10Oldest Pre-Alphabet Writing

During 2016, the archaeological site of Ad Putea delivered a historical surprise. Located in Northern Bulgaria, the fort used to be a Roman road station. The idea was to learn more about Ad Putea, but diggers unexpectedly came across an unknown settlement from the Copper Age underneath it. A few spadefuls into this era uncovered a ceramic fragment with markings. The 7,000-year-old shard appears to hold the world’s oldest pictographic writing, a picturesque way people recorded things important to them before the advent of the alphabet. The symbols include a swastika. Once part of a clay vessel, the writing on the prehistoric piece is two millennia older than those of ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt. Some Bulgarian experts even go as far as saying that Sumer’s famous linear writing and Egyptian hieroglyphs developed from a proto-writing that started in Northwest Bulgaria. The intriguing signs remain undeciphered.

9Mystery Meal

Another 2016 find saw archaeologists in Denmark pull a unique pot from a refuse pit. What made it one of a kind had nothing to do with the cauldron’s design or unusually preserved state. The content was strange. Usually, charcoaled plant matter remains behind in old cooking vessels. But during the cleaning process, instead, a light yellow crust popped up. It defied identification, and test results on the 3,000-year-old froth provided some clues but no solid answers. The substance appears to be a mix of bovine fat, oil, and sugar—a rare find as far as ancient meal traces go. Researchers can only tag its true identity once the future turns up something similar. However, one thing is certain. The attempt, possibly to make some cheese, met with such failure and a terrible smell that the cook chucked the pot away immediately.

8The Visigoth Takeover

In Northeastern Bulgaria, Visigoth pottery told a grim story. In the fourth century, Rome extended a helping hand when the Germanic tribes fled from the Huns. Allowing the refugees to settle near their fort, today known as Kovachevska Kale, was a decision the Romans would come to regret. Visigoths made distinctive ceramics, dark gray creations molded from high-quality clay. The sheer number discovered at the site told of a mass arrival of goths—ousting, in turn, the locals. A granary inside Kovachevska might’ve sparked its destruction. Food scarcity caused open warfare between the Visigoths and their Roman benefactors. Fire damage show the invaders won and torched the fort at one point. Afterward, the goths squatted between the ruins. Researchers made the conclusion based on 87 percent of Kovachevska pottery excavated since 1990 being gothic.

7The Israel Jug

During an archaeology class, Israeli schoolchildren found an extraordinary artifact. Pulled from the sands outside Tel Aviv, the jug is exactly what archaeologists expect from the Middle Bronze Age. An unusual decoration makes it unique and unlike anything found before in Israel. The figure of a person, done in exquisite detail, tops the jar. It’s unclear if the two parts were created by the same or different potters, but the upper portion of the vessel was adjusted to form the body of the figure. The limbs and face were then crafted onto this extension. The statue appears to sit and think very deeply about something, almost looking worried. The strange ceramic fusion measures 18 centimeters high and is nearly 4,000 years old. Found among weaponry, several other pottery items, and animal bones, researchers suspect the collection was included in an important individual’s funeral offerings.

6Plain Of Jars

In the 1930s, excavations began at one of Southeast Asia’s greatest mysteries. The Plain of Jars in Laos consists of about 100 locations stacked with pots. These are not your usual sort of pottery. Carved from stone, some weigh up to 10 tons. An unknown culture felt the need to drag the monster containers 8–10 kilometers from the quarry and arrange them in groups as large as 400. In contrast, single jars adorn other areas. The reason for this remains as missing as their original contents. During a new examination of Site 1, something was found that might finally provide answers. What turned out to be a veritable graveyard revealed 2,500-year-old human remains, some interred inside ceramic pots. Researchers are hoping that tests will reveal the ethnicity of this lost society and clarify if there is any connection with India’s own ancient jar fields.

5The Child Potters

An archaeologist, who is also a trained ceramist, discovered something previously unknown. Dr. Katarina Botwid was studying the neglected area of ancient pottery production, when she found that during the Bronze Age, children as young as nine could be skilled potters. Botwid came across juvenile fingerprints on ancient vessels, proving just who made them. As a ceramist herself, she estimated that it took about three years to raise these young artisans to expert level. Further assessment of the Bronze Age objects proved how the kids mastered a very difficult craft, something that surprised her. Even the most basic household item of the era sometimes demanded intense skill never before attributed to anyone but adults. She also believes that a much higher amount of pottery survived the firing techniques of the time, a remarkable 95 percent—40 percent more than generally accepted.

4Egyptian Pot Burials

The human remains found inside the Jar of Plains vessels were jumbled bones. Ancient Egypt potted the entire person. Citizens earmarked for such burials were thought to be the poor and the very young. The destitution theory developed when it was discovered that the domestically used pots were not specially made for the deceased. The “poor and young” angle doesn’t explain why certain sites contain only adults and in high-status tombs. Scholars remain divided about the meaning of it all. Surely, the afterworld-obsessed Egyptians had a reason for placing a corpse in a ceramic jar. Some experts feel that pots symbolized the womb and rebirth, while others cite a lack of archaeological evidence. For hundreds of years, pot burials remained a popular choice. Perhaps the durability of clay had something to do with it. Even today, they yield the best preserved bodies in ancient cemeteries.

3Infected Blood And Organs

Between 600–450 BC, a village in ancient Germany buried a special individual. At the time, he might not have felt all that special, considering that he had a bruised appearance and suffered bloody hemorrhaging of the gums, nose, stool, and urine. The rest of the villagers gave his organs and blood a strange send-off. He was interred in pottery vessels, and the gory receptacles were then laid to rest in a burial mound. By the time they were rediscovered, all that remained were dried shards. But ancient proteins still clung to them, and these identified the once-visceral contents and that the person had died from Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever. Carried by ticks and still killing people today, it’s the first discovery of the disease in the archaeological record. For the region, finding human blood and organs interred in pottery during the Bronze Age was also unique.

2The Peace Women

First found in Arizona during the 1930s, a ceramic collection became known as the “Salado Problem.” Spread across the territories of three native cultures of the American southwest, none could be identified as the source. The problem wasn’t just its origins but the purpose of the Salado pottery. All bore the same religious messages and symbols of fertility and cooperation. Researchers now believe that a new female religion, practiced during the 13th–15th centuries, produced the vessels. This was an extremely violent time, and northern refugees poured into the area. To prevent tensions between locals and newcomers from reaching the genocidal levels of the north, women banded together by participating in the same spiritual practices. The Salado religion was preserved only in ceramic creation. This was not a traditional male field, supporting the belief that it was the women who stabilized this multicultural society for centuries.

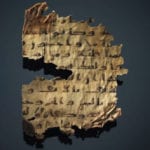

1Hidden Excellence

Greek pottery is known for the “black figure” depictions of daily life and battle scenes. The art form is particularly difficult to recreate. In an attempt to learn the mysterious artistic techniques, scientists specializing in conservation joined up with Stanford’s National Accelerator Laboratory. They zapped a Greek vase with X-ray fluorescence. Soon, it became clear why the work could never be authentically replicated. There had been too many assumptions. What was always thought to be a single coat of painting, the X-rays revealed to be a hidden world of chemical colors and more layers. The zinc additive credited for creating black during the firing process wasn’t even present, opening up another mystery—what happened during heating that caused the color? Nobody knows. Adding white was additional effort. The discovery finally gives Greek artisans back a level of excellence the art world never before suspected. Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages