An accused raises the defense of necessity when he or she alleges that the alleged act was carried out due to exceptional circumstances. The accused was truly desperate and had no choice but to disobey the law. Courts have generally recognized a set of criteria to determine whether or not the defense can be met, as follows: 1 The unlawful act was intended to avert a greater evil 2 There could not have been any reasonable, legal alternative course of action 3 The unlawful act could not have been more than what was necessary to avert the greater evil and 4 The unlawful act must have been effective, or at least highly probably effective, towards averting the greater evil. However, courts are generally very reluctant to accept this defense, due to fear of precedent and public message. Therefore, it could be possible for an accused to be convicted, even where all of the above criteria hold.

The accused alleges that he or she committed the offense under compulsion by a person to commit it, where the compulsor was threatening death or bodily harm toward the accused, or a third party, for noncompliance. In most societies, the defense can only be used if the threats were of greater severity than the offense committed, and the threats were immediate and otherwise unavoidable, and were threats of bodily harm or death. Some countries, such as Canada, have some offenses that are entirely exempt from this defense.

The accused alleges that he or she had lack of control over their actions, and, therefore, cannot be held responsible. The accused may have been deluded, incapacitated, provoked, severely mentally disabled or even have been sleepwalking. In general, they were in a state of mind in which they did not have control over their actions, didn’t know what they were doing or were unable to understand that what they were doing was wrong, or illegal. Many courts distinguish between insane automatism and non-insane automatism. For insane automatism, the court usually refers the accused to psychiatric, or other appropriate care. For non-insane automatism, the court either acquits the accused or gives a more lenient sentence.

This defense is mainly used in charges of assault or homicide. The accused claims to have assaulted, or killed, the victim because the victim attacked the defendant. In cases where the accused actually killed the attacker, the court must establish that the attacker would have otherwise killed the defendant, and the defendant could not have otherwise avoided his or her own death. In any case, the attack by the accused could not have been more than what was necessary to ward off the attack of the original aggressor.

The accused was unaware of a fact that would have made the alleged action illegal. While ignorance of the law itself is not a defense in most jurisdictions, ignorance of the fact may be a defense. For example, a bartender could have a defense for serving an underage customer, where the customer presented counterfeit ID, if the court feels it was reasonable for the accused to believe the customer was of age. However, a person from the general public would not have a defense if they gave a minor alcohol because they thought the legal drinking age was lower than it really was. Similarly, there exists a defense of accident, in which the accused did not intend to do what they did. The accused’s sleeve may have caught on a fire alarm and they pulled it unintentionally, or a doctor may have mistakenly sent a phone message to the wrong number by mistake, in which the message contained some confidential information of the patient.

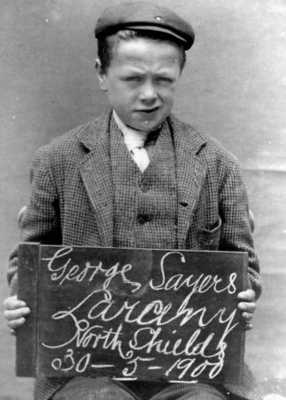

Many jurisdictions have what is known as The Age of Criminal Responsibility. If a person commits an offense while they are younger than that age, they cannot be held legally responsible for their actions. An accused might claim that they were younger than the age of criminal responsibility when they committed the alleged act, and therefore cannot be held accountable.

The accused was restrained by external forces, which rendered them incapable of controlling their own actions. Some examples might be a driver being pushed by a hurricane or landslide, in which they were unable to stop at the scene of an accident, or a person being tied to a pole, while others poured illegal drugs down the accused’s throat.

The accused committed the offense out of deception by an official or authority or, in some cases, an ordinary person disguised as an official or authority. An official may have convinced or deceived the accused into thinking that what they were doing was not illegal, or was necessary for justice, science or another legitimate field. For example, a police officer may have instructed the accused to import heroin into California claiming there was a scientist there who could test it for chemical compounds which could cure cancer.

Some laws may contain a phrase that says something like “For a sexual purpose” or “For a fraudulent purpose” or “With intent to (do whatever)”. The accused claims they did not commit the act for that purpose and, therefore, are not in breach of the law. The defense is only acceptable where the law stated a purpose, and the court feels convinced the accused did not commit the act for the illegitimate purpose stated.

A person can be tried for an offense only once, whether they were acquitted or convicted at their trial. If a person is tried for an offense in a manner which is not an appeal of the original hearing, the accused can claim double jeopardy. This includes prosecuting the same action under the name of a different charge. Similarly, a person cannot be charged with a new offense if their action was not yet illegal at the time it was carried out.

I have made this item a bonus as it is an extremely rare and unlikely defense. When an accused raises the defense of legal conflict, or sometimes called legal dilemma, they claim that no matter what they did or didn’t do, they would have been in breach of some law. In short, they were in a completely inescapable legal checkmate and a law would have been against them no matter which way they turned. Usually, such a situation is a result of the people making the legal code of the jurisdiction not thinking clearly or holistically. It differs from the defense of necessity in that, in the defense of necessity, the legal course of action is undesirable, but in the defense of legal conflict, there is no legal course of action at all. For example, there have been numerous cases in Asia, where raped, married women have been charged with adultery, but if they defended themselves against their aggressors they could, (and have in some cases, such as Nazanin), be charged with assault or murder. In Canada, I have personally noticed one hole in the law, that could bring this defense about. It is an indictable offense, punishable by imprisonment for life, to fail to disperse from a riot zone, declared under a proclamation reading. But what if a person ran someone over just as they were driving out of the zone? If they helped the person, they could face charges for failure to comply with the proclamation, but if they left the riot zone, they could be charged with a hit and run. Courts have been known to accept this defense if they recognize that the accused had no legal way out of the situation, and the accused took the path of the least serious legal breach. Such an acquittal often results in amendments to the code to ensure the situation does not happen again.