Unusual authors or unknown works by famous figures are just the beginning. Recent finds also included books that kill, Bible stories with different endings, and one of the biggest scams to hit the antiquities trade.

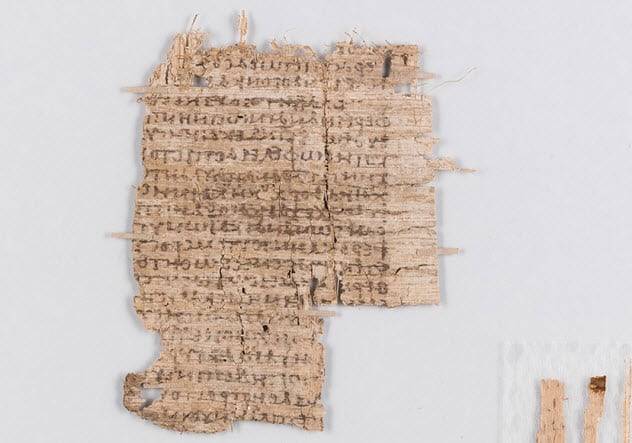

10 Ancient Egyptian Medicine

A unique collection of Egyptian manuscripts are held in Copenhagen, Denmark. The large cache only came up for translation in 2018, and thus far, the fraction deciphered was insightful. Several medical texts came from the ancient Tebtunis temple library, which was active until 200 BC and founded long before the famous library in Alexandria.[1] One spoke about human kidneys, soundly smashing scholars’ belief that Egyptians of the time were not aware of the organs. Another dated to around 3,500 years ago, when no European writing existed. It described a specific pregnancy test which later reappeared as a German remedy recorded in 1699. This highlighted the millennia-strong influence of ancient Egyptian medicine, which is often forgotten in the face of the great Greek and Roman texts. Ironically, Egyptian knowledge was the root of most of their work. The Copenhagen collection also touched on astrology, botany, and more. This is a bonanza for researchers interested in the true history of science.

9 Galen’s Hysterical Diagnosis

In the past, physicians believed that a woman’s womb could “wander” and resulted in hysteria. Where it supposedly traveled was never explained, but one Roman doctor did not support this view. His name was Galen (AD 130–210). This celebrated physician’s work was the cornerstone of what would later become modern medicine. However, a new discovery showed that even Galen got things wrong. Badly, in this case. It all started with a 2,000-year-old papyrus that nobody could read for four centuries. The text on both sides included what looked like mirror writing. With the papyrus hidden away in a Swiss university’s archive, conservationists only managed to clean the damaged document in 2018. The backward writing turned out to be no mystery. The document was comprised of several papers stuck together, some the wrong way. The riddle of its contents was finally solved as an unknown work by Galen or somebody who described his diagnosis on hysteria. The writing claimed that the affliction was triggered by too little sex. Galen thought that women could suffer from “hysterical suffocation,” or apnea, as a result. Bizarrely, he described the occurrence of suffocation, spastic, and apnoic symptoms to appear “on the affected parts.”[2]

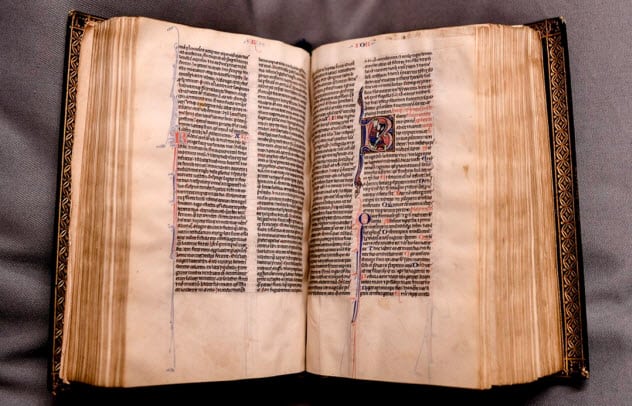

8 Rare Bible Recovered

Countless holy relics and books went missing during the reign of Henry VIII. The English monarch ruled in the 16th century, during which he shut down most monasteries. One of them was Canterbury Cathedral. During this crisis, its vast library of 30,000 books disappeared. In 2018, the institution was reunited with one lost volume—a rare medieval Bible. By the time King Henry destroyed the monasteries, the pocket-size book was already 300 years old. Half a millennium later, the so-called Lyghfield Bible showed up at a rare book sale in London. Using grants and donations, Canterbury Cathedral bought it for £100,000 (about $130,000). Written in Latin and beautifully decorated, it is the only Bible in the cathedral’s medieval collection and one of 30 books from the original library. Along with the other ancient volumes, the Lyghfield Bible is now on the UNESCO UK Memory of the World Register.[3]

