10 El Chapo’s Escape

The Mob Museum in Las Vegas, Nevada, features a diorama showing Sinaloa Cartel chief Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman’s escape from prison. Model makers Shawn Bicker and Adam Throgmorton spent six weeks constructing the scaled model of the prison. The diorama includes guard towers, the wall, a fence topped with razor wire, and a cutaway view of the shower in El Chapo’s cell and the tunnel beneath it, which led the prisoner to a waiting motorcycle and his short-lived freedom. The diorama’s tunnel connects the drug lord’s shower to a construction site building, which stood 1.5 kilometers (0.9 mi) away from the prison.

9 Henry Ford’s Monkey Bar

On a dais in a tavern, a monkey plays a piano, accompanied by a monkey harpist and a monkey violinist, while other primates scan music sheets or sit at tables, enjoying the music. Three brass monkeys atop the piano’s lid are posed in see-no-evil, hear-no-evil, and speak-no-evil poses. A well-stocked bar, a cabinet full of pigeonholes, and a billiard table furnish the crowded tavern, standing on the hardwood floor that unites the elements of the strange tableaux. The monkey bar diorama is one of several created by Patrick J. Culhane, who was then an inmate at the Massachusetts State Prison at Charlestown. While serving a sentence for “larceny from a conveyance,” Culhane carved elaborate, detailed dioramas from a variety of materials. He intended his work to illustrate the folly of engaging in vices such as drinking, smoking opium, and gambling. Culhane presented his monkey bar diorama to Henry Ford, who hired him after he served his sentence. Ford may have helped to secure Culhane’s release from prison.

8 The Death And Burial Of Cock Robin

Brooklyn’s Morbid Anatomy Library and Curiosity Museum was once a treasure trove of the bizarre. Among its many curious pieces was taxidermist Walter Potter’s macabre diorama, The Death and Burial of Cock Robin, which was inspired by an English nursery rhyme. Created around 1861, the display shows a pair of avian pallbearers dressed in ribbons carrying the blue coffin of Cock Robin, who is visible through the glass lid. Each side of the coffin is studded with metal rivets and bears three handles. Atop the lid, a spray of flowers and a framed picture accompany the deceased to his final resting place.

7 ‘Die-o-Ramas’

A former crime reporter and investigator for the federal public defender in Las Vegas, Abigail Goldman creates series of “Die-o-Ramas” to tell the story of murder and death. The results are horrific, showing murder by lawn mower, a tiger mauling, a decapitation, and other dastardly deeds. At 1:87 scale, the dioramas are housed inside Plexiglas boxes ranging in sizes from 26 square centimeters (4 in2) to over 1 meter (3 ft) long. Some of the larger ones show a shark attack, a shooting, a poolside murder, and a picnic featuring a dismembered corpse as the entree. The smaller works include men drinking beer as they barbecue a butchered human corpse, the discovery of a body in a park, and a woman hanging a murder victim’s torso on a clothesline, along with the day’s laundry.

6 Apocalyptic Tableaux

Lori Nix’s art occupies a unique niche. Working from as many as 20 images, she and her partner Kathleen spend months creating extremely detailed, realistic dioramas displaying scenes of an eerie, post-apocalyptic future devoid of any trace of human beings except the artifacts of civilization left from before nature began to reclaim the world. In Library, a 2007 work, trees intrude on an abandoned library, stretching their limbs above overturned chairs, fallen books, and debris, while hundreds of bound books occupy shelves, awaiting readers who will never return. Subway (2012) shows a train’s car, its ceiling rusted, its walls corroded, and its floor covered with drifts of sand, out of which grow desert plants. Through the missing door, beyond the barren landscape, the smog-enshrouded skyline of a deserted city rises, forlorn in the distance.

5 Fish Head Figures

One might imagine fish heads would be rather inexpressive, but that’s not the case for the fish heads that French artist Anne-Catherine Becker-Echivard uses to create the protagonists of her dioramas, a series called Les Temps Modernes (Modern Times). The aim of her dioramas is to represent the “absurd realities of modern life,” which she takes to “a farcical level of comedy.” She often spends months to create a single diorama. She purchases fish at a local market, decapitates them, keeps the bodies for meals, and mounts the heads on human figures. The contrast between the “human” bodies and the fish heads is startling and absurd, just as Becker-Echivard intends. In one diorama, while wrapping chocolate, a production line worker has accidentally cut a piece in half and is being reprimanded by his supervisor. The worker looks properly abashed, while the supervisor’s anger is readily apparent as he scowls at his unfortunate employee. In another diorama, a fish man in a blue beret stands before an expressionistic oil painting mounted on a gallery wall, his chin resting on his hand, as he studies the work of art. His down-turned mouth suggests, perhaps, that he doesn’t think much of the masterpiece.

