We typically either cremate or bury the deceased, based on religious and personal beliefs. However, people from around the world practice an array of unusual rituals (to Western sensibilities) in order to commemorate and dispose of the dead. Here are ten of those practices.

10 Sati

Sati (also spelled suttee) is a Hindu practice in which a recently widowed woman is burned to death on her husband’s funeral pyre. This is either done voluntarily or by the use of force. Other forms of sati also exist, such as being buried alive and drowning. This practice was particularly popular in Southern India and among the higher castes of society. Sati is considered the highest expression of wifely devotion to her dead husband. The practice was outlawed in 1827, but it has still occasionally occurred in some parts of India.[1]

9 Mortuary Totem Poles

Totem Poles refer to the tall cedar poles with multiple figures carved by Native Americans of the Pacific Northwest. Mortuary totem poles, especially those of the Haida people, have a cavity on top which is used to hold a burial box containing the remains of a chief or important person. These remains are placed in the box a year after the death. The box is hidden from view by a frontal board, which is carved or painted with a lineage crest and placed across the front. The shape and design of the board give it the appearance of a large crest.[2]

8 The Viking Funeral

The Vikings’ funeral and burial rituals were affected by their pagan beliefs. They believed that death would lead them into an afterlife and into one of the nine Viking realms. Because of this, they tried their hardest to send the deceased to a successful afterlife. They typically did this either by cremation or inhumation. The funeral of a Viking chief or king was much more bizarre. According to an account of one such death ritual, a chief’s body was placed in a temporary grave for ten days while new clothes were being prepared for him. During this time, one of his thrall women had to “volunteer” herself to join the chief in the afterlife. She was then guarded day and night and given plenty of alcohol. Once the funeral ceremony started, she had to sleep with every man in the village. She was then strangled with a rope and finally stabbed by the village matriarch. The bodies of the chief and the woman were then placed on a wooden ship, which served as the cremation pyre.[3]

7 Ritual Finger Amputation Of The Dani People

The Dani people of Papua New Guinea believe that physical representation of emotional pain is essential to the grieving process. A woman would cut off the tip of her finger if she lost a family member or a child. In addition to using pain to express sorrow and suffering, this ritual finger amputation was done to gratify and drive away the spirits as well. The Dani tribe believes that the essence of the deceased can cause lingering spiritual turmoil. This ritual is now banned, but evidence of the practice can still be seen in some of the older women of the community, who have mutilated fingertips.[4]

6 Famadihana

Famadihan-drazana, also known as Famadihana, is a ceremony that is used to honor the dead. It is the most commonly practiced traditional festival in the southern highlands of Madagascar. It occurs every seven years during winter in Madagascar, from July to September. Tears and crying are banned, and the ceremony is seen as festive, unlike that of a burial. The ritual starts when the corpses are exhumed from their graves and rewrapped in new shrouds. Before the bodies are reinterred, they are hoisted up and carried around their tombs several times so that they can become familiar with their resting places. Famadihana also offers a chance for deceased family members to be reunited in one single family tomb. The celebration features loud music, dancing, parties with lots to drink, and feasting. The last Famadihana was in 2011, which means the next one will probably start soon.[5]

5 Sallekhana

Sallekhana, also known as Santhara, is the last vow prescribed by the Jain ethical code of conduct. It is observed by Jain ascetics at the end of their life by gradually reducing the intake of food and liquids until they are fasting at the end. The practice is highly respected in the Jain community. The vow can only be taken voluntarily when death is near. Sallekhana can last up to 12 years, which gives the individual time to reflect back on life, purge old karmas, and prevent the creation of new ones. Despite the controversy, the Supreme Court of India lifted the ban on Sallekhana in 2015.[6]