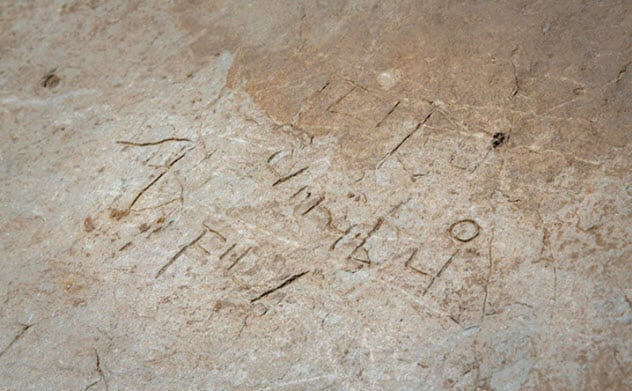

7 A King’s Fear

King James I of England had a special fear, and hundreds of his subjects died as a result. James was scared of witches. In 1606, his treasurer, Thomas Sackville, expected a visit from the king. Sackville installed magnificent rooms in the tower of his house, called Knole. Unknown for centuries, he also took measures to protect the royal from witches. In 2014, conservation efforts at Knole revealed symbols designed to stop witches from reaching the king’s chambers. They were under the floorboards and joists and around the fireplace. The latter was considered a favorite way for witches to enter. The marks included carvings and scorched designs resembling Vs and Ws, which were meant to attract the protection of the Virgin Mary. To catch malevolent spirits, there were also mazes called demon traps. These are history’s first accurately dated witch marks. Tree rings showed that the timber was cut in 1606, and the supernatural script was added just before installation. They also squashed an old suggestion that the scratches were nothing but carpenter measuring lines. Knole’s beams carry both symbols and separate builders’ marks.[4]

6 Evidence Of King Arthur

Proof of King Arthur’s court was found in Cornwall but only for believers in the legendary ruler. For the rest, the 1,300-year-old artifact proves nothing. In 2018, conservationists found a stone at Tintagel Castle, the traditional birthplace of King Arthur. For centuries, the site was scoured for any leads that could prove his existence. The slab added an interesting detail to the case. It may not say “Arthur was here,” but the 0.61-meter-long (2 ft) windowsill was engraved by an educated hand. Latin phrases, Christian symbols, and Roman and Celtic names were all carved by a scribe familiar with the illuminated Gospel manuscripts of the time. For researchers, who knew the place held high status in the past, the level of education was a pleasant surprise. At the very least, it showed that Tintagel’s community was highly cultured and not medieval barbarians. This paves the way for the famous monument’s possible confirmation as a royal site.[5]

5 Oldest Library In Germany

In 2018, archaeologists from Cologne excavated an old Protestant church. While clearing the area, the team found ruins underneath. The ruins were not a surprise, after all, the area has been continually inhabited for over 2,000 years. The Romans themselves founded the city of Colonia on the Rhine in the year AD 50 and made it their center of government by AD 85. However, the purpose of the structure was not so obvious. An early suggestion that the building housed public gatherings was challenged by the unusual walls. Roman meeting places are not known for including strange cavern-like spaces. It took intensive investigations and comparing the walls to other ancient buildings before a match was found. The same walls turned up at the Ephesus in Turkey, which came with a known library. For this reason, archaeologists now believe that the foundations belonged to Germany’s oldest library. Built during the second century, it also likely stood two stories high and covered an area of 20 meters (65 ft) by 9 meters (30 ft). Described as a truly spectacular discovery, the ruins’ cases and niches once stored around 20,000 parchment and papyrus rolls.[6]

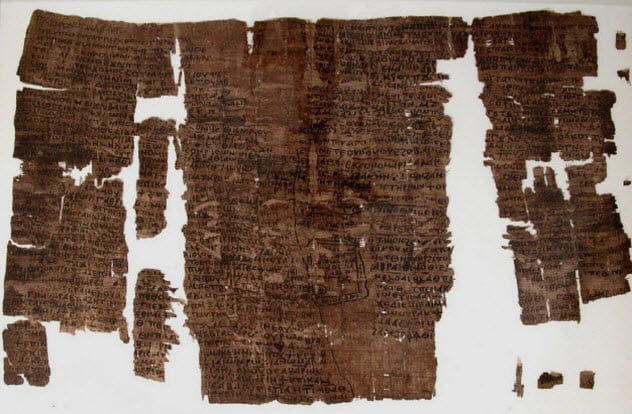

4 A Different Biblical Tale

For decades, an Egyptian papyrus sat forgotten at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. In 2018, researchers had another look at the artifact. All that was known about the piece was that it was found in 1934 near Pharaoh Senwosret I’s pyramid. It was about 1,500 years old and never deciphered. The renewed scientific interest paid off. After a thorough examination, the paper turned out to be written during a period when Christianity was practiced in Egypt. The papyrus contained magical incantations, some invoking God. A curious title for God was “the one who presides over the Mountain of the Murderer.” Though the papyrus does not mention the New Testament, it names several people from the Hebrew Bible. For this reason, researchers linked the title to an incident in the Book of Genesis when God ordered Abraham to sacrifice his son, Isaac, on Mount Moriah. Genesis says that God prevented Isaac’s death, but the papyrus describes the story in a manner that indicates Isaac was sacrificed. Interestingly, it is not the first ancient text that claims Abraham murdered his son.[7]

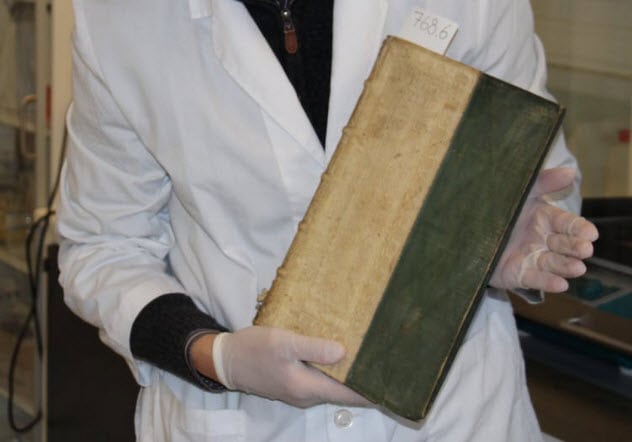

3 Poisonous Schoolbooks

In 2018, the University of Southern Denmark perused their school’s library for Renaissance-era books. Bookbinders of the time considered older parchments as waste and used them to dress new books, but they are gold to scientists. Three manuscripts were chosen from the rare books collection. To see if their covers were made from recycled documents, each was examined under a special X-ray microscope. Looking with the naked eye was useless because the trio came thickly layered with green paint. The idea was to use fluorescence to make hidden ink detectable. Instead, something else glowed and the implications were frightening. The radiance came from the green paint or, more correctly, betrayed the presence of arsenic. Green pigment was a Victorian folly. Stiff amounts of arsenic were used to create a popular color called Paris Green, which was used everywhere. As a result, Victorians wore toxic dresses, licked arsenic-laced postage stamps, and lived in houses with poisonous green wallpaper. This deadly toxin does not lose its potency over time, cannot be tasted, and has no odor. Another frightening fact, especially for those who handled the three books, arsenic can be absorbed through the skin.[8]

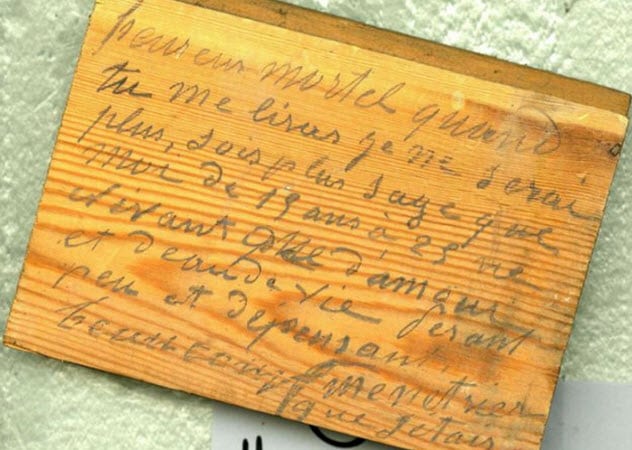

2 Secret Floorboard Diary

When an old French Alpine chateau was renovated in 2018, an upper room’s floorboards were removed. Amazingly, writing was discovered on the underside. The author identified himself as 38-year-old Joachim Martin from the village Les Crottes. In 72 penciled entries, dating 1880 and 1881, Martin described many things about himself. This gave an incredibly rare insight into 19th-century village life. While working on the chateau as a carpenter, the married Martin wrote about the trouble that couples had with a lecherous priest who pried into bedroom affairs. He also recorded a haunting secret: He knew that his childhood friend Benjamin had six children by a mistress and that four were murdered by their father. Martin wrote frankly, describing things of which he could not speak openly. One entry explained why. He knew that he would be long dead by the time anyone found his memories. Joachim Martin really existed. After the discovery of the wooden diary, researchers tracked down when he lived (1842–1897), that he had four kids, and that he played the fiddle. A letter he wrote asking to have the lecherous priest replaced was also found later.[9]

1 Dead Sea Scrolls Scam

There is a profitable buyer on the antiquities market—the wealthy evangelist. One thing wanted by these hard-core collectors is a rare fragment of the Dead Sea Scrolls. The tomes contain sections of the Hebrew Bible which are over 1,000 years older than other sources. This made the scrolls an electrifying find and is one reason why these evangelists pay millions for a tiny scrap. However, a desperate rich buyer also attracts scam artists. In 2017, experts warned that the majority of the fragments in circulation are potential fakes. In fact, they fear that 90 percent of the 75 fragments that have changed hands since 2002 are forgeries. Some pieces have glaring mistakes, like “ancient” dirt found under the ink and writing made to snugly fit inside a fragment. (Real pieces show broken words sheared from a larger page.) The author was not a professional scribe but wrote as if he copied something.[10] The biggest problem, however, is the buyers. Most are so dazzled by the idea of owning fragments that they refuse to believe that they were swindled or question why the market conveniently keeps churning out more. Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages