the War of 1812 came along, the British were occupying Maine. When the Treaty of Ghent was signed at the end of that war, it divided up most of the nearby islands and properties between the two nations. Not mentioned, however, was Machias Seal Island. Since it wasn’t specified just which nation should get the island, the British decided to go with a policy of “finders, keepers.” By 1832, they had built a lighthouse there, and aside from a brief period during World War I, it’s been solely occupied by Canadian forces, protected by the Canadian Coast Guard, and manned by Canadian lighthouse keepers. The island’s nationality sounds pretty straightforward, but in 2015, Canada and the US were still involved in what amounts to a sort of diplomatic shoving match over rights not only to the island, but to the well-stocked lobster fishing grounds around it. Disagreements over who has the right to fish the grounds have been going on for decades, with Canada pointing to a 1621 land grant to support their claim to the island and the US claiming that the 1783 treaty negates the first one. Weirdly, an opportunity arose to settle the argument in 1984, but it wasn’t taken. The issue was turned over to a court at The Hague that settled border disputes . . . but Machias Seal Island was left off the table, with neither country wanting to risk officially losing it.

5 Uncle Sam

“The Star-Spangled Banner” isn’t the only patriotic symbol that dates back to the War of 1812, even though it wasn’t until 1961 that Congress officially declared Sam Wilson of Troy, New York, as the man behind Uncle Sam. Born in Massachusetts in 1766, Wilson and his brother eventually moved to Troy, New York, where they became successful in the bricklaying and meatpacking industry. During the war, their company contracted with the government to supply rations to the troops. The barrels in which the military’s beef was packed were stamped with “U.S.” to mark them as part of the government contract, but those who handled the barrels often said that it was a reference to Sam Wilson’s real-life nickname, Uncle Sam. Though no one knows for sure, Wilson is believed to be the inspiration for the patriotic symbol. The earliest representations of Uncle Sam in connection with the United States date back to around 1813, and he took the place of another iconic representation of the country. Columbia (not Colombia), named for Christopher Columbus and taken from Latin words meaning “lands of Columbus,” was a female figure typically associated with the nation in its early days. She was eventually replaced by Uncle Sam and the Statue of Liberty. The use of figures like Columbia and Uncle Sam to symbolize an ideal or a nation is surprisingly ancient, dating back to the Roman era and finding increasing popularity throughout Renaissance Europe. While most people are probably more familiar with the name “Uncle Sam” than they are with the name of his inspiration, “Sam Wilson” pops up in another prominent place—as the real name of Marvel’s Falcon and new Captain America. It could easily be a coincidence, but if so, it’s a fitting one.

4 The Question Of Secession

After the American Revolution, England moved on to more wars closer to home, and with them came the need for more and more sailors to man their ships. When they started impressing US sailors into service on British ships, Thomas Jefferson partially solved the problem with an embargo that forbade trading between US ships and foreign countries. While that certainly kept soldiers out of foreign hands, it also ruined the country’s economy, particularly impacting New England. Suddenly, it wasn’t England that was the biggest problem; it was Washington. When Madison took over after Jefferson and declared war, he summoned New England militias to the South. Massachusetts said no, and in response, Madison sent no support to states that refused to support the war. New England was left to fend for itself and still bears the scars of British attack, as they burned ships, fired upon towns, and established an agreement with the Quakers that would leave them out of the conflict. The British continued to crack down on Northern trade, and New England politicians held their own meeting in Hartford, Connecticut, to discuss their options when it came to seceding from the United States. The top-secret meeting, now called the Hartford Convention, started on December 15, 1814, and members had some serious grievances. Those in power were largely Southerners, who had gotten where they were because of legislation that allowed slaves to count toward their population when it came to holding seats in Congress. Most of the expansion at the time was to the south and southwest, and the New England states already felt not only isolated, but as though they were bearing the worst of the impact from the war. They even got as far as drawing up a formal document that outlined the conditions that had to be met in order for them to remain a part of the country, and they were on their way to Washington, DC, to present those demands when the war ended. The end of the War of 1812 was seen as a big victory for the US, and the political mood changed in Madison’s favor. The New England politicians gave up and went home.

3 The Congreve Rockets

The Congreve rockets are the ones that inspired the line about “the rockets’ red glare” in “The Star-Spangled Banner,” and they were the brainchild of a British man named William Congreve. Until Congreve started working on them, rockets were used more as flares than weapons, but he saw huge possibilities in them, especially when it came to defending Britain against the then-imminent threat of a French invasion. Congreve’s tinkering increased the size and range of the rockets that were currently in use, but he couldn’t quite figure out how to aim them. By the time they were used at Fort McHenry, 10 years after their development began, they were still considered fairly experimental and were employed mostly against ships and forts. Aiming didn’t matter so much when you had a giant piece of wood as your target, and they would start fires wherever they landed. The rockets were too big to carry, so the British outfitted ships with them. The first ship to feature Congreve rockets sailed against the French, and the second was the Erebus, which was dispatched at Fort Henry. Even though they were used in huge numbers (between 600 and 700 were fired), the “red glare” was an exaggeration. The Erebus wasn’t even close enough to hit much, and at the end of the war, the death toll actually attributed to Congreve rockets was three. The rockets did, however, hit and destroy the Maryland farmhouse of a man named Henry Waller on August 28, 1814. At the end of the war, Waller sued the government for damages to his property. He won, thanks largely to his lawyer, Francis Scott Key.

2 Thomas Jefferson, The Library Of Congress, And Debt

After the British burned the capital and destroyed the Library of Congress, the largest private collection of books belonged to Thomas Jefferson. In 1815, he sold that collection to kick-start the Library of Congress yet again, giving the government 6,487 books for $23,950 (over $300,000 today). While it might have seemed like the perfect way to reboot the library in a win-win situation (the government got their books, and Jefferson could pay off some of his debts), not everyone wanted the collection. Some congressmen argued that the contents of the books might not be suitable for inclusion in a government collection. Some of the books were written in languages that other than English, leaving some bothered by the presence of books that not everyone could read. A bill needed to be passed to authorize the use of government funds to buy the library, and some Federalist congressmen argued that Jefferson was simply using the sale to get his supposed “infidel philosophy” into all corners of the government. The bill passed by only the narrowest of margins, and much of the money from the sale went to pay Jefferson’s creditors. William Short ended up with $10,500 of it (around $134,000 today) to settle some real estate debts. The last of Jefferson’s books left Monticello on May 8, 1815. When they got to the library, we’re guessing that the librarians were in for a bit of a surprise. Unlike most people, who tend to organize books alphabetically, Jefferson officially organized his by subject and unofficially organized them by size.

1 Black Refugees

When it came to strategy, the British struck at one of the subjects that formed a clear divide between the states—slavery. They offered slaves living in the US a choice: They could remain slaves, or they could join the British military and be given the right to settle as free men and women in British colonies after the war. Around 4,000 people took them up on the offer, and they ultimately became known as the Black Refugees. Most ended up settling in Trinidad, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and the West Indies after the war, making the War of 1812 the largest emancipation event in the country until the Civil War. Slave owners sent formal delegations to the British to complain about the loss of their “property.” Even free men who’d chosen to serve with the British Navy tried to talk some of the recruits out of their defection. Lack of manpower meant that there were a few options for black men to serve in the US Army, but the prospect of being captured by British troops and shipped off to Dartmoor Prison was less than favorable. While many distinguished themselves in combat on US ships and gained praise for their abilities in combat, the prospect of freedom was much, much sweeter. When the war ended, part of America’s demands included the return of its property either in body in or monetary reparations. The British absolutely refused on the grounds that any slave who made it to British soil was free, and British ships were British soil. They stayed free, too. The descendants of the ex-slaves who settled in Trinidad still call themselves “Merikans.” Read More: Twitter