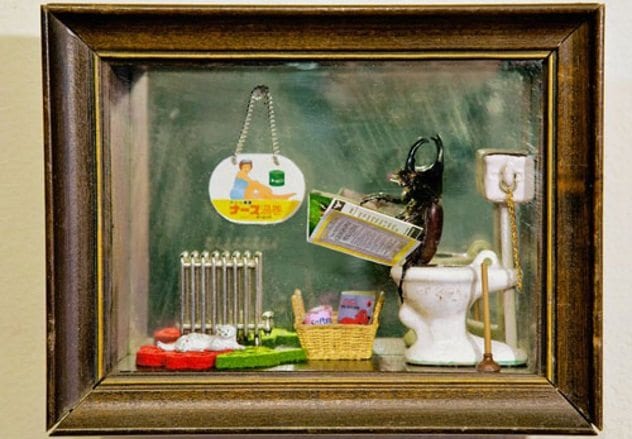

4 Bug Displays

Entomologist Daisy Tainton puts her knowledge of bugs to good use in creating her insect dioramas. She has also taught classes at the Morbid Anatomy Library, showing students how to create their own bug-infested displays. She provides an overview of the course content: “We walk people through steaming, softening, and repositioning them, and then you have to create an armature to pin them and dry them in the position you want.” Her own dioramas focus on “domestic scenes.” A beetle knits, seated in a rocking chair beside a cabinet displaying knickknacks. The room is comfortable, a papered wall bearing a mirror and a framed picture of another bug (perhaps a relative). The beetle’s children assist her, holding her spool of yarn. Another diorama displays a dung beetle reading a newspaper as it sits on a toilet, answering nature’s call. The bathroom is heated by a radiator; a basket of magazines sits on the floor, and a cat stretches out on a pallet by the door.

3 Helicopter Crash Site

In 1993, as he was returning home in a rainstorm from his dig on the east side of the Potomac River, archaeologist Frank Owens spied a helicopter. Later the same morning, he saw the aircraft, Marine Helicopter Squadron One’s flight Nighthawk 18, again. It had crashed, and its pilot, Major William S. Barkley, Jr., who had transported Presidents George Bush and Bill Clinton, lay with his four crew members, all of whom were dead or dying. According to the Marine Corps, Barkley was investigating a previous pilot’s report of “engine over-speeding during autorotation” when the aircraft crashed, but Owens said the crash site looked suspicious, and he believes a government cover-up of the incident may have occurred. According to Owens, the helicopter “was shot down by a Star Wars-type energy beam fired from a secret military installation engaged in experimental testing of electromagnetic pulses.” As a result of his experience, Owens has constructed a diorama of the crash site, which sits in a corner of his home office, markings indicating the locations of the pilot’s and crew members’ bodies.

2 Taxidermic Exhibits

At the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, DC, dioramas have become extinct. When the last full-time taxidermist retired, he wasn’t replaced, and in 2003, the museum decided to discontinue, dismantle, and discard most such displays. Others were given to other museums’ collections. In their day, however, the museum’s large dioramas brought scenes to visitors who might otherwise never have seen such sights as a pride of East African lions “living” in the wild, pumas standing or reclining against a backdrop of snowcapped mountains, elk walking amid the trees of a forest, a hippopotamus in the African savanna, or a walrus on an iceberg. Many of these dioramas were created by a team of taxidermists, zookeepers, and assistants in the taxidermists’ laboratory behind the Smithsonian Institution’s building. One of the taxidermists, William Temple Hornaday, was also a big game hunter, and after one of his expeditions, he personally supplied the buffalo for a diorama he created.

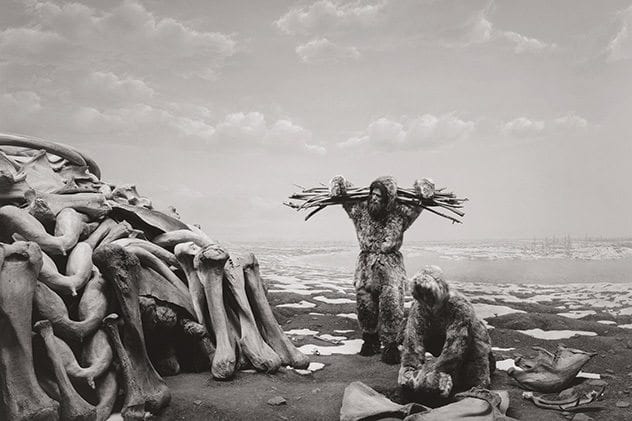

1 Photographic ‘Dioramas’

If, for some, dioramas are going the way of the dinosaurs, Japanese photographer Hiroshi Sugimoto has dedicated himself to preserving their memories. For the past 40 years, he has taken black-and-white photographs of the dioramas in natural history museums. To enhance their lifelike appearance, he films the displays “as if they were real, omitting the framing wall, avoiding glare and reflections,” and eliminating any other suggestions that the scenes are anything less than authentic. He explains what led him to his obsession: While visiting the American Museum of Natural History in New York, he was struck at how “fake” the dioramas looked, but, when he took “a quick peek with one eye closed, all perspective vanished, and suddenly they looked very real. [He’d] found a way to see the world as a camera does.” He’s been shooting realistic “dioramas” ever since, including vultures gathering to feast on carrion, gorillas in the wild, and a forest overlooking a cliff rising from a mist-shrouded sea. Gary Pullman lives south of Area 51, which, according to his family and friends, explains “a lot.” His 2016 urban fantasy novel, A Whole World Full of Hurt, was published by The Wild Rose Press. An instructor at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, he writes several blogs, including Chillers and Thrillers: A Blog on the Theory and Practice of Writing Horror Fiction and Nightmare Novels and Other tales of Terror.