10 The Syrian Coup D’etat

The extent of US involvement in the bloodless coup which overthrew the secular democracy that had sprung up in Syria after World War II has been disputed ever since. The popular opinion is that in 1949, the CIA decided their best bet to further US interests in the area would be to “encourage” a coup d’etat in the country.[1] A proposed construction project, the Trans-Arabian Pipeline, was in danger of not being built under the rule of Shukri-al-Quwatli, and if there’s one thing that gets America’s goat, it’s being denied oil. Therefore, a shyster named Husni al-Za’im (pictured above), convicted less than a decade earlier for graft, was propped up by the CIA, and he led an overthrow of Syria’s democratically elected president. Almost immediately, the pipeline plans were approved, as were a number of pro-American initiatives, such as peaceful negotiations with Israel. (The First Arab-Israeli War had just ended the year before.) However, just four months after he assumed power, al-Za’im himself was deposed, shot by a strongman who managed to rule for about five years before he was deposed as well. Nearly two decades of coup after coup ensured, until Hafez al-Assad took power and reigned for 30 years before his death.

9 Operation PBSUCCESS

Like a number of others, the US-orchestrated regime change which took place in Guatemala in 1954 happened because Communism was supposedly gaining a foothold in the country. The second democratically elected president of the country, Jacobo Arbenz, instituted a number of land reforms, populist actions meant to improve the lives of the poorest Guatemalans. The CIA didn’t feel the same way and almost immediately put a target on his back. “Target” can be interpreted both figuratively and literally; assassination was an option up until Arbenz resigned. In addition, United Fruit, a US company which held quite a bit of land in Guatemala, suffered under the reforms, mostly due to the ending of their exploitative labor practices, and they lobbied the US government to intervene. Operation PBSUCCESS, a plan for “psychological warfare and political action,” was authorized by President Eisenhower in 1953.[2] In addition, the CIA trained and funded a paramilitary group led by Castillo Armas, which attempted to violently overthrow Arbenz, though they met with a number of setbacks. The threat of US intervention, thanks to the propaganda which was part of Operation PBSUCCESS, was enough to force Arbenz’s resignation. Ten days later, Armas took power, instituting four decades of authoritarian rule which decimated Guatemala’s Maya population, thanks to near-continuous and bloody civil war. The coup was widely reviled by the international community, with some comparing the Americans to “colonialists” or “Hitler speaking about Austria.”

8 Operation Urgent Fury

Grenada is a small island in the Caribbean, only 640 kilometers (400 mi) south of Puerto Rico, and as the locals say: It’s “just south of paradise, just north of frustration.”[3] For President Reagan, it was a constant frustration, with Marxists having controlled the country since the onset of his presidency. In 1983, fed up with what they deemed insufficiently radicalized behavior, members of the ruling party executed their leader, replacing him with Hudson Austin, a general in the People’s Revolutionary Army. This was the straw that broke the camel’s back for the Americans, and plans were quickly drawn up to invade the island. Troubles started immediately, creating problems which would last for much of Operation Urgent Fury, as the various branches of the military couldn’t agree on what to do. In the end, over 7,000 troops were landed in Grenada, with a number of different goals to achieve, chief among them being the removal of the current regime. (The rescue of American students in the country was used as an excuse for the invasion.) Faced against the might of the US military, Austin’s government quickly folded and was replaced by pro-US leadership. When asked about the nearly unanimous international outrage concerning the invasion, Reagan simply replied, “It didn’t upset my breakfast at all.”

7 The Iraq War

The invasion which introduced the world to the idea of “regime change,” the Iraq War began in 2003 under the auspices of removing Saddam Hussein from power, as he was alleged to possess a number of weapons of mass destruction.[4] In reality, he had none and was increasingly cooperating with UN inspectors. However, President Bush argued against those claims, eventually giving Hussein an ultimatum: Leave the country or face an invasion. Despite fervent international protests, the United States and the rest of the coalition forces began hostilities when the deadline came and went. Although the conventional warfare was quickly over, as the Iraqis were no match for their foes, insurgents continued to be a thorn in the side of an increasingly isolated American presence for many years afterward. Though the eventual outcome of the US intervention has yet to be determined, deeming the action a success is seemingly impossible, given the nearly 200,000 civilian deaths that resulted from the conflict.

