From the moment Admiral George Dewey sailed into Manila Bay and defeated the Spanish fleet on May 1, 1898, the US looked on the Philippines covetously for new markets and investment opportunities. America also wanted to block other European powers, particularly Germany and Britain, from gaining control of the islands. The ensuing conflict took the lives of 220,000 Filipinos who stood in the way of US ambitions.

10 Total Ignorance

Never had America been so ignorant about a target. Humorist Finley Peter Dunne wisecracked that Americans couldn’t tell whether the Philippines were islands or canned goods. President William McKinley himself admitted that he “could not have told where those darned islands were within 2,000 miles.” Nevertheless, he later decided, after much soul-searching and prayer, that America had no choice but to take in the Filipinos, “uplift them, and civilize and Christianize them.” This uninformed justification for conquest overlooked the fact that Filipinos already had more than 300 years of European civilization behind them courtesy of Spain and were already Christians. The imperialist senator Albert Beveridge echoed McKinley by affirming America’s duty to impose its rule and way of life upon a “barbarous race.” British poet Rudyard Kipling encouraged the US to pursue its empire and take up the “white man’s burden” to care for “your new-caught sullen peoples/half devil and half child.” On September 22, 1898, Don Felipe Agoncillo arrived in San Francisco on a mission to convince the US of his people’s sincere aspirations for independence. San Franciscans had been so misled by newspapers describing Filipinos as uncouth, monkey-like, and uncivilized, that they fully expected a tribal chief in a loincloth to walk down the gangplank. They were taken aback when Agoncillo appeared in an elegant European suit and top hat. Agoncillo proceeded to Washington, where he pleaded his cause in vain, unable to steer America from its predatory course. In the Treaty of Paris on December 10, 1898, Spain ceded the Philippines to the US for $20 million. The ultra-conservative Speaker of the House, Thomas Reed, remarked ominously, “We have bought 10 million Malays at two dollars a head unpicked, and nobody knows what it will cost to pick them.” The answer would not be long in coming.

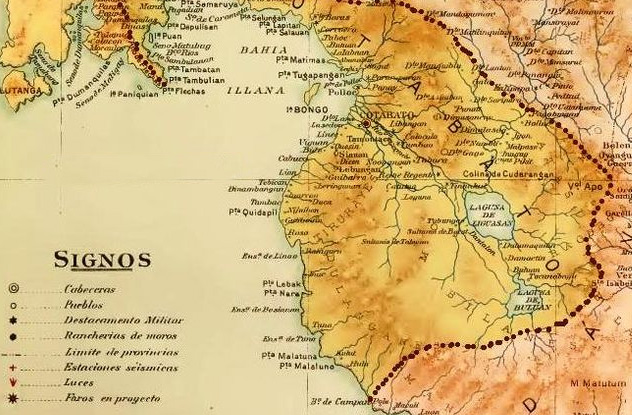

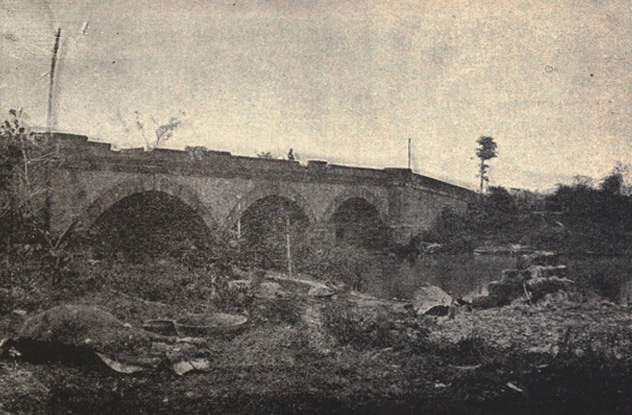

9 The San Juan Bridge Incident

Initially, Filipinos were led to believe that the Americans came as allies against the Spanish, whom they had been fighting for two years. Aguinaldo had told his people, “Where you see the American flag flying, there assemble in numbers, they are our redeemers!” He proclaimed Philippine independence on June 12, 1898. An American artillery colonel, M.L. Johnson, witnessed the proceedings. But having ousted the Spaniards, the US Army stayed on. As more troops landed, the Americans’ real intentions became clear. The first sign that all was not well was when the Americans prevented Filipinos from entering Manila. A system of opposing trenches grew up around the city, separating the two armies. Mounting territory violations by both sides heightened tensions. On the night of February 4, 1899, trigger-happy Nebraska volunteer William Grayson and his companion Orville Miller shot and killed two unarmed Filipino soldiers trying to cross to American lines near the San Juan Bridge. The Filipinos fired back in response. Aguinaldo frantically sought to halt the escalation, but the American commander, General Elwell Otis, jumped at the chance to commence hostilities. The “fighting, having begun, must go on to the grim end,” Otis said. The Americans, having betrayed the Filipinos’ trust, plunged forward into their trenches. The war was on.

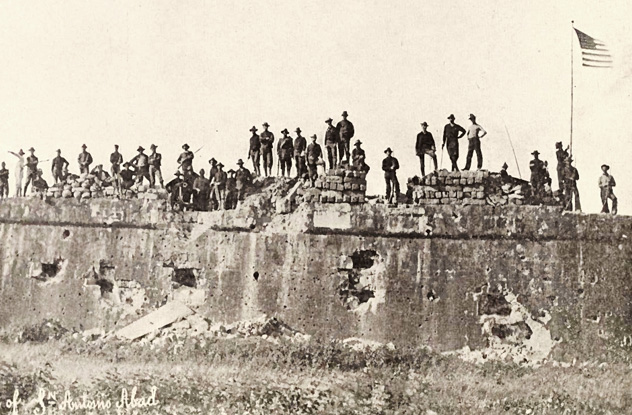

8‘Murderous Butchery’The Battle Of Manila

As the Americans swarmed over the Filipino trenches around Manila, they used their superior firepower to inflict horrendous casualties on the locals. Admiral George Dewey turned his fleet’s naval guns on the Filipinos, prompting an English resident of Manila to say, “This is not war—it is simple massacre and murderous butchery.” The Americans gunned down 700 Filipinos who tried to flee across the Pasig River. One US soldier exulted that “picking off n—rs in the water” was “more fun than a turkey shoot.” But not every American soldier had a picnic. Sergeant Arthur Vickers of the First Nebraska Regiment said, “I’m not afraid, and am always ready to do my duty, but I would like someone to tell me what we are fighting for.” As Filipino dead piled up, another soldier reflected, “We came here to help, not to slaughter, these natives. I cannot see that we are fighting for any principle now.” Similar introspection was far from General Otis’s mind as his forces rolled over the suburbs, burning, plundering, and looting private homes. Aguinaldo’s call for a ceasefire and peace talks was rebuffed. Otis, overoptimistic, prematurely informed Washington that the “insurgent” army was disintegrating. He couldn’t be more wrong. The Filipinos had been pushed back, but they were not finished. And the cost of picking Malays was already far from cheap: 57 US troops dead and 215 wounded against 1,000–3,000 natives killed.

7 Civilizing With A Krag

Many blatantly racist US troops referred to the natives with slurs such as “black devils” or “gugus.” One wrote back home that they had come “to blow every n—r to n—r heaven.” The fighting would continue “until the n—rs are killed off like the Indians.” They sang a ditty while they marched: “Damn, damn, damn the Filipino Pock-marked khadiak ladrone! Underneath our starry flag Civilize him with a Krag And return us to our own beloved home.” “Krag” referred to the standard-issue Krag-Jorgensen rifle. With such contempt, the Army had no qualms using the “dum dum,” or expanding bullets, on the Filipinos. The Hague Peace Conference had outlawed the ammunition against the opposition of the Americans and the British. The conflict increased in savagery as Aguinaldo retreated farther into the mountains and switched to guerrilla tactics. The Americans realized that they not only had to deal with the enemy’s regular army but also with the local population’s ambushes and hit-and-run attacks. American frustration mounted at their inability to nail down the enemy. When a reporter commented that “Filipinos are brave,” an exasperated General Loyd Wheaton pounded his table and thundered, “Brave? Brave? Damn ’em, they won’t stand up to be shot!” Numerous atrocities were committed to smoke out the guerrillas. Burning villages, killing non-combatants, and the “water cure” became routine. This “water cure” consisted of forcibly filling the victim with gallons of water then kneeling on the bloated stomach to force the water out. Short of firearms, Filipinos commonly used bolos, a machete-like weapon that mutilated victims. This confirmed, to the Americans at least, that the enemy were indeed treacherous barbarians of the lowest kind, justifying ruthless methods of dealing with them. General Arthur MacArthur called US action “the most legitimate and humane war ever conducted on the face of the Earth.”

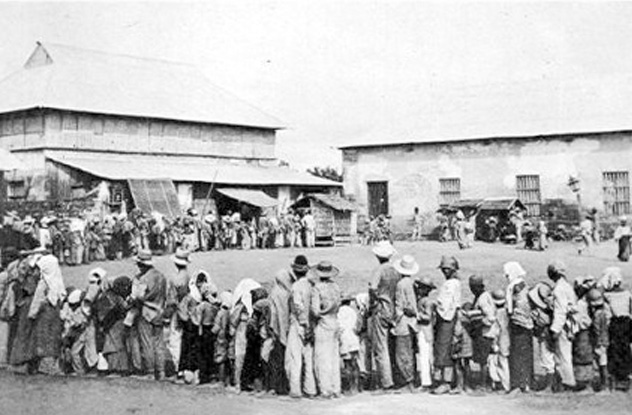

6 Concentration Camps

The US went to war against Spain partly in protest against their policy of “reconcentration” in Cuba. As the term implies, Spain herded civilians into concentration camps, where many died under unspeakable conditions. Americans then implemented the same cruel and inhumane strategy in the Philippines. Reconcentration aimed to flush guerrillas out by cutting them off from local aid and provisions. Non-combatants were forcibly removed from their villages and sources of livelihood. The camps they were confined in were usually overcrowded, lacking in food, water, and proper sanitation. The filth brought deadly diseases like cholera, wiping out many. The area around the camp was designated a free-fire zone called a “dead line.” Anyone found outside the camp was deemed a guerrilla and shot. The surrounding area was also systematically destroyed as part of a scorched-earth policy. In the campaign against the guerrillas in Batangas province, General J. Franklin Bell gave the people two weeks to get themselves into detention. Outside the camps, crops were destroyed, wells were poisoned, and farm animals were slaughtered. Bell spelled out his intentions very clearly: “All consideration and regard for the inhabitants of this place cease from the day I become commander.” The people of Batangas were to be made to “want peace and want it badly.” The death of an American soldier was punished by taking a native prisoner by lot and executing him. Bell’s campaign of terror killed 100,000 of the province’s population.

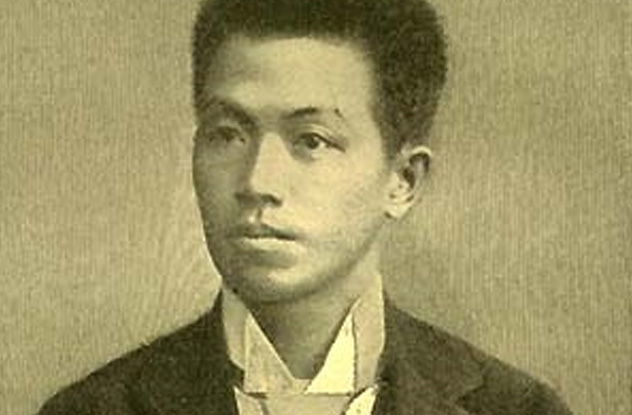

5 The Battle Of Tirad Pass

The 24-year-old boy general of the Filipinos, Gregorio del Pilar fought his last battle defending a mountain pass to let others escape Americans in pursuit. It has been compared to the heroic last stand of Leonidas and his Spartans, and Tirad Pass has become the Philippines’ Thermopylae. The pass is 1,350 meters (4,441 ft) above sea level, and a war correspondent dubbed the action “The Battle Above The Clouds.” On the morning of December 2, 1899, a force of 300 Americans under Major Peyton March found their way blocked by del Pilar and his 60 men near the side of a cliff. As the Americans besieged the pass, they could see del Pilar astride his white horse, alternately praising and cursing his men as the battle progressed. In such difficult terrain, Major March’s Texans couldn’t see the enemy’s exact location or how to reach it. It was then that their Igorot (a mountain tribe) guide showed them a secret trail to the top of the mountain. Thus betrayed, del Pilar was driven from his first entrenchment. He retreated to the second defensive line, his men being cut to pieces around him. Only after every man in the trench was dead did the young general spur his horse up the winding trail. A sharpshooter took aim, and del Pilar was hit in the neck. The jubilant Americans rushed up the mountain to find the boy general dead. The soldiers looted his body—diary, gold locket, shoes, clothes, and all. Only eight Filipinos escaped alive. Del Pilar’s body lay exposed for days until Lt. Dennis Quinlan, out of respect for a fellow officer, gave it a military burial and a tombstone inscribed “An Officer and A Gentleman.”

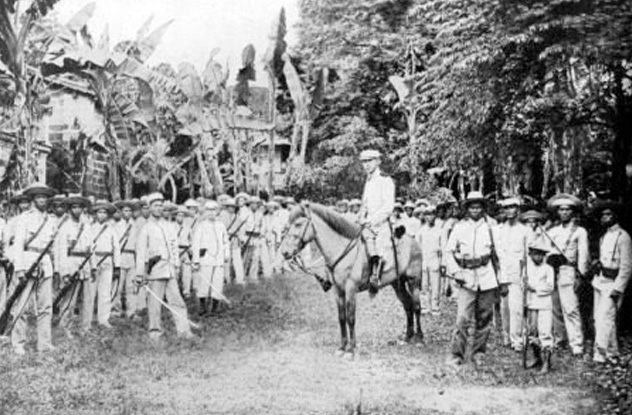

4 The Capture Of Aguinaldo

The President of the First Philippine Republic, General Emilio Aguinaldo, had been on the run since November 1899. Dodging the pursuing Americans meant enduring the hardships of traversing the forbidding jungles, crossing creeks and swamps infested with reptiles and leeches. The president and his small group of companions sometimes went for days without food or water or subsisted on whatever they could pick along the way. Del Pilar’s sacrifice let them reach the safety of the village of Palanan on the Pacific coast of Luzon. The Americans lost track of Aguinaldo until they intercepted his letters asking for reinforcements at Palanan. This gave General Frederick Funston the idea of penetrating Aguinaldo’s camp by trickery. He recruited 80 members of an ethnic group loyal to the Americans (the Macabebes) and disguised them as the long-awaited “reinforcements.” Funston forged the signature of a Filipino general on a letter authorizing their dispatch to Palanan. With four other Filipinos who had switched sides, a Spanish interpreter, and four other Americans, Funston avoided spies and hostile mountain jungles by landing a gunboat on a beach nine days’ march from Aguinaldo’s hideout. On March 23, 1901, the Macabebes gained entry to the camp, posing as the reinforcements with five supposed American prisoners. Aguinaldo welcomed them joyously. At a signal, the Macabebes opened fire on the camp guards, while Aguinaldo was grabbed from behind. A colonel tried to shield him from the bullets. Aguinaldo himself whipped out a pistol, determined not to be caught alive, but a follower held him back. General Funston stepped forward and arrested Aguinaldo in the name of the United States. Aguinaldo was taken to Manila, where he finally took the oath of allegiance to the United States. On April 19, he appealed to the people to do the same, saying, “Enough of blood, enough of tears and desolation! By acknowledging the sovereignty of the United States . . . I believe I am serving thee, my beloved country. May happiness be thine!”

