10The Girl With The Pearl Earring

Despite all the theories and speculation, no one seems to know the identity of Johannes Vermeer’s girl in the famous 1665 painting Girl with a Pearl Earring. She is turned toward us with soft light glinting off her young face and a large pearl dangling from her ear. She looks as though she’s about to say something, but we have no idea what her story is. Was she Vermeer’s daughter? His lover? It’s possible she never existed in real life, but she still draws huge crowds everywhere her picture is exhibited. In the 17th century, this kind of painting was called a “tronie,” which referred to a study of the face and shoulders adorned with a striking or unusual costume. In this picture, the girl’s turban gives the portrait an Eastern feel with the overly large pearl earring apparently meant to fire the imagination and enhance the aura of mystery. Even Vermeer himself is an enigma. We know he always lived in the town of Delft and had 15 children. Only about 36 paintings are attributed to him. But those few paintings are masterpieces of the interplay of light and shadow on female faces posed against spartan interiors. It’s the mystery created by his paintings, the unanswered questions, that enthrall the viewer. Girl with a Pearl Earring is a timeless example of that. “The image works because it is unresolved,” says Tracy Chevalier, who wrote a popular novel about the painting. “You can’t ever answer the question of what she’s thinking or how she’s feeling. If it were resolved, then you’d move onto the next painting. But it isn’t, so you turn back to it again and again, trying to unlock that mystery. That’s what all masterpieces do: We long to understand them, but we never will.”

9Lightning Strikes Twice

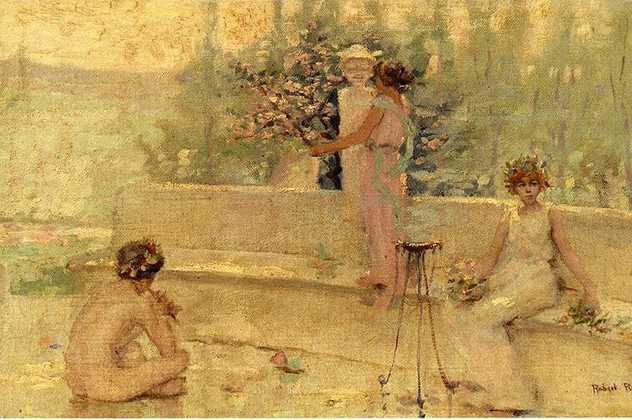

When restoring a masterpiece by Robert Reid, an early 20th-century American impressionist, art conservator Barry Bauman was amazed to find that Reid had concealed another painting under the one to be restored. This hidden painting, dubbed In the Garden, portrayed a young woman seated at a table outdoors who is reading while having tea. Many artists will paint over an existing piece, but Reid had stretched this second painting over the first finished one. No one can figure out why Reid did that, and he’s not alive to tell us. What we do know about Reid is that he was a gambler who died before the worst part of the Depression, although he always struggled financially. Art experts speculate that he may not have liked his first painting, so he tried to save money on supplies. Or it may have been an easier way to ship or store paintings. The odd thing is that this has happened twice in two years in Indiana’s art world. In 2012, Bauman had the same thing happen to a T.C. Steele painting which he was about to restore for Indiana State Museum. It’s tremendous good fortune for Indiana, but it’s the art world equivalent of lightning striking twice. For the Brauer Museum of Art at Valparaiso University, it means that they now own two valuable Robert Reid paintings instead of one. They will probably keep both of them to entice people to visit the museum because of this unusual story.

8The Love And Betrayal Of Wally Neuzil

In the early 1900s, Walburga “Wally” Neuzil was the mysterious muse of Austrian painter Egon Schiele. She appeared in several of his paintings (including some erotic ones), was reputed to have been his lover, and took care of much of the business side of his painting. She appeared in the 1912 masterpiece Portrait of Wally, which was nicknamed the Viennese Mona Lisa for its mysterious smile. Neuzil was from a poor family in Tattendorf, Austria, and she met Schiele when she was 16 years old. She was registered as a salesgirl, not an artist’s model, which often meant a double life as a prostitute. Over time, it became obvious from Schiele’s paintings that his relationship with Neuzil was more than professional. Art experts say that you can see it in the way she looks back at him. Although she was extremely loyal to him, Schiele abruptly dumped Neuzil in 1915 to marry a more respectable woman. It appeared the two lovers never saw each other again. Or did they? “We have this picture of a brutal breakup, and that Wally was never good enough,” says Diethard Leopold, son of an extensive collector of turn-of-the-century Viennese paintings. “But in 1913, the two went on holiday to Traunsee [a lake near Salzburg] with [Arthur] Roessler [who also posed for Schiele]. We found the private photo album. And after the breakup we can prove that she still had contact with his collectors and owned Schiele works. She must have been more accepted than previously thought.”

7David’s Secret Weapon

Controversy surrounds the question of whether Michelangelo’s David was holding a secret weapon, a fustibal, in his excessively large right hand. A fustibal was a sling to hurl stones as far as 180 meters (600 ft). According to the Bible, David had his sling, five stones, and a shepherd’s staff with him when he fought Goliath. Only the sling is visible in Michelangelo’s sculpture from the early 1500s. But some scholars argue that the straps of the sling connect to an unidentified item in David’s hand, believed to be a handle for the staff which would function like a golf club. The statue was originally meant to be placed on top of the Florence Cathedral, where the weapon would have been hidden from view. David’s fustibal was visible in other artists’ paintings of the time, which these experts believe influenced Michelangelo’s rendering of his famous sculpture. However, they think that the staff wasn’t mounted on the handle for political reasons. “A shepherd staff wasn’t fitting with the political meaning of the statue, which became the first public Italian monument,” said art historian Sergio Risaliti. Not all experts agree with this theory, so the mystery of the object in David’s hand remains unsolved.

6The Jesus Statue With Real Teeth

A 300-year-old statue of Jesus in a small Mexican town was accidentally discovered to have real human teeth with roots. No one knows where the teeth came from. In a religious tradition from earlier times, it was common for people to donate human body parts to their churches. Human hair or teeth carved from animal bones frequently adorned statues, but until now, no one had ever seen human teeth in a statue. Created in the 17th or 18th century, this Christ of Patience statue was in the process of being restored when X-rays revealed human teeth in surprisingly good shape. It’s unclear if the teeth came from a living or dead person, or maybe even more than one person. It’s also possible that the teeth were forcibly extracted from someone and donated against their will. Even more strange, the statue’s mouth is almost completely closed, so the teeth aren’t visible unless you deliberately look inside. So why use a set of teeth in such good condition? There’s really no way to determine who the donor was. Nevertheless, without removing the teeth, researchers want to determine the age and gender of the donor. “For [modern people], it seems mad,” said restorer Fanny Unikel Santoncini. “[But] the way they thought about the body was different from ours.”

5The Man Under The Woman Ironing

Using an infrared camera, a second painting was discovered under Pablo Picasso’s prized 1904 painting Woman Ironing after an attempted robbery damaged the canvas. The second picture is an upside-down image of a man with a mustache. Scholars are haunted by questions of who the man was and whether Picasso painted him. They’ve ruled out a self-portrait of Picasso. The painter was only 22 years old and living in Paris when he created the early masterpiece Woman Ironing. It was from his Blue Period, which was dominated by somber subjects in mostly blue tones. However, he was always strapped for cash and frequently repainted over his canvases. Some experts believe that the brush strokes and type of paint used on the hidden picture confirm that Picasso painted it. But there is intense debate as to who is portrayed in the painting. He appears to be another artist, possibly sculptor Mateu Fernandez de Soto or painter Ricard Canals. However, the more the experts research, the more they disagree. Another hidden portrait was discovered under the Picasso masterpiece The Blue Room. Like Woman Ironing, this painting is also from his early Blue Period in Paris. Infrared technology revealed a man with a beard wearing a bow tie and jacket. It was the unusual brushstrokes on the top painting that propelled scientists and art experts to probe further with this one. Again, it doesn’t appear to be a self-portrait, but the man’s identity and relationship to Picasso is a mystery. “Our audiences are hungry for this,” said Dorothy Kosinski, director of The Phillips Collection. “It’s kind of detective work. It’s giving them a doorway of access that I think enriches, maybe adds mystery, while allowing them to be part of a piecing together of a puzzle. The more we can understand, the greater our appreciation is of its significance in Picasso’s life.”

4Study By Candlelight

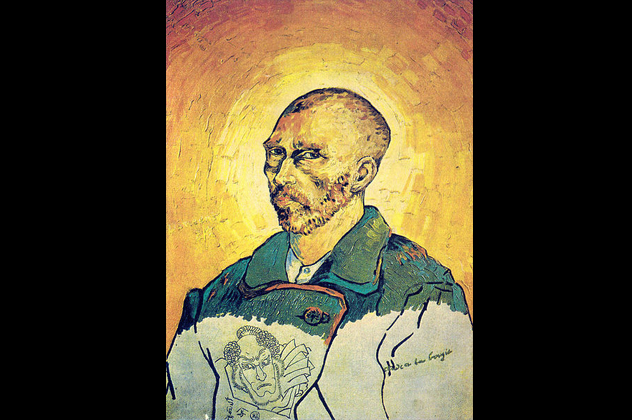

The controversy with Study by Candlelight is whether it’s a real painting by Vincent Van Gogh or a forgery, as claimed by his nephew. It looks like a self-portrait of Van Gogh, but the lower third of the painting is unfinished and contains a strange Japanese kabuki character. The character was added in ink, not paint. There’s also a question of why French accent marks don’t appear on the inscription “Etude a la bougie,” which means “study by candlelight” in French. The painting was first purchased by William Goetz, the head of Universal Pictures, in 1948. At that time, the artwork had been authenticated, but Van Gogh’s nephew declared it a fake soon afterwards. Another art expert agreed with the nephew, kicking off a decades-long dispute over the authenticity of the painting. In 2005, a book about Hollywood forger John Decker declared that Decker purposely forged artwork that he attempted to trick Goetz into buying. While modern technologies can tell us about the materials used in the painting, the analysis can’t resolve the question of who actually painted Study by Candlelight and placed a Japanese kabuki drawing on the canvas. Only Van Gogh knows that information, and he took it with him to the grave.

3The Missing Ballerina

No one knows whether Edgar Dega’s painting of a ballerina, Dancer Making Points, was given away, thrown out, or stolen from wealthy heiress Huguette Clark’s apartment in the 1990s. But when it reappeared in the home of Henry Bloch, art collector and co-founder of H&R Block, Clark tried to stop the FBI from investigating by saying that she valued her privacy. Although she never declared the painting to be stolen, a legal battle ensued between Clark and Bloch. Bloch bought the painting in good faith, so the court battle hinged on whether he could keep it on the basis of “finders keepers.” However, both sides eventually crafted a complex settlement that returned the painting to Clark, whose attorney immediately donated it to the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, where Bloch is a trustee. Clark got a hefty tax deduction and the Blochs are allowed to hang the painting in their home until they die, at which time it goes to the museum. At the time of the settlement, the museum insisted on a sworn statement from Clark’s doctor confirming that she was mentally competent at 102 years old to make the gift. Dr. Henry S. Singman provided that statement. However, the settlement may be in jeopardy because Clark signed two different wills in 2005, the second of which excluded her family members as inheritors. But Dr. Singman, among others, was named as a beneficiary in the second will. If the family successfully invalidates this second will in court, as they’re attempting to do, then the settlement between Bloch and Clark may also be invalid. Was the elderly Clark in possession of her senses when she drew up her second will or did someone influence her for monetary gain? If she wasn’t competent in 2005, then she would most likely be deemed incompetent in 2008 when she signed the settlement with the Blochs. It’s a convoluted case with a lot of unanswered questions. Clark died in 2011 at the age of 104.

2The Connecticut Connection To The Gardner Heist

In 1990, the world’s greatest art heist occurred at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston. Paintings by Edgar Degas, Rembrandt, and Jan Vermeer were among the almost $500 million worth of masterpieces stolen by two men pretending to be policemen. At the time, FBI agent Paul Cavanagh said, “This is one of those thefts where people actually spent some time researching and took specific things. The job was a professional job.” In 2010, mobster Robert Guarente’s widow informed police that, several years before his death, her husband had asked Robert Gentile to hide two or three paintings from the Gardner heist. The FBI considered Gentile to be an aging hoodlum. After he failed a polygraph exam about his involvement with the stolen artwork, he connived to take the test again. This time, he admitted to having seen the stolen self-portrait by Rembrandt. The polygraph showed that he was telling the truth. Then he claimed that Guarente’s widow had shown it to him and said it would fund her retirement. Effectively, Gentile shifted the blame back to the woman who had fingered him. But he wouldn’t snitch further. While Gentile sat in prison, FBI agents searched his property in Connecticut for evidence in the theft. In the basement of Gentile’s house, they found a paper listing the 13 pieces of stolen artwork along with their estimated values on the black market. The paper was stuffed into an old newspaper reporting the theft. Gentile’s son mentioned to the FBI agents that his father stored valuables in a plastic container under a false floor in his shed, but the FBI found nothing there. Then, Gentile’s son told them of a rainstorm that had flooded the pit underneath the shed, stating that it had destroyed whatever was there and upset his father greatly. When questioned again, Gentile still revealed nothing. In his seventies and in poor health, he only got a sentence of 30 months. He was released by January 2014. But in March 2013, the FBI’s Boston office publicly announced they were confident that organized crime was responsible for the Gardner heist. The FBI said they knew who stole the paintings and that the artwork had been delivered to Connecticut and Philadelphia. They didn’t give any more details. However, from their sources, some newspapers identified David A. Turner as the person who organized the heist, Robert Guarente as the person who hid the paintings, and Robert Gentile as the fence. The FBI hoped that the announcement would trigger the public to look for hidden paintings in their garages and attics or get someone to make a call with relevant information that would be picked up on a wiretap. Neither of those things happened. The investigation was soon eclipsed by the more important Boston Marathon bombing.

1The Other Mona Lisas

Many people believe there’s only one Mona Lisa, the famous one at the Louvre in Paris. However, a second Mona Lisa sits in the Prado Museum in Madrid that may have been painted by da Vinci or one of his students simultaneously with the first. This second painting has a slightly different perspective, which can create a 3–D effect when viewed with the original Mona Lisa. “This points to the possibility that the two [paintings] together might represent the first stereoscopic image in world history,” researchers wrote in Perception. They also believe that the mountains in the background of the painting were created on a separate canvas that was placed behind the woman. That’s no different than what you would see in a portrait studio today. Experts disagree on whether the two paintings were created simultaneously and whether this 3–D effect was meant to occur or just happened accidentally. In another surprising discovery, there’s a third Mona Lisa, an earlier version known as the Isleworth Mona Lisa. She’s believed to be about a decade younger in this painting than the other two. Is this painting the “missing link” between da Vinci’s earlier and later styles of painting, a forgery, or the real deal? The Isleworth Mona Lisa seems to have been painted when da Vinci was alive, but that doesn’t mean he painted it. One of his students may have created this version. Also, most of da Vinci’s paintings were done on wood. The Isleworth Mona Lisa was painted on canvas. Was da Vinci experimenting with a different technique or was there another creator? If da Vinci did produce this version, which many experts believe, then why did he paint Mona Lisa at least twice? Among the experts, there’s continuing controversy about these paintings which we’ll likely never resolve. But the Isleworth Mona Lisa is in almost perfect condition, which raises the question of whether it’s truly 500 years old. According to at least one expert, it seems unlikely that a painting could have survived so well for so long.