10Park Station Bombing1970

San Francisco PD Sergeant Brian McConnell died when a bomb exploded at the Park Police Station on the night of February 16, 1970. At 10:45 PM, while McConnell was sorting through paperwork and keeping an eye on the recent police union election, a time bomb detonated from a nearby window. Inside of the bomb were a series of upholstery staples that not only embedded themselves into Sgt. McConnell’s face and upper torso (he would die two days later) but also gave shrapnel wounds to eight other officers and administrators. Almost immediately, left-wing radical groups like the Weather Underground and the Black Liberation Army were suspected. Despite this, the case remains officially unsolved. In 1999, the case was reopened by a federal grand jury. The jury did not immediately release its findings, and it would take over a decade before another jury concluded that the bomb was the work of the Black Liberation Army. The San Francisco Police Union, however, has publicly pinned the bombing on Bill Ayers, a former Weather Underground leader and the one-time teacher of President Obama.

9Preparedness Day Bombing1916

Even though the United States had yet to enter the First World War in 1916, tensions across the country were still very high. Two camps in particular were responsible for the conflict—those who wanted the country to enter the war on behalf of the Allies and those who wanted the country to remain neutral no matter what. The former camp included men like former president Theodore Roosevelt and General Leonard Wood, who was in charge of the Preparedness Movement that sought to both strengthen the American military and “prepare” the home front for the eventual war. The latter group included many anti-imperialists, socialists, progressives, and members of the radical IWW labor union. These factions met on July 22, 1916, when a Preparedness Day parade marched through San Francisco. Outside the patriotic bunting and cheering crowds, many antiwar demonstrators jeered and held their own counterprotests. During the 3.5-hour long march, which included a little under 52,000 individuals, a suitcase bomb exploded, killing 10 and wounding 40. Within no time, police and private detectives accused Tom Mooney, a radical labor organizer, of planting the bomb. Under trumped-up evidence, Mooney was convicted and sentenced to death until President Woodrow Wilson commuted his sentence to life imprisonment on November 29, 1918. After serving over two decades in prison, Mooney was pardoned in 1939, thus forcing a reexamination of the case. Today, three explanations for the bombing remain popular: 1) the bombing was the work of radical labor unionists, 2) the bombing was an act of German sabotage, and 3) the bomb had actually been planted by private detectives and industrialists interested in tarring the antiwar movement as violent and bloodthirsty.

8LaGuardia Airport Bombing1975

Despite the rhetoric of the post-9/11 War on Terror, terrorism in the United States is nothing new. Before and after World War I, the wave of “red terrorism” was so huge, so seemingly all-encompassing, that the American government took what were at the time unprecedented measures to both minimize immigration from Europe and clamp down on those radical ideologies already active in the country. In the 1970s, another tsunami of violence washed over the headlines, with skyjackings, assassinations, and bombings being common. Amazingly, this era of terrorism did not cause any great changes in law enforcement or security procedures. It was during this time that a bomb exploded in New York’s LaGuardia Airport. On the night of December 29, 1975, a bomb hidden inside a coin-operated locker exploded around 6:30 PM. The bomb, which was the equivalent of 25 sticks of dynamite, managed to kill 11 and wound 74. Most of the victims died due to shrapnel wounds, while a collapsed ceiling and floor also contributed to the body count. At first, many suspected that the bombing had been done by the FALN, the Puerto Rican nationalist group that had carried out a deadly bombing at the Fraunces Tavern earlier that year. Palestinian organizations, such as the PLO and Black September, were also suspected, but ultimately no group claimed credit for the attack. The most likely culprit, the Croatian nationalist and convicted skyjacker Zvonko Busic, never confessed to the crime. That said, the MO and IED used in the LaGuardia bombing were reminiscent of Busic’s hijacking of a TWA flight traveling from New York to Chicago in September 1976. Interestingly, Busic’s hijacking originated at LaGuardia.

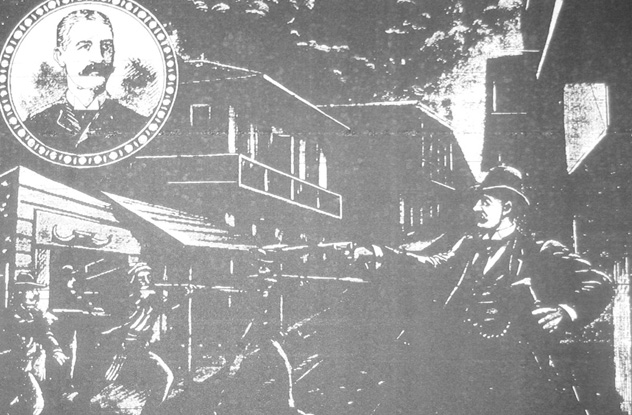

7Central Police Station Bombing1917

As part of their revolt against capitalism, radical anarchists and socialists frequently targeted police officers and other public officials. Violence was common, with bombings being the preferred method of attack. Milwaukee, a city controlled by socialists, was not spared. In November 1917, following a series of well-publicized confrontations between local anarchists and Protestant missionaries, a bomb ripped through Milwaukee’s Central Police Station. In the aftermath, responders found nine dead policemen and one dead civilian. Until September 11, 2001, the bombing of the Central Police Station was the deadliest day in the history of American law enforcement. Although the bomb exploded in the police station during roll call, it was actually found outside the Italian Evangelical Church before being taken back to the station. Reverend Augusto Giuliani, the church’s anti-anarchist, pro-war pastor, was the intended target. Because of this, members of the Francisco Ferrer Anarchist Circle remain the most likely perpetrators. Indeed, 11 members of the mostly Italian anarchist group were arrested and convicted for assault and intent to commit murder, although the actual bombers were never caught.

6July Fourth Bombing1940

America was still trying to crawl itself out from underneath the Great Depression while most of the world was already at war during the summer of 1940. A majority of Americans wanted nothing to do with fighting the Nazis, the Italian fascists, or the Japanese imperialists. Still, violence and intrigue managed to touch isolationist America, even at the World’s Fair. From 1939 until 1940, New York City hosted the World’s Fair—an elaborate celebration of technology, culture, and the possibility of a better, more advanced future for the world’s inhabitants. But on July 4, 1940, a single bomb managed to dampen the enthusiasm of the event’s organizers. On that day, two bomb squad detectives, Joe Lynch and Ferdinand Socha, were called in to diffuse a ticking device planted near the British Pavilion. Tragically, the bomb exploded in their faces. The bomb, which was more or less several sticks of dynamite inside a canvas bag, left behind a crater that was 1 meter (3 ft) deep and 1.5 meters (5 ft) wide. The bomb also left behind many questions, most of which have never been answered. First and foremost among those questions was, “Who was responsible?” While some have mused that the British government, who desperately wanted America to join the Allied war effort, was behind the bomb, others have pointed toward George Metesky, the notorious Mad Bomber of New York City.

5Times Square Bombing2008

Even in New York City, 3:30 AM is not a time when a lot of people are up and around. So when an IED placed next to a military recruiting station in the heart of Times Square exploded, no one died or was injured. Almost eight years on, no suspect has been named, but a person of interest was mentioned by the FBI In early 2015. This person of interest may also be connected to a series of similar bombings that occurred in Manhattan during the mid-2000s. According to the FBI’s website, the bomb outside the recruiting station was housed inside an ammo can and mostly contained black powder. Furthermore, the suspect, who left the scene on a blue “Ross” bicycle, wired the bomb with a time fuse, thus making it likely that the bomb was not intended to produce a mass casualty event. That being said, the bomb’s structure was very similar to the type of deadly IEDs used by Islamist insurgents in Iraq and Afghanistan.

4The Midair Explosion Of United Flight No. 231933

As the airplane traveled toward Chicago during the night, no one onboard expected that they would soon ride into history as part of a tragic mystery that remains unsolved to this day. On October 10, 1933, the Boeing 247, which was operated by United Airlines, exploded midair over Jackson Township (some sources say Chesterton), Indiana. All seven onboard, including the passengers and the entire crew, died. It was later discovered that the plane had been intentionally destroyed by a bomb planted either in the baggage area or the lavatory. In 1933, air travel was in its infancy, and very few people used it as a common means of transportation. As evidence, only three travelers were aboard United Flight No. 23. These three people—Emil Smith and Fred Schoendorff of Chicago and Dorothy M. Dwyer of Arlington, Massachusetts—later became suspects, but all lacked the necessary motivations for carrying out such an attack. Similarly, the plane’s crew members are equally unsuspicious. Because of this, some have asserted that the bombing was the work of everything from organized crime to organized labor. The destruction of United Flight No. 23 is not only the first major terrorist attack in aviation history, but it’s also the first in a series of midair explosions. But despite this attack’s importance in the history of terrorism in America, the case continues to be ice cold.

3The David Hennessy Tragedy1890

New Orleans in the 19th century was a city rotten with political corruption and conflict. After suffering defeat in the Civil War, the proudly Southern port city was briefly ruled by Republicans until the Democrats, who were emboldened by the Compromise of 1877, regained control and tried to reinstitute some prewar social and economic policies. The Democrats of the 1870s were not terribly united, however. On one hand, a large, powerful percentage of New Orleans Democrats were loyal to an antebellum political machine that primarily fought for the interests of rural planters and urban workers, many of whom were recent immigrants from Ireland and Germany. On the other hand, the Democrats also included “Reformers,” white collar merchants and professionals who wanted to rid the party of machine politics. David Hennessy, the son of a former soldier in the Union army who was murdered by a fellow New Orleans police officer while in a barroom, got ensnared in these rivalries during his time as the city’s top cop. The successful officer had made detective early thanks not only to his father’s legacy but also to his own crusade against the Sicilian mafia that taken up residence in the city. Hennessy nonetheless courted controversy. On Halloween 1881, Hennessy was involved in the shooting of Thomas Devereaux, a police detective who was the chief suspect in the murder of Robert Harris, another New Orleans police detective. At his trial, Hennessy claimed self-defense and was found not guilty. Hennessy’s dance with good fortune would run out, however. By the morning of October 16, 1890, Hennessy was dead, the victim of an assassin’s bullet. Before dying, Hennessy told those around his hospital bed that “dagoes” were responsible for his dire condition. When Hennessy’s words were picked up by the New Orleans press, the police zeroed in on members of the Sicilian mafia, especially those connected with the feuding Matranga and Provenzano crime families. However, after 19 Sicilian and Italian immigrants were arrested for the murder of Chief Hennessy, all were exonerated due to a lack of evidence. Incensed, a large crowd initially gathered to protest the verdict, but soon enough, the protest turned into a lynch mob. The armed crowd succeeded in overrunning the city jail and hanging the suspects one by one. As was the case with Hennessy’s murder itself, no one was brought to justice for the lynchings.

2The Murder Of Officer Richard Radetich1970

The years between 1967 and 1971 were an extremely tough time to be a cop in San Francisco. Due to the furor emanating from the antiwar and hard-left crowd, SFPD officers were frequently the targets of activist rage. Most of the time, this meant that officers were spat upon, punched, kicked, or hit with rocks. On other occasions, officers died outright. One such case occurred on June 19, 1970, when 25-year-old officer Richard Radetich died with three shots from a .38-caliber revolver. The perpetrator had crept up on the driver’s window of Officer Radetich’s cruiser. Inside, Officer Radetich was oblivious to the intruder until it was too late. When Officer Radetich died 15 hours later, he left behind a widow and an eight-month-old daughter. Given that the infamous Zodiac Killer was active during the time, many in the press jumped to the conclusion that the serial killer was responsible for Officer Radetich’s murder. The killing was somewhat similar to the murder of Paul Stine, the final official victim of the Zodiac Killer. Although an unnamed subject was originally arrested for the murder, they were released in January 1971. Since then, the case has gone ice cold. Some continue to believe that the murder was the work of the Zodiac, while others have pointed to terrorist groups such as the Weather Underground and the Black Liberation Army.

1Miami Is Burning1951

In December 1951, after a series of dynamite attacks on black, Catholic, and Jewish homes and institutions, Bill Hendrix—the Grand Dragon of the Florida KKK—told the press that his group was neither involved nor sympathetic to the dynamiting conspiracy. The violence had gotten so bad and so outrageous that the Ku Klux Klan had to publicly state that they were not responsible. Whether or not the KKK was involved, the attacks unquestionably tarnished Miami’s image as a sunny American paradise. Furthermore, the attacks, which led journalist Stetson Kennedy to call the city an “anteroom to Fascism,” hurt not only the city’s civic elite (most of whom were white Protestants), but also the city’s growing Catholic, Jewish, and black populations, all of whom were gaining some measure of political clout in the 1950s. While many in the press focused on how abnormal and rare such bombings were in the city, others used the bombings as a way to criticize the city’s lax standards when it came to cracking down on gambling and other criminal activities. In hindsight, it’s clear that the bombings were carried out to keep blacks, Catholics, and Jews away from the city, especially the city’s many high-end communities and residential neighborhoods. While the bombings failed to halt the growth of non-Protestant and non-white communities in Miami, they did help to further stoke the city’s already simmering racial tensions, especially since the bombings were never solved. Benjamin Welton is a freelance writer based in Boston. His work has appeared in The Atlantic, The Weekly Standard, Listverse, Metal Injection, and other sites. He currently blogs at literarytrebuchet.blogspot.com. Read More: Twitter Facebook The Trebuchet