Lazy, entitled millennials, selfies, slash fiction, a vacuous culture focused on nothing but remakes—every era has its problems, but those of the second decade in the 21st century seem especially odd. Forget eternal stuff like wars and terrorism; it’s the small things that show just how uniquely dumb our modern world is, right? Maybe not. Take a look at almost any symptom of our time here on Earth, and you’ll find that it has plenty of historical antecedents. As the saying goes, there’s nothing new under the Sun.

10 Millennials

They’re lazy, entitled narcissists who wouldn’t know an honest day’s work if it slapped them in the face. They care about nothing but selfies, Instagram, and other pointless wastes of time. They are millennials, and they’ve been around since the dawn of time. Although the word “millennials” is new to our vocabulary, the traits we associate with them aren’t. Fun as it might be to single out millennials as the downfall of Western civilization, everything that supposedly defines them has been said before about other generations. Repeatedly. In 1968, Life wrote an article claiming, “the phrase ‘to make a living’ could have absolutely no meaning” to baby boomers, whom it characterized as work-shy wimps. Fast forward a few decades, and baby boomers working for The New York Times wrote a similar article about Generation X, defining them as lazy and immature. Go back to ancient Greece, and you can even find Hesiod complaining that the younger generation “only care[s] about frivolous things.” While it’s doubtful that anyone in Hesiod’s day was spending time uploading selfies to Instagram, the general sentiment is identical. This doesn’t mean that millennials don’t have their own challenges and quirks, just that those complaining about them are simply seeing the same defects that the old have always seen in the young.

9 New Atheism

Atheism is the lack of belief in God and has been around for roughly forever. New Atheism, on the other hand, is a much more recent phenomenon. It’s the Richard Dawkins style of in-your-face confrontation on Twitter and deriding believers as gullible fools. It’s atheism as controversy, redefined from “lack of religion” to “anti-religion.” It’s also much older than many of us realize. In the 10th century, Syrian Muslim Abu al-Ala’ al-Maarri was so anti-religion that modern writers have called him “the Richard Dawkins of the Abbasid era.” Like New Atheists today, he was openly contemptuous of religion, publicly proclaiming that the world was split into two types of people—“those with brains, but no religion, and those with religion, but no brains.” He attracted a large group of followers, who were so openly mocking of Islam that they could have probably all got jobs working for Charlie Hebdo. Even earlier, Ibn al-Rawandi made a name for himself in ninth-century Baghdad by proclaiming Islamic tradition illogical, miracles hoaxes, and religion irrational. The two were basically the Dawkins and Hitchens of their times, provoking believers with direct challenges and public confrontations. Interestingly, neither attracted the ire of their pious countrymen, and both lived to a ripe old age.

8 Selfies

Nothing screams, “This is the end of culture!” like the modern obsession with selfies. People complain that they’re the ultimate expression of narcissism. Yet selfies aren’t some flash-in-the-pan phenomenon from the 21st century. They’ve been around basically as long as cameras. Thanks to the bulkiness of Victorian and Edwardian cameras, all selfies from the era had to be taken using mirrors. Other than that, though, they’re essentially identical. In 1914, Russian princess Anastasia Nikolaevna Romanova took what might be the first teenage selfie, posing with a bored expression. It’s the same shot you’ll see clogging up a million Instagram feeds around the world. Go back even further, and you’ll find people like Belgian artist Henri Evenepoel, who was using selfies as a means of artistic expression as early as 1898. They were also popular in wartime as a way for troops to send mementos to loved ones. Kodak selfies from World War I are considered valuable historical documents today.

7 Insane Fan Fiction

Think “fan fiction,” and you’ll probably picture misspelled tales from the grubbiest corners of the Internet featuring Kirk and Spock doing things that would make a seasoned porn star blush. Despite its popular association with geek culture, fan fiction has been around since before anyone knew what a geek was. At the start of the Common Era, one of the most popular sources of fan fiction was the Bible. The Gnostic gospels are essentially deranged rewrites of Christian tales by die-hard fans who didn’t want their favorite characters to die. In the 170s, for example, the Egyptian Gnostic Basilides penned a version of the crucifixion where Simon of Cyrene is mistaken for Jesus and crucified. Instead of dying, Jesus stands by the cross laughing at Simon. It’s not so different from modern fans torturously rewriting Harry Potter so that Dumbledore lives. Closer to our own time period, 1893 saw an explosion of a specific type of “fanfic” that most Internet users will recognize. That was the year that Arthur Conan Doyle killed off Sherlock Holmes. His fans reacted by writing and releasing their own mysteries for the detective to solve. That’s right—the Victorian era was just as awash with Sherlock fanfic as the modern Internet, only with fewer Benedict Cumberbatch gifs.

