There is still something almost unbelievable about the scale of these beasts. We have only just begun to learn about this mysterious creature, and the island of Komodo may yet yield more secrets.

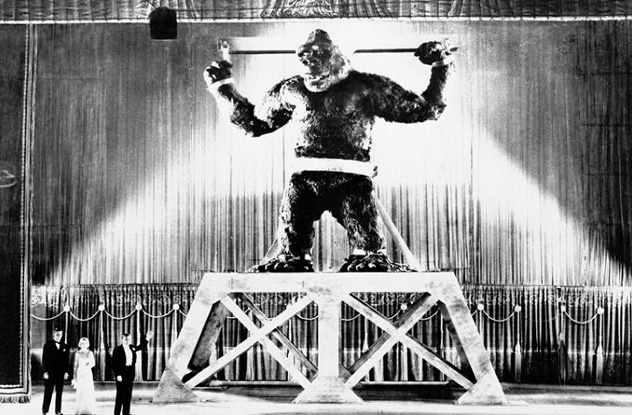

10 Inspiration For King Kong

Merian C. Cooper conceived of King Kong as the story of a giant gorilla on a prehistoric island, and he imagined the film ending with the beast on top of the Empire State Building. He didn’t know, however, how to get from the premise to the climax—until he turned to Douglas Burden and his Komodo dragons. Burden was known for capturing live Komodo dragons and bringing them to New York. The first two living dragons that made it back to the United States did not survive long. Cooper blamed civilized society for the deaths of the dragons in the zoo, and he decided he wanted his furry monster to similarly get captured, be showcased, and die. This doesn’t mean the filmmakers were huge advocates of animal welfare. Originally, they were so inspired by the dragons that they wanted a real one to fight a live gorilla on film. The logistics of this turned out to be way too much work, and the idea was scrapped.

9 Septic Bite Myth

Many say that the Komodo dragon’s bite is ridiculously infectious. Its saliva supposedly contains horrible bacteria that will melt your insides, and if you’re too big to kill directly, it will just bite you and then wait for the germs to finish you off. Australian researcher Bryan Fry was skeptical, and his research recently proved the septic bite to be a myth. He found that the bite alone is no more likely to cause infection than any other wild animal’s. Instead, dragons kill their prey with powerful venom. Once the fearsome predator latches onto a victim with its teeth, it thrashes swiftly while digging in hard. This releases the venom from tiny mouth ducts, quickly subduing smaller animals. For larger prey, it may wound them and leave just as the myth says, but venom rather than bacteria finishes the job.

8 They Love To Climb

Most people at the zoo only ever see adult Komodo dragons, so it’s kind of hard to imagine them as little things. Yet they start out, like most babies, as miniature versions of the real thing. While the adults often spend their time in burrows, out of the heat, the little ones prefer to stay up in the trees until they fully mature. Due to their sharp claws, they are naturals at climbing and will spend a lot of time up in the trees for the first few years of their lives. The little ones don’t join their parents in the burrows because Komodo dragons are cannibalistic and will eat their babies if nothing else is available—or just if they feel like doing so. Adults find it harder to make their way up the taller trees as they get bigger and heavier. So if you are on an island with these monsters, you may be able to escape up a tree to get away from a big one, only to run into a whole bunch of other dragons of various sizes, waiting to feast on your flesh.

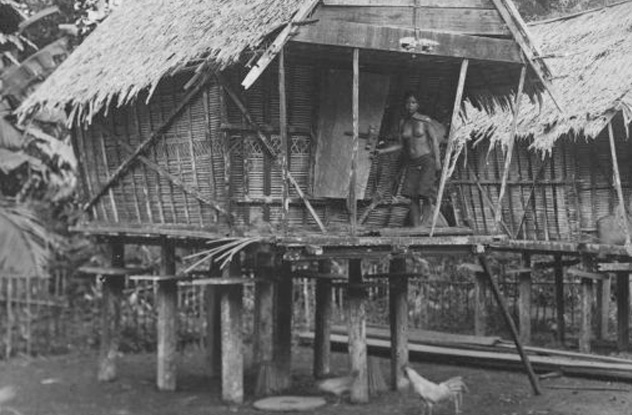

7 Aggressive Grave Robbers

The Komodo dragon is an enormous monitor lizard, and monitor lizards are known for enjoying eating corpses, including human ones. In some parts of the world, this was considered less than desirable, and in Komodo, people put rocks over shallow graves to protect remains from dragons. However, in Bali, some tribes are alleged to have once gotten rid of their dead by having the monitor lizards eat them. Perhaps it’s eating so many corpses that gave these lizards their taste for human flesh. While some claim they’ll only attack you if you venture into the wild, dragons have been known to wait outside people’s homes to strike. One man barely survived after a dragon climbed the ladder to his house—which was protected by stilts, like many houses on the islands—and attacked him without provocation.

6 Hard Of Hearing

While Komodo dragons are capable of hearing, they have little use for the sense when hunting, since they can’t hear lower- or higher-pitched sounds. Also, while the Komodo dragon can see all right, it only has cones—humans have both rods and cones—and so it sees less well at night. Since the dragon only has passable sight and poor hearing, it relies almost entirely on smell for hunting. However, unlike humans and many mammals, it doesn’t use a traditional nose for its olfactory needs. The dragon uses a vomeronasal, or “Jacobson’s organ,” which is often associated with identifying pheromones in the air. The tongue also gets samples of the air’s chemical concentration, and the Jacobson’s organ tells the snake where and what his prey is.

5 Disgusting Defense Mechanisms

As we’ve mentioned, being a baby Komodo dragon is pretty hard work. Apart from just generally surviving, it also has to watch out for adults from its own species turning it into a quick snack. To avoid getting outright cannibalized when not hiding in the trees, the baby Komodo dragon will cover itself in feces, knowing the smell will repulse adult dragons. This allows the little guy to hide near a killed animal’s intestines, camouflaged in dung, waiting for a chance to take some meat for itself. One day, the little monster will reach full size himself and terrorize another generation of Komodos.

4 Parthenogenesis

If you’ve ever watched Jurassic Park, you remember that the all-female dinosaurs there manage to reproduce. Upon discovering this, Dr. Malcolm famously quips that “life finds a way.” The Komodo dragon, also isolated on remote islands, similarly evolved the incredibly rare skill of parthenogenesis, which lets females reproduce without males. This was only discovered as recently as 2006. When there’s no male around, the female can make an unfertilized egg into an embryo. The spawn will always end up being male, and this suits the lizard fine, because it can then mate with its own child. This process is well known in lower organisms, such as aphids, but it’s almost unheard of in animals so complex as the Komodo dragon. One other higher animal recently discovered to use parthenogenesis is the hammerhead shark.

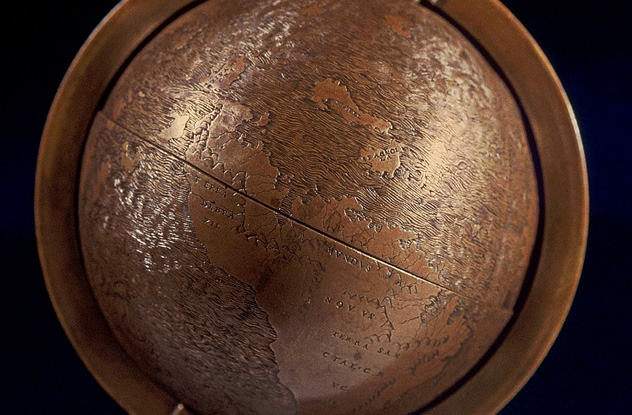

3 Here Be Dragons

A commonly held belief is that in the olden days of map making, explorers would draw a dragon or sea serpent to indicate unknown dangers, along with the Latin phrase “Hic sunt dracones,” which translates to “here be dragons.” However, no evidence says that this was actually a common convention. Only a small number of maps have been found that use dragons as symbols of warning, and the few labeled “here be dragons” all copy a single example, known as the Hunt-Lenox globe. This one map places the words quite near the islands where the Komodo dragon makes its home. This has led some historians to believe that the original phrase may have indeed been a warning about the vicious monsters. In that case, the admonition is not a warning about the dangers of the unknown but a literal warning to watch out for dragons.

2 The Legend Of The Dragon Princess

The villagers who live alongside the Komodo dragons have developed a strange relationship with the monsters. Although attacks have been publicized more in recent years, and there are some claims that they are increasing, those who live with the dragons have long found them an almost endearing part of their ecosystem. An old Indonesian legend shows just how romantically the creatures are viewed. In the legend, a man falls in love with a dragon princess. They are gifted with twins, one a Komodo dragon girl (whom the parents name “Orah”) and the other a human (whom the parents name “Gerong”). The two are split up between their parents and each grows up without knowledge of the other. One day, Gerong is out hunting in the forest when he comes across a powerful dragon. He is about to take it out with his spear, when his dragon princess mother appears and tells him he is about to make a shish kebab out of his own twin sister. He spares the life of his lizard sibling, and they live happily ever after.

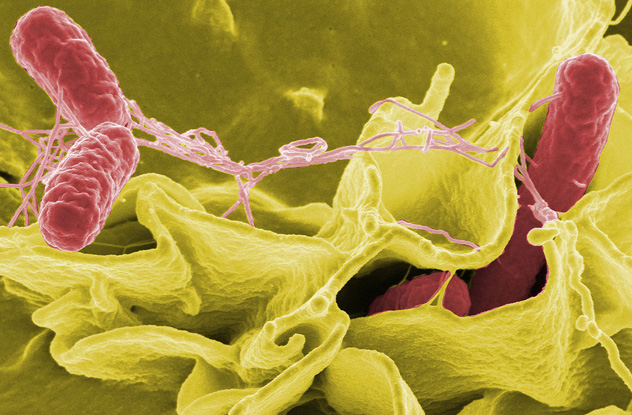

1 The Spread Of Salmonella

In 1996, quite a few people who visited the Denver Zoo on the same day ended up infected with salmonella. Fifty people got ill, and eight of them ended up in the hospital. The CDC easily identified the disease as a strain carried by one of the Komodo dragons at the zoo. The zoo had a special exhibit that day with the Komodo dragon out of its usual glass cage, so that people could see and interact with it better. They’d moved the animal to a new, open wooden cage. People touched the wood that had touched the dragon—who had been in contact with its own contaminated feces—and soon became very sick. While this may seem like a freak occurrence, it shows how important it is that exotic animals are handled with care. If the disease the dragon had spread was not just a common strain of salmonella, things could have been much worse.