Most of the people who entered asylums never left. They remained nameless, faceless sufferers whose stories were forgotten. There are some, though, who either lived to tell their tales or whose memories survive in the letters they wrote.

10 Herman Charles Merivale

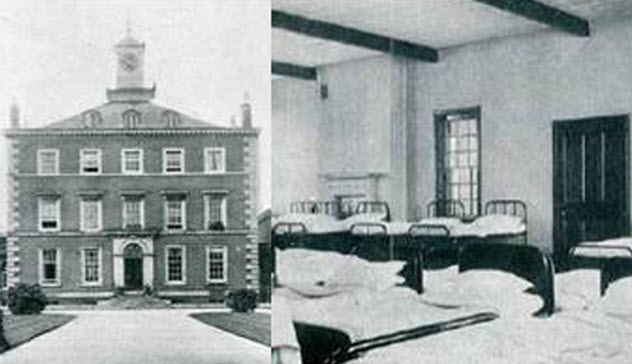

Barrister Herman Charles Merivale’s account of his confinement in England’s Ticehurst House Hospital is a rare one. In 1875, he found himself committed with no memory of how he had ended up in the asylum. He wrote My Experiences in a Lunatic Asylum, by a Sane Patient and gave a rational, firsthand account of life there. On the one hand, he described a “delightful sanitary resort” where he was taken on regular outings, attended chapel, and enjoyed performances by traveling entertainers. On the other hand, he wrote of attendants who slept in his room when needed, the screaming and crying of other patients, and regular visits from Death. Released after a few months, Merivale was readmitted after trying to strangle an acquaintance. He was released again in 1877, although his file notes that he had “not improved.”

9 Clarissa Caldwell Lathrop

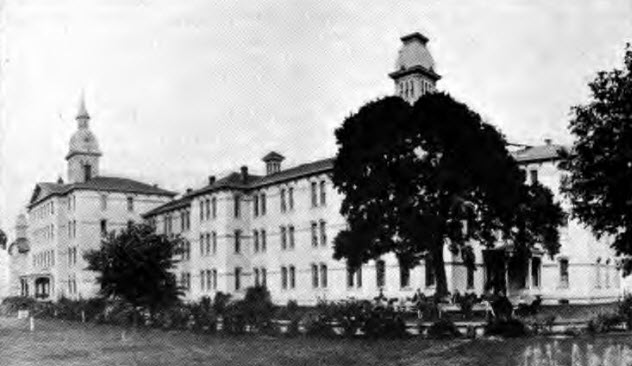

Clarissa Caldwell Lathrop wrote A Secret Institution, which was published in 1890. The book tells of her life in an asylum and the circumstances that led her there. After a former fiance left her for life—and a wife—in New York City, Lathrop struggled to move on despite her ex-fiance’s continued efforts to contact her. Years later, she received word of a wealthy city couple embroiled in disputes over divorce and infidelity, whom she suspected to be her former love. About the same time, a stranger showed up on her doorstep looking for board. Lathrop fell gravely ill after taking her in. Although doctors were unsure of the cause, Lathrop became convinced that the mysterious boarder was the estranged wife of her former paramour, come to poison her. Lathrop writes of finding mysterious powders in her drinks and on her hairbrush and took her concerns to her family doctor and to her mother. The doctors committed her to Utica Asylum, where she fought tirelessly for an appeal and inmates’ rights.

8 Reverend Hiram Chase

Committed to the New York State Asylum at Utica from 1863 to 1865, the Reverend Hiram Chase wrote Two Years and Four Months in a Lunatic Asylum about his bad experiences there, including a bizarre practice called institutional tourism. For real change to happen, Chase believed that the public needed to be aware of what went on behind closed doors. However, he did not believe that the public needed to come inside to gawk at the patients—which was exactly what was done. Chase repeatedly asked to live in an area of the asylum that was never a part of the public tours. But he was turned down. He wrote of the rules patients were given for public visits, the punishments for breaking them, and the idea that only the “better behaved” patients were seen by visitors.

7 James Doran

James Doran’s cause of death was internal injuries that included seven broken ribs but with no bruising or visible marks of abuse. A jury ruled that the death was from natural causes. Doran died on the day that he was transferred to Prestwich Asylum, which earned him an article in the June 13, 1870, edition of the Liverpool Daily Post along with an official inquiry. His brother testified that Doran was committed after becoming suddenly insane, demonstrating violent behavior that had escalated for two months. He was first confined at the Marland Workhouse in Rochdale, where attendants claimed that his bruises were self-inflicted. No one was ever found guilty of mistreating Doran, but the inquiry into his death did shed light on the practice of breaking the bones of paralytic patients in the misguided belief that it was the only way to quiet someone who was screaming.

6 ‘James R. Robblett’

On June 14, 1936, The Oregonian ran the story of “James R. Robblett” (not his real name), a patient at the Oregon State Hospital. At the time, terms like “insane” and “bughouse” were falling out of fashion. According to doctors, Robblett had “insight,” the rare ability to speak coherently about what ailed him. He admitted that he hadn’t entered the asylum freely but was committed because of a combination of working too hard, not getting enough exercise, living in a claustrophobic space, and having a nervous breakdown. The first thing that struck him was a complete inability to tell the difference between the patients and the staff. First confined to Ward C, he also talked about his time in the observation ward with patients of all sorts, even those who had been infected with malaria to cure their syphilis.

5 Mary Meller

Mary Meller, 27, was pregnant with her fifth child when she was tried for the attempted murder of a lodger. After hitting the woman and trying to slit her throat, Meller went before the court at the Old Bailey. With the help of a doctor’s testimony and claims that she had previously tried to commit suicide, Meller was found not guilty by insanity. She was committed to Broadmoor in 1868. After she gave birth to a baby boy that was passed to the care of her husband, the staff noted a remarkable change in her behavior. It turned out that the difference was sobriety. Meller later confessed that she had been drunk when she attacked the lodger. Even though she was released into her husband’s care, she soon relapsed. Committed again after being chased through the London streets by an angry mob (for an unspecified crime), she ultimately died in 1878.

4 Gerald

In 1901, Gerald was admitted to St. Ita’s Hospital in Portrane, Ireland. In 1912, he wrote a heartbreaking letter to his father asking for his freedom. Gerald reminded his father of his promise—that if Gerald stayed in the asylum, he would enjoy privilege and status unlike any other patient there. After refusing the offer, Gerald was committed anyway. In spite of the doctor’s belief that Gerald could return to his family and live a perfectly happy life, his father simply ignored all attempts to release his son. It isn’t clear why Gerald was committed, aside from his mention of the temper and grief that had since disappeared. He wrote, “Hopes of my discharge I have consigned to oblivion. I see the years before me, and my soul shrinks at the appalling prospect.” He died in 1949 with no family present.

3 Ralph Holmes

Ralph Holmes was the son of Bayard Holmes (pictured), a homeopath and bacteriologist who crusaded for changes to health care in the face of increasing industrialization. In 1905, Ralph was diagnosed with schizophrenia. At first, he was committed to a private sanitarium and treated with an amount of medication that his father found unfathomable. After visiting more asylums, Bayard saw that they were more of a problem than a cure and devoted his life to finding a cure for his son’s illness. As Ralph worsened, his father developed the idea that schizophrenia was ultimately caused by a buildup of a toxin in the intestines. His cure was to remove the appendix and perform routine maintenance to keep the gut toxin-free. His first subject was Ralph, who died from complications four days after the operation. While his father continued his quest, most of his writing makes no mention of his son.

2 G.

Identified only as G., this patient was admitted in 1892 to the Devon County Lunatic Asylum after threatening his wife with a hot poker and consequently being deemed a danger to society. Although G. had shown no previous signs of mental illness, his mother had been deemed insane. Therefore, G. was believed to be showing signs of a latent but inherited illness. After being admitted, he was diagnosed with melancholy. Quiet and listless, he showed no signs of violence aside from the incident described by his wife. After three months, there was no change in his condition. His file was moved to the “Chronic Casebook,” which was filled with patients unlikely to be released. He died in 1918 after 26 years in the asylum. The cause of death was dysentery.

1 Henry Jr. And Adolph Cotton

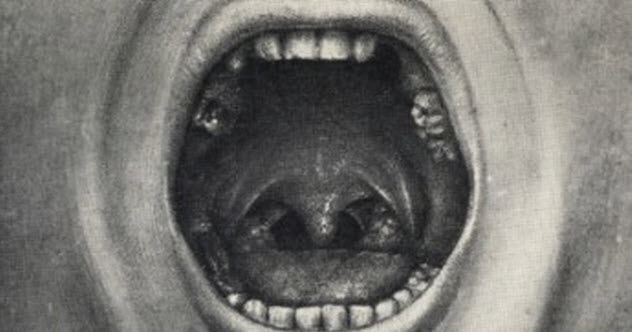

Having rejected ideas of inherited mental illness, Dr. Henry Cotton of the New Jersey State Hospital in Trenton started looking elsewhere for the cause. His theory was that toxins built up in various parts of the body and caused mental difficulties. Remove the body part, and you would remove the problem. Over the next few years, he removed thousands of teeth and tonsils before moving on to spleens, thyroids, reproductive organs, and colons. He also operated on some perfectly healthy patients as a preventative measure. Those patients included Cotton’s wife and his sons, Henry Jr. and Adolph. Cotton not only pulled all of his sons’ teeth, but he also removed part of his younger son’s colon. Both sons committed suicide in middle age.

+Further Reading

If you need more tales from bedlam, fear not: there are plenty more lists where this came from! 10 Crazy Facts From Bedlam, History’s Most Notorious Asylum Top 10 Notable Residents of Broadmoor Hospital 10 Brutal Accounts Of Torture In Old Insane Asylums 10 Unsettling Mysteries From Asylums And Institutions 10 Horrifying Hospitals You Never Want To Stay In Read More: Twitter