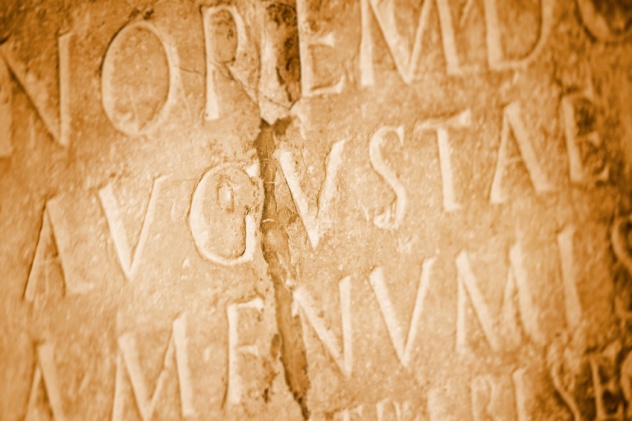

6 Social Media

Depending on your point of view, social media is either an incredible way to interact with fellow thinkers across the globe or an awful place where social justice warriors and alt-right types go to shout at each other. It certainly doesn’t seem very ancient. Tom Standage, former digital editor for The Economist, disagrees. According to him, social media has been around since Roman times. In his book, Writing on the Wall: Social Media: The First 2000 Years, Standage argues that Facebook and Twitter had precursors dating back centuries. In Vesuvius, for example, graffiti has been unearthed on ancient tavern walls that includes entire back-and-forth conversations. One example begins with a classic trolling status update: “Successus, a weaver, loves the innkeeper’s slave girl named Iris. She, however, does not love him. His rival wrote this. Bye, loser!” Underneath is the reply: “Envious one, why do you get in the way? Submit to a handsomer man who is being treated very wrongly and is darn good-looking.” Standage takes his argument further, pointing to ancient Roman abbreviations such as “SPD” (salutem plurimam dicit), which are not dissimilar from our “LOL” or “NSFW.” Whether or not you agree with him that this really constitutes social media, there’s no denying that these ancient communications were driven by the same impulses.

5 Annoying Advertisements

The Romans predated us with more than social media. Long before Don Draper was around, Romans were creating the ancient equivalent of annoying pop-up ads. During his reign, Caesar started something called the Acta Diurna—one of the earliest newspapers. Originally a propaganda organ for discrediting his foes, it soon evolved into something much more recognizable. Local interest stories were published alongside heartwarming tales of animals mourning after their dead owners . . . and alongside them were published advertisements. One surviving example comes courtesy of a guy named Maius, who stuck a “for rent” advert on the Acta promising “second story apartments fit for a king!” Since a copy of the Acta was published on wooden boards in the forum every day, wealthy Romans could even deploy a primitive form of AdBlock—sending a slave to copy the paper down but skip all the adverts. It wasn’t only in Rome that ancient advertisements surfaced. In Thebes, written adverts some 3,000 years old have been found offering rewards for runaway slaves.

4 Overpaid, Hedonistic Sports Stars

It’s a common grumble pf people who have to scrape by on less than a few million dollars each year. Modern sports stars are overpaid jerks who spend too much time getting drunk and appearing in tabloids and not enough time training. Today’s athletes have nothing on their ancient forebears, though. Sports stars of the ancient world were so wealthy and badly behaved that they make our guys look like thrifty saints. Chief of them all was Gaius Appuleius Diocles, a Roman chariot racer who lived in the 2nd century. Across 24 years, he competed in around 4,200 races, placing first or second in about half of them. His real specialty was winning the big money races. By the end of his career, he’d made himself the princely sum of 36 million Roman sesterces, enough to pay the salary of every single Roman in the army for two months. In today’s money, that works out to around $15 billion, making Diocles the highest-paid sportsman in history. More familiar to modern readers might be Milo of Croton, whose life was basically ancient tabloid fodder. A wrestler, he spent his spare time showing off his strength and getting insanely drunk in public. It was said he could drink 8 quarts of wine in one sitting, the sort of sentence that usually precedes the words “before dying of an overdose.” Interestingly, Milo’s eventual death was even crazier. As an old man, he supposedly tried to show off by splitting a tree with his bare hands, but he became stuck and was—somehow—eaten by wolves.

3 Cash Grabs And Unimaginative Sequels

Calling Hollywood unoriginal today is itself pretty unoriginal. Since the early 2000s, people have been complaining that modern entertainment is risk-averse, preferring cash grabs and bad sequels to fresh ideas. Guess what: That was as true at the birth of cinema as it is now. The first feature-length blockbuster was D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation. Released in 1915, it’s notorious today for featuring the Ku Klux Klan as the good guys. It made a ton of money on release, and the studio immediately cashed in by green-lighting a sequel. Known as Fall of a Nation, the sequel landed in 1916 and was by all accounts a massive disappointment. Although it still featured some “good” Klansmen, it also focused on a consortium of evil Europeans taking over the US and their defeat at the hands of a pro-war congressman. The New York Times called it propaganda and stated that it was “sometimes preposterous.” Fall of a Nation is now thought to be lost forever. Lest you think it was just early Hollywood that was unimaginative, terrible book sequels were a real fact of life in the 19th century. Only months after H.G. Wells blew minds with his War of the Worlds, Garrett P. Serviss had released an unauthorized sequel that featured Thomas Edison flying to the red planet to kick Martian butt. Earlier still, an unauthorized sequel to Part One of Don Quixote so outraged Cervantes that it probably contributed to him finishing his masterpiece.

2 Modern Disney Stories

Most of the Disney stories that kids watch today are old. Frozen is based on a Hans Christian Andersen tale; Tangled is just Rapunzel from the Brothers Grimm. But many of us might not know how old some of these fairy tales really are. Recent evidence has suggested that some of the best-known don’t date from the 1500s. They could be up to 5,000 years old. In a study published in Royal Society Open Science, a group of folklorists and anthropologists traced the ancestry of tales appearing in 50 Indo-European languages. They found that about a quarter of them had extremely ancient roots. “Jack and the Beanstalk,” for example, was traced back 5,000 years to the split between Western and Eastern Indo-European languages. Others, such as Beauty and the Beast, could be up to 1,000 years older than that. To put that in perspective, if Moses had spent his exile in Europe, there’s a chance that he would have heard the same stories as you growing up. Amazingly, these aren’t even the oldest tales the study identified. While not all folklorists agree with their assessment, the authors decided that one tale known as “The Smith and the Devil” likely originated in the Bronze Age. If Disney were to make a film of that, it would be the longest page-to-screen waiting time in human history.

1 Listicles

As anyone who writes for a list-based website can tell you, journalists sure love to hate on listicles (list-form Internet articles). The Internet is awash with “hilariously” ironic articles in serious publications, featuring titles like “35 reasons why I hate lists” and “8 Reasons to Avoid Listicles.” The arguments are always the same: Humans invented writing. (“Great!”) Then online sites started writing lists. (“Boo!”) It’s as if most people think that nobody employed the list format prior to 2013, and those who did have done so only to annoy the real journalists. As you’ve probably guessed from the rest of this numerically ordered article, that isn’t really true. Listicles have been around as long as human beings have liked to rank things. One example from the 1800s is “The Fate of the Apostles,” which Smithsonian Magazine has called a 19th-century “viral sensation.” It depicted the way each of Jesus’s apostles died in chronological order and was reprinted around 110 times, which in today’s terms would be like finding out that your list has been linked on The Guardian, CNN, BBC, and The New York Times and has been retweeted by everyone in Hollywood. At least 650 other articles in the era had a similar reception, including a whole load of listicles. Then there are the famous list-writers. Leonardo da Vinci and Benjamin Franklin were compulsive list-makers. Writer Umberto Eco claimed that you could find examples of artistic list-writing in the works of Homer and Thomas Mann. In short, compulsively reading lists might be a basic part of human nature. As Eco said: “The list doesn’t destroy culture; it creates it. Wherever you look in cultural history, you will find lists.” It’s official, folks: One of Italy’s greatest 20th-century authors thinks Listverse is the pinnacle of culture.