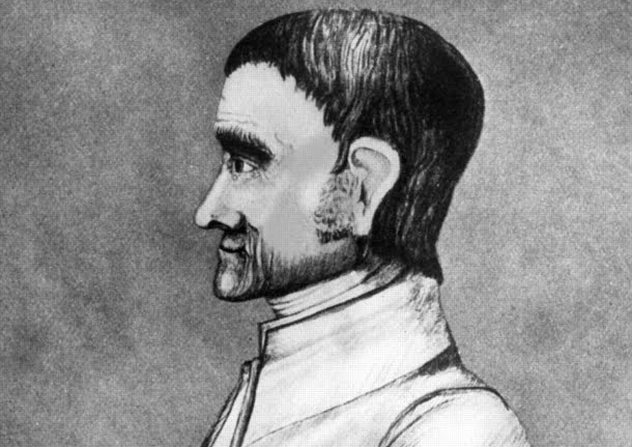

10John Woolman

Woolman was a quiet Quaker in 18th-century Pennsylvania. His hobbies included tailoring clothes, enjoying spiritual nature hikes, and taking unarmed solo expeditions deep into dangerous Indian territories. Woolman’s intent there was pretty commendable: He just wanted to learn about the natives while spreading a message of brotherly love. As he gained respect for the neighboring tribesmen, he began to feel a bit conflicted on the matter of human rights, particularly in regards to slavery. For around 20 years, he traveled throughout the colonies—and even back to England—gently advocating against slavery to members of his religion. Even those who disagreed with him found comfort in his peaceful, serene nature, and—because he was never accusatory, always patient—he managed to convince a number of people of the error of their ways. In fact, the Religious Society of Friends (aka “Quakers”) abolished slavery in 1776, just four years after his death, and a full 89 years before the whole country followed suit.

9Judith Sargent Murray

A lesser-known feminist of her era, Murray was a dazzlingly bright woman with a vision to empower her gender. By the age of 23, she was writing and publishing under the guise of a man, encouraging her fellow females to get educated and involve themselves in their communities. A pretty tough cookie, she refused to be swayed from her pursuit of gender equality, even when she was excommunicated from her church and abandoned by her husband, who, fearing debtor’s prison, fled to the West Indies (he ended up dying there a few years later). Apparently, her second husband was no great shakes at money management either—the couple was in debt soon after they married, and it was the publication of Murray’s columns, plays, and pamphlets that kept them afloat. Judith’s place in history is pretty noteworthy: Today, she is recognized as the first woman to self-publish a book—The Gleaner—and as the very first American to have a play produced in Boston (The Traveller Returned).

8Peter Francisco

This spirited war hero began his life in colonial America in a rather unique way: He showed up alone on a beach in Virginia at the very young age of four. It’s believed he was kidnapped from the Portuguese Azores, where he lived with his aristocratic family, and taken by boat to the New World, though the exact circumstances surrounding his abduction are unclear. Upon arrival in the colonies, he was taken in by Judge Anthony Winston. Winston took him home to be raised on his plantation, where Francisco grew into a very passionate revolutionary. We mean “grew” quite literally: At 14, Francisco weighed a healthy 118 kilograms (260 lb) and stood at 198 centimeters (6’6″)—a full head taller than most full-grown men of his day. At 16, he enlisted in the army and immediately joined the fight for independence. He’s known for a number of heroic feats throughout his service, but the most remarkable is this: In 1779, he was one of 3,000 rebel troops facing an enormous British offensive in the Carolinas. They were outmanned from the get-go, but that didn’t stop Francisco from being a tremendous hero. According to popular legend, even when he knew all was lost, Francisco single-handedly carried a 500-kilogram (1,100 lb) cannon that had been abandoned by the British over to a group of rebel soldiers, who proceeded to use it in the fight. Stopping to rest beneath a tree, Francisco was approached by two British cavalrymen. He held up his musket in surrender, and as the men drew nearer to take it from him, he hit one of them forcefully enough to knock him from his horse, stabbing his bayonet through the other cavalryman at the same time. He then took one of their horses, as well as a sword, and galloped away.