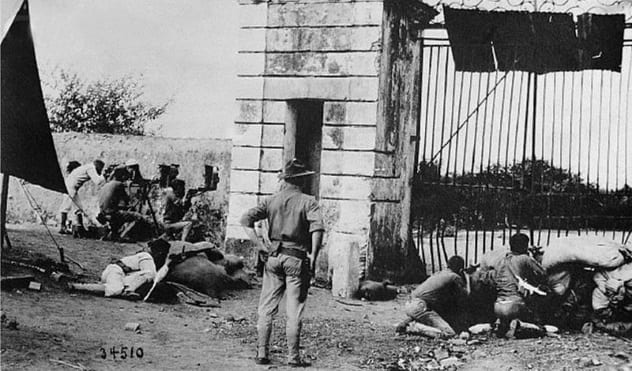

6 The First Caco War

By 1915, after four years of constant political turmoil, the US government saw the island nation of Haiti as a problem which could only be solved by force. Vilbrun Guillaume Sam, a ruthless dictator best known for his political executions, was ousted that year by the same forces which had been behind the last six coups: Haitian peasant militias known as cacos. Faced with an increasingly smaller chance of recovering the debts owed to them, France, England, Germany, and the US sent troops to the area.[5] However, it was the American forces who landed first, initially meeting with little resistance. A populist notion had helped instigate the latest coup, and the cacos were reluctant to give up as they had in the past. A brief guerilla war, the First Caco War, began and lasted for a few months, until US Marines stormed Fort Riviere, the final stronghold of the cacos. A pro-America politician named Philippe Sudre Dartiguenave assumed control of the country and remained in power until 1922. US forces remained in Haiti until 1934, when President Roosevelt transferred authority to the Garde d’Haiti.

5 Operation Just Cause

In 1989, Manuel Noriega, the infamous dictator of Panama, had been ruling for about six years, trafficking cocaine and helping the CIA with their various covert military operations throughout Latin America. By 1986, he had outlived his usefulness, and there were reports that he was a double agent. A US court convicted him on drug charges a few years later.[6] (Much of his involvement with the CIA came out as a result of various scandals, including the Iran-Contra Affair.) The 1989 elections resulted in a win by Guillermo Endara, the head of the anti-Noriega Democratic Alliance of Civic Opposition. Angered by the fact that his handpicked winner was defeated, Noriega declared the elections void, asserting himself as the de facto ruler of the country. Public pressure mounted on the US government in the form of various claims of softness on drug crime and the apparent escalation of threats against Americans living in the country. So, on December 20, US troops landed in a number of different spots with the intent of taking several strategically important sites. Noriega was eventually captured at the Vatican mission in Panama City, after he surrendered due to a combination diplomatic pressure from the Vatican and constant rock music (which Noriega hated). Endara was later sworn into office.

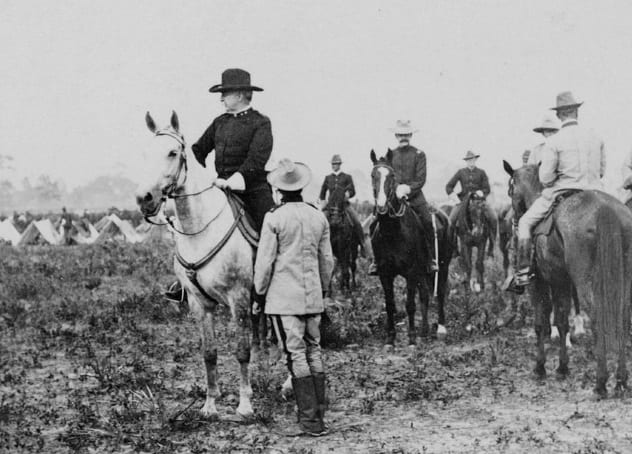

4 The Huerta Toppling

The year was 1913. Three years of bloody conflict had resulted in a number of overthrown Mexican presidents, and after a particularly violent series of days known as the Ten Tragic Days, General Victoriano Huerta was installed as president. However, the US, under President Wilson, was initially reluctant to recognize the newly minted dictator, instead hoping for democratic elections.[7] A year later, nine American sailors were arrested for allegedly entering a prohibited area in Mexican territory, setting off what would be known as the Tampico Affair. They were then paraded around the city, enraging the regional US naval commander. Ultimatums were issued, and when Mexico refused, President Wilson sent Marines to the port city of Veracruz. A relatively short battle ensued. The US forces took control of the city, only relinquishing it when Huerta resigned from office. Later, Huerta was contacted by German intelligence, who planned to use him to get the US bogged down in a war with Mexico. As he was heading back to Mexico from his then-home of New York, he was captured by US forces, who promptly charged him with sedition. He later died while in custody.

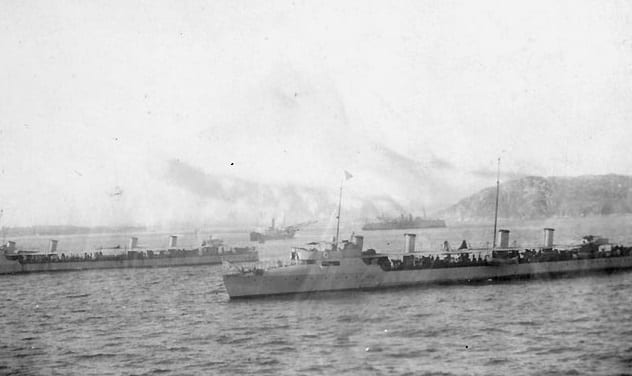

3 The Puerto Rican Campaign

During the Spanish-American War, a number of Spanish holdings in the Western Hemisphere were the site of conflict between the two countries, including the small Caribbean island of Puerto Rico. Less than a month after the onset of the war, US naval forces attacked San Juan, establishing a blockade. Eventually, land forces were deployed, and after only seven deaths, the US secured the island.[8] The war ended soon