See Also: 10 Strange Christmas Traditions From The Victorian Era

10 Electric (Eel) Christmas Lights

In Chattanooga, Tennessee, Miguel Wattson doesn’t sing for his supper. Not exactly. Instead, he generates electricity that illuminates the lights on the Christmas tree outside his tank at the Tennessee Aquarium. The eel generates electricity when he’s searching for food. The low-voltage charges are transferred to the lights, which blink and flash. When he’s eating or otherwise excited, Miguel generates higher voltage, causing the lights to flash brighter and longer. Kevin Liska, the director of Tennessee Tech University’s iCube center, which contributed the coding for the system that translates Miguel’s shocks into “a voice” that lets the eel shout “SHAZAM!” and “ka-BLAMEROO!,” explained that “electrical engineering” and “emerging business communication” were combined to produce these effects. Using similar equipment, Miguel also tweets (mostly “sound effects”) to his nearly 41,000 Twitter followers. With a little help from his human friends, he also responds to his followers’ comments. His Twitter page shows just how much he enjoys puns, such as “r-eel-y cool” and “I’m eel-ated.”

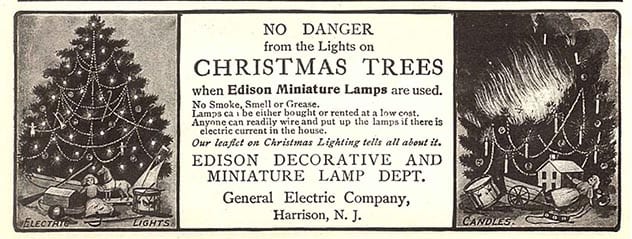

9 Edison Christmas Lights

An early advertisement for “Christmas Lighting,” courtesy of Edison Miniature Lamps, touted the lights as safe, clean, and odor-free. They represented “no danger, smoke or smell.” The lamps could be rented or purchased, but they did have one limitation: they could “be used only in houses having electric lights.” The lamps were invented by Thomas Edison himself. The first strand was exhibited in 1882, on an “indoor tree” in the New York City home of Edward Johnson, Edison Electric Company’s vice-president, and consisted of eighty “red, white, and blue electric colored bulbs.”

8 Metallic (and Plastic) Tinsel

Tinsel has been around since 1610. First used to decorate Christmas trees in Germany, the decorative strips were originally made of silver strands, which reflected the flames of the candles, the trees’ only light source at the time. Admirers of this new decoration regarded the tinsel as suggestive of the Nativity’s star-studded sky. However, since silver soon tarnishes, it was replaced by other lustrous metals, including, at the beginning of the twentieth century, aluminum, and, later, lead foil, neither of which tarnish and both of which are cheaper than silver. In 1972, when exposure to lead became a health concern, tinsel manufacturers and importers agreed to stop making and supplying lead tinsel. Since then, tinsel has been made of “plastic film coated with a metallic finish or . . . Mylar film . . . cut into thin strips.”

7 Rockefeller Christmas Tree Topper

Topping off the huge 2018 Christmas tree in New York City’s Rockefeller Center was a gargantuan task, but BorgDesign Inc. was up to the challenge. The company makes custom parts and machines, including “everything from medical equipment to radars,” for its clients. Although Orion RED, architect Daniel Libeskind, and Swarovski, a European glass manufacturer, collaborated in creating the star, BorgDesign constructed its “core.” The project took roughly seven months, or between 500 and 1,000 hours. “We started working on it, I want to say, in April,” Andrew Borg, the company’s president, explained. “We delivered most of the parts in early October, and we delivered the lifting mechanism right at the end of October.” The lifting mechanism had a big job to do: the star measured nine feet, four inches in height, bore seventy modules composed mostly of LED lights, and featured three million Swarovski crystals, which supplied the topper’s “distinct holiday twinkle.”

6 Inverted Christmas Tree

To stand out, something needs to be as different as an upside-down Christmas tree. Judging by Instagram, such trees were all the rage in 2017, in both shopping malls and family homes across the United States. After setting the tree in place in a modified stand or suspending the base of the tree from the ceiling, with its tip pointing down, employees or family members decorated the fir or pine, hanging ornaments from its inverted branches and piling presents under the treetop. Inverted Christmas trees didn’t first become popular a couple of years ago, though. Holiday trees were first turned upside-down during the Middle Ages to symbolize the Trinity and the crucifixion of Christ.

5Head Ornament

Thanks to 3-D printers, your head, or anyone else’s, can become a Christmas tree ornament. Among more traditional decorations, such as balls and bells, angels and snowmen, and ribbons and bows, your own head, perhaps wearing a red stocking cap with a white pompom, can hang by a ribbon or a hook from a branch of your Christmas tree, facial hair and face (but not blood) included. Sony Xperia came up with this rather eerie idea, using it in a 2017 promotion called Bauble Me. Sony employees showed off the printing process and its final product at “pop-up events” in the United Kingdom, during which, each day, the faces of a hundred shoppers with Xperia smartphones could be “scanned and made into a Christmas ornament,” free of charge.

4 La Befana

Since the eighth century, Italian tradition has included a witch by the name of La Befana. Following the star to Bethlehem, the Magi spent a night in the witch’s home. In the morning, having enjoyed her hospitality, the Wise men invited her to join them on their journey, but she declined, saying she had to stay home to clean house. After their departure, though, she changed her mind and set out on her own, a basket of gifts for the baby Jesus in hand, and followed the star the Wise Men had mentioned. On January 6, the Day of the Epiphany, the Magi found the site they sought, but Le Befana was unable to do so. Ever since, on the Eve of the Epiphany, she sets forth again, seeking the child in every house she passes and offering treats to good children and lumps of coal to naughty ones. Some of the incidents of her story appear, altered, in the story of Santa’s travels on Christmas Eve.

3 Chimney Entrances

There’s a reason that, when Santa opts to gain unlawful entry into millions of homes on Christmas Eve, he enters by way of the chimneys. Washington Irving, the early American storyteller who gave us the Headless Horseman, among other things, is responsible for the modern portrayal of Santa, describing Saint Nicholas in his 1809 book Knickerbocker’s History of New York, as a man “riding jollily among the tree tops, or over the roofs of the houses, now and then drawing forth magnificent presents from his breeches pockets, and dropping them down the chimneys of his favorites.” His use of chimneys is derived from the belief, during the Middle Ages, that witches made their way into houses through chimneys and windows. Consequently, chimneys, in particular, became known as portals between the earthly and the otherworldly realms and were used by such magical beings as Scottish brownies, Irish bodachs, and the Italian Le Befana, a witch who rode a broomstick to deliver goodies to good children. In his description of St. Nicholas, Irving drew on this long tradition, having his character also make use of houses’ chimneys, and, in 1882, Clement C. Moore further popularized the notion that Santa entered homes through chimneys in his poem “The Night Before Christmas.”

2 NORAD Tracks Santa Program

In the United States, even the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) has gotten into the spirit of the Christmas holiday. On Christmas Eve, 1955, a child called Air Force Colonel Harry Shoup at the forerunner to NORAD, then known as the Continental Air Defense Command Operations Center (CADCOC) in Colorado, to inquire into Santa’s “whereabouts.” Thanks to a misprint, the youngster had found the telephone number in a local newspaper. The colonel assured the youth that CADCOC would protect Santa. Calls from other children kept coming all night, as Shoup’s operator updated Santa’s current location. When it was organized in 1958, NORAD inherited the tradition that developed from these calls. A massive undertaking, tracking Santa begins in November and involves seventy “government and nongovernment contributors” and over 1,500 volunteers who field callers’ questions. In 2019, the NORAD Tracks Santa program “received 126,103 calls and answered 2,030 emails, and OnStar received 7,477 requests to locate Santa.”

1Letter Adoption

The United States Postal Service (USPS) receives hundreds of thousands of letters that children have addressed to Santa. As a response to these letters, the USPS started Operation Santa. Now in its 107th year, the operation includes fifteen cities. To protect letter writers’ privacy, their last names and all other “personal information,” including their addresses and other “points of contact,” are redacted, and gifts are matched to their intended recipients by a code. Only letters addressed to Santa Claus, 123 Elf Road, North Pole 88888 are processed through Operation Santa; others addressed to Santa go through regular channels for improperly or incompletely addressed correspondence. Rather than destroying the letters, the Postal Service asks for volunteers who are willing to adopt a letter. Participants pore over the letters, each volunteer selecting one to adopt. Then, acting anonymously, each participant buys at least one of the requested items on the child’s list, packages it, and mails it to the child he or she has selected. Letters are also posted on the USPS website. By registering, volunteers receive children’s letters to Santa, which the USPS redirects to them, and they then buy the children gifts, mailing them to the recipients by December 20.

![]()