3 The Massacre Of Balangiga

Captain Thomas Connell was of a different breed from his fellow soldiers. He was friendly to the Filipinos and sincerely worked to gain their trust so they might accept American colonialism. Connell was also a Catholic, as were the majority of the natives. In August 1901, Connell and his Company C arrived in Balangiga on the coast of Samar Island. He reminded his men to maintain good relations with the townspeople, forbidding them to use slurs. When three young girls complained that they had been raped by the soldiers, Connell furiously ordered that anyone found guilty of molesting or even touching native women be court-martialed and shot. In a fateful decision, Connell also ordered that the men should carry no weapons except when on sentry duty. The provocation for the events that followed is still in dispute. What we do know is that on September 27, 1901, the Americans thought they saw native women carrying an unusually large number of coffins into a church. The Filipinos said the coffins contained bodies of children who had died in a cholera epidemic. There were children in the coffins, sure enough—but they were playing dead. Underneath them, the coffins were filled with bolo knives. And because of the order against touching women, the mourners had not been searched. Had they been, the Americans would have discovered that they were actually men underneath the dresses. When the bugle sounded for breakfast, the unarmed Americans entered the mess hall. The church bells clanged. At that signal, the Filipinos charged with their bolos. The Americans couldn’t reach for their guns in time, and many were hacked to pieces at the breakfast table. Company C desperately fought off the attackers with cooking utensils, steak knives, and chairs. Connell was in his room reading his prayer book when the Filipinos burst in. He managed to leap out the window, but he was cornered in the street and decapitated. When the attack was over, only 26 of the 74-man unit were alive, 22 of them seriously injured. They escaped to a nearby town garrisoned by another US company. The news of the massacre shocked America. “The slaughter is the most overwhelming defeat that American arms have encountered in the Orient,” reported the Evening World. “So sudden and unexpected was the onslaught and so well hemmed-in were they by the barbarians that the spot became a slaughter-pen for the little band of Americans.” The massacre reinforced the impression that Filipinos were brute savages who needed “bayonet rule” to be pacified. Balangiga was eventually retaken, and the church bells that rang in the attack were taken down. Two are now on display at Warren AFB in Cheyenne, Wyoming. Despite pleas to American authorities, most recently to President Barack Obama, the US shows no intention of returning their trophies of war.

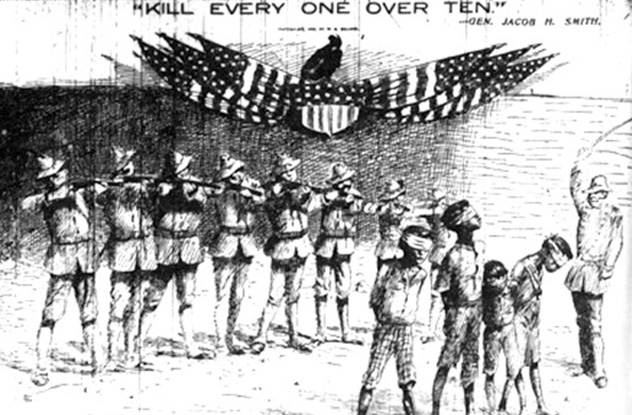

2 The Pacification Of Samar

General Jacob H. Smith was no stranger to the inhumanity of war. As a cavalryman, he’d witnessed an earlier massacre of 300 Sioux at Wounded Knee, South Dakota by the US Army. Now, the shoe was on the other foot, and in retaliation for Balangiga, Gen. Smith vowed to make Samar a “howling wilderness.” He would forever be remembered as “Howling Jake.” Smith issued his orders to Major Littleton Waller: “I want no prisoners. I wish you to kill and burn. The more you kill and burn, the better you will please me. I want all persons killed who are capable of bearing arms in actual hostilities against the United States.” When Waller inquired on the minimum age for those he deemed “capable of bearing arms,” Smith replied “10 years.” For the next five months, his men rampaged throughout Samar. Food and trade to the island were cut off to starve the enemy to submission. All the inhabitants were regarded as hostile until they proved otherwise, such as by providing information on the guerrillas. Even that was no guarantee—Major Waller ordered the execution of his native guides for allegedly not sharing food with famished Americans after a long march. In the end, Samar had 50,000 fewer people. Only the restraint of most of Smith’s subordinates prevented the campaign from becoming full-blown genocide. News of the atrocities reached an American public already growing tired of the war. Smith’s infamous order was editorialized by the New York Journal with a cartoon of Filipino children with their backs to a US firing squad. “Kill Every One Over Ten,” reads the caption. “Criminals Because They Were Born Ten Years Before We Took The Philippines.” Surrounded by American flags, a vulture (instead of a bald eagle) presides over the scene. In response to the outcry, Howling Jake was hauled in to be court-martialed. He was convicted and disgraced, as were his fellow officers, who hailed him as a hero. Major Waller was acquitted of killing his guides, but the affair cost him the leadership of the Marine Corps. His opponents dubbed him “The Butcher of Samar.”

1 The Bandit President

President Theodore Roosevelt formally announced the end of the war in 1902. But like George W. Bush’s proclamation of “Mission Accomplished” in Iraq more than a century later, it was woefully premature. Bands of revolutionaries continued to plague the Americans as they settled down to rule their colony. One of these was a colorful character named Macario Sakay. A former actor, Sakay was a dashing and romantic figure off-stage as well. He defied the Americans even after being released on amnesty in 1902, naming himself President of the Tagalog Republic, Aguinaldo’s successor. Sakay controlled the provinces around Manila, and the Republic had its own flag, constitution, and government. Most of all, it had the support of many people in the region. Sakay and his lieutenants wore their hair long, as a symbol of the length of their struggle. Sakay also wore a vest with religious images and Latin phrases that was believed to make him bulletproof. He set up headquarters near the mystical Mt. Banahaw, protected by members of a millenarian sect. American authorities exploited the enemy’s unshorn locks to portray them as bandits and common criminals. They passed the Brigandage Act declaring resistance to US rule a capital crime. But far from being a disorganized bandit gang, Sakay’s troops were disciplined, even boasting an engineer and medical corps in full uniform. Three thousand government troops were sent to engage them, and another campaign of reconcentration was launched in the provinces of the Tagalog Republic. Sakay was finally lured into a trap. He was told that the Americans planned to set up a national assembly that would include Filipinos, and as soon as the natives were ready for self-government, the US would grant them independence. He would be amnestied if he ceased his resistance movement. Sakay and his top aides journeyed to Manila with a safe-conduct assurance from the authorities, acclaimed along the way by admiring crowds. At a town fiesta, Sakay and his officers were arrested, thrown into prison, and charged under the Brigandage Act. Despite a huge demonstration that pleaded with the governor-general for clemency, Sakay was hanged on September 13, 1907. American propaganda had been so thorough and effective that even today, some Filipinos still dismiss Macario Sakay as a bandit rather than a genuine freedom fighter. For a long time, the image of the long-haired outlaw was a common stereotype. Sakay has no major street named after him in the country he fought for. He is a forgotten figure in a forgotten war.

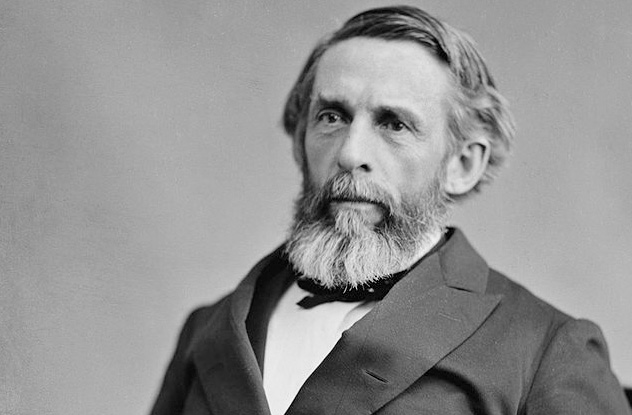

+ The Anti-Imperialist League

Many thinking Americans opposed the annexation of the Philippines because it violated the principles upon which the United States was founded, particularly the right of self-determination. They formed the Anti-Imperialist League in Boston in June 1898 with a platform that condemned American actions in the Philippines. Prominent members of the League included Mark Twain, Andrew Carnegie, William James, Jane Addams, and Carl Schurz. The League believed “that it was wrong for the United States to forcibly impose its will on other peoples. No economic or diplomatic reasoning could justify slaughtering Filipinos who wanted their independence.” Mark Twain suggested a new flag for the colony: “Just our usual flag, with the white stripes painted black and the stars replaced by the skull and crossbones.” Carnegie actually tried to buy the Philippines for $20 million, intending to turn the islands over to the Filipinos. The New York Times denounced his plan as “wicked,” and the offer was refused. Carnegie wrote to an expansionist friend once the war began: “It is a matter of congratulation . . . that you have about finished your work of civilizing the Fillipinos [sic]. It is thought that about 8,000 of them have been completely civilized and sent to Heaven. I hope you like it.” William James was disillusioned to see America “puke up its ancient soul . . . in five minutes” at the first whiff of temptation. “God damn the United States for its vile conduct in the Philippine Isles!” James lamented. The League worked hard to inform the public of what was really happening in the Philippines. It published soldiers’ letters recounting atrocities and war crimes. Yet it was unable to generate mass support, and America went on to claim her Empire.