7Nancy Hart

Here’s a woman who refused to let the men have all the fun in the Revolutionary War. While her husband, a lieutenant in the Georgia militia, was off fighting the British, she remained at home to tend to the children and farmhouse—and spy on the Redcoats. She was known to dress up, act like a “simpleminded man,” and wander into British camps to gather information that she then passed to revolutionary authorities. Her defiance knew no bounds, as evidenced by one group of six Tory men who met their match when they made the mistake of messing with Mrs. Hart. They arrived at Hart’s farmhouse, demanding food and drink. Nancy opened some bottles of wine and secretly sent one of her daughters out the back door to blow a conch shell and alarm the neighbors of the unwanted guests in her cabin. As the Tories grew progressively drunk, Nancy began passing their weapons to her daughter in the backyard through a hole in the chink of her cabin. When the Tories realized what she was up to, she went on the defensive and held them at gunpoint with one of their own weapons, shooting one Tory who decided not to keep his distance from her. Her husband arrived shortly after—he wanted to shoot them all, but she insisted they be hanged.

6Martha Ballard

A midwife in upstate Maine during the mid-1700s, Ballard may not have contributed anything overtly revolutionary to the era, but she did keep a diary that has shed light on the day-to-day life of a typical person during that time period. At first glance, her diary seems pretty dry—it’s basically a record of the more than 800 births she attended to over the course of her employment—but upon further inspection, it’s a pretty amazing glimpse into the challenges facing the early inhabitants of the colonies. Ballard herself had to deal with a number of grievances, including ignorance from male doctors. During one childbirth, Martha watched with annoyance while a young, inexperienced doctor administered opium to the mother, and then walked away, leaving Martha to wait for the drug to wear off before delivering the baby—which she did, without complications. Martha also wrote about the deaths of some of her own children, instances of domestic abuse in her community, and the pressure to run a household while pursuing her livelihood in midwifery (which sometimes meant traveling miles in inclement weather, through the backwoods of Maine, by herself).

5George Middleton

Known for his charismatic personality and ability to fraternize with pretty much everyone, Middleton was one of Boston’s free black men, and quite an influential one at that. In the late 1700s, Middleton established the Boston African Benevolent Society, which acted as a social services organization, providing jobs and homes to the needy in his community. He was also an active anti-slavery campaigner. For these contributions to his community, Middleton has been heralded as a champion of social justice in the colonial era. His unconventional living arrangements have also made him a hero to the queer community. According to The History Project, Middleton built and inhabited a house with a close male friend by the name of Louis Glapion. They lived together for many years until Glapion married. Even then, they just split the house in two, with the Glapions living in one half and Middleton in the other. In those days, it wasn’t uncommon for gay people to marry heterosexually while maintaining homosexual relations on the side, and some historians have speculated that Middleton and Glapion had a romantic relationship. If that was the case, they certainly weren’t bashful about sharing their lives with the community. Their house was quite a happening place, actually. According to one neighbor, their house “thronged with company.” History nerd bonus: The Middleton-Glapion house is still standing in the historic Beacon Hill neighborhood of Boston.

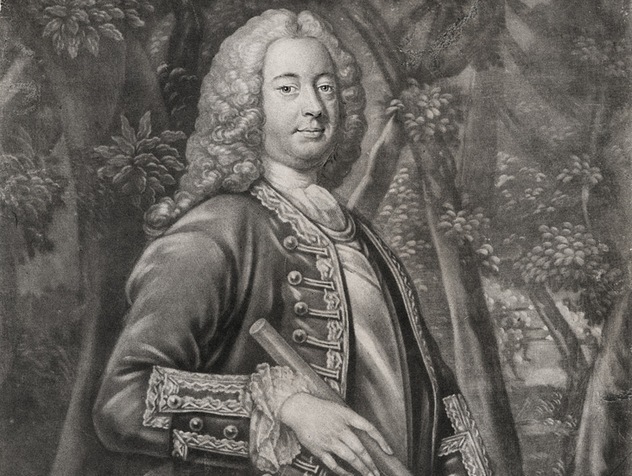

4William Johnson

A competent and skilled negotiator, Johnson served as the Superintendent of Indian Affairs in the mid-1700s. He was one of the wealthiest men in colonial America, though this powerful position did not persuade him to deal cruelly with the neighboring Native Americans, as so many of his fellow colonists did. On the contrary, a prime piece of Johnson’s large estate bordering the Mohawk River remained open and accessible to the natives, and actually ended up becoming a hub for trade and socializing among the Mohawk people. Johnson attempted to bridge the gap between colonists and natives by educating the Native Americans on aspects of European culture. After his wife died, he married a Mohawk woman, and when she followed his first wife in death, he married another. When the French and Indian War broke out in the Ohio River Valley, Johnson, by that time a major-general, led colonial and native forces to several significant victories, all while maintaining the support of the venerable Iroquois Confederacy.

3Dicey Langston

At 15 years old, Laodicea Langston shouldered a much bigger burden than the constant mispronunciation of her name (seriously, how do you say that?). It’s actually kind of amusing that she went by the nickname “Dicey,” as that is exactly how we’d describe the circumstances she put herself in. Dicey was the daughter of a South Carolina Whig who found himself sought after by the Bloody Scouts, a gang of violent Tories. The Tories suspected that Mr. Langston was spying on them and passing information to rebel forces, so they kept a close eye on Dicey’s family. Incidentally, the Tories were spot on. Dicey received word that the Bloody Scouts planned to attack a group of Whigs, including her three brothers, at a place called Little Eden, about 8 kilometers (5 mi) from her home. Not trusting anyone else with the information, and apparently undaunted by the bloodthirsty mob of men after her family, Dicey set out in the dead of night and traversed a raging river to warn her brothers of the ensuing attack. They were able to clear out the town quickly, and by the time the Bloody Scouts arrived in the morning, there was nobody to attack. Dicey returned home only to find her father in another precarious situation: The Bloody Scouts, enraged about their revealed attack, assumed Mr. Langston had been in on it. They resolved to kill him, pointing a pistol at the elderly man’s chest, but Dicey stepped in between her father and the gun. According to sources, this act of valor shook the Bloody Scouts to the point of respect, and they left peacefully.

2Jeremiah O’Brien

In the spring of 1775, just as fighting broke out at Lexington and Concord, the inhabitants of a small town in Maine were watching the coastline for two Bostonian ships carrying supplies the colony relied upon. When the anxiously awaited supply ships pulled into port, the colonists were angry to discover that they were accompanied by an armed British ship called the Margaretta. The Margaretta, under the direction of Lieutenant Moore, was to be loaded with lumber and taken back to Boston to build quarters for the Redcoats. Understandably, the colonists were outraged at this. Their original plan, to hijack the ships and kidnap the captain and lieutenant, backfired when the British sensed their hostility and hightailed it for the ocean. That’s when Jeremiah O’Brien entered the picture, gathering 40 men and boarding one of the Bostonian supply sloops in pursuit of the British. Armed with pitchforks, axes, guns, and swords, and using planks to protect themselves from British cannon, the colonists chased down the Margaretta, finally slamming into and boarding the schooner to engage in hand-to-hand combat with the British on board. The captain was killed, and the British were defeated in this first sea engagement of the Revolutionary War.

1Elizabeth “Betsy” Hagar

This woman definitely deserves a bit of credit. In 1759, after being orphaned at the age of nine, Betsy Hagar became a “bound girl,” migrating around the homes of colonists who gave her shelter in exchange for her servitude. Somehow, in the mix of this, she cultivated a unique skillset for her age and gender: a handiness with machinery and tools. When the Revolutionary War broke out, Betsy collaborated with a local blacksmith to refurbish old firearms for use against the British. Because it was (and still is) illegal to make weapons to use against the government, this work had to be done in secret, in a small room attached to the smith’s shop. Betsy is known to have refitted a number of cannons, matchlocks, and muskets, as well as forging the corresponding ammunition for these firearms. She also spent much of her time healing the battlefield wounded, gaining bedside experience and sharpening her medical skills. She carried this expertise into her golden years, where she continued to practice medicine and was one of the pioneers of the smallpox inoculation. I’m a Utah native who enjoys camping, whiskey drinks, and reading books in hammocks. Email: [email protected].