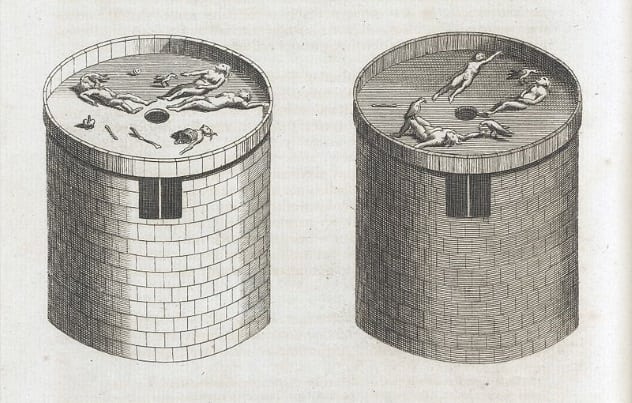

4 Zoroastrian Towers Of Silence

A tower of silence, or dakhma, is a funerary structure used by people of Zoroastrian faith. It is a practice of disposing of the dead by exposing the bodies to the Sun and vultures. According to Zoroastrian belief, the four elements (fire, water, earth, and air) are sacred and should not to be polluted by the disposal of the dead through cremation and burial. In order to avoid polluting these elements, Zoroastrians expose the corpses to scavenging animals. The towers of silence are raised platforms with three concentric circles within them. The bodies of men are arranged on the outer circle, those of women in the middle circle, and those of children in the inner circle. The vultures can then come and eat their flesh. The remaining bones are left to be dried and bleached by the Sun before being deposited in an ossuary. These towers can be found both in Iran and India.[7]

3 Skull Burial

Kiribati is an island nation in the Pacific Ocean. In present times, its people practice mostly Christian burials, but this was not always the case. Before the 19th century, they practiced what is called the skull burial, in which they kept the skull at home so that the native god could welcome the deceased’s spirit to the afterlife. After someone died, their body would stay at home for three to 12 days for people to pay their respects. To make the body smell nice, they would burn leaves near it and put flowers in the corpse’s mouth, nose, and ears. They could also rub the body with coconut and other scented oils. A few months after the body was buried, family members would dig up the grave and remove the skull, polish it, and display it in their home. The deceased’s widow or child would sleep and eat next to the skull and carry it with them wherever they went. They could also make necklaces out of the fallen teeth. After several years, they would rebury the skull.[8]

2 Hanging Coffins

People of the Igorot tribe of Mountain Province in Northern Philippines have been burying their dead in hanging coffins, nailed to the sides of cliff faces, for more than two millennia. They believe that moving the bodies of the dead higher up brings them closer to their ancestral spirits. The corpses are buried in a fetal position, as the Igorot people believe that a person should leave the world the same way they entered it. Nowadays, younger generations adopt more modern and Christian ways of life, so this ancient ritual is slowly dying out.[9]

1 Sokushinbutsu

Many religions from around the world believe that an imperishable corpse conveys an ability to connect with a force beyond the physical realm. The Japanese Shingon monks of Yamagata took it a step further. Their practice of self-mummification, or sokushinbutsu, was believed to grant them access to Heaven, where they could live for a million years and protect humans on Earth. The process of mummifying themselves from inside out required utmost devotion and self-discipline. The process of sokushinbutsu started off with the monk adopting a diet consisting of only tree roots, barks, nuts, berries, pine needles, and even stones. This diet helped eliminate any fat and muscle as well as bacteria from the body. It could last anywhere from 1,000 to 3,000 days. The monk would also drink the sap of the Chinese lacquer tree, which would render the body toxic to insect invaders after death. The monk continued with the meditation practice while drinking only small amounts of salinized water. As death approached, he would rest in a small, tightly cramped pine box, which would be buried. The corpse would then be unearthed after 1,000 days. If the body had stayed intact, it meant that the deceased had become sokushinbutsu. The body would then be dressed in robes and put in a temple for worship. The whole process could take more than three years to complete. It is believed that 24 monks successfully mummified themselves between 1081 and 1903, but this ritual was criminalized in 1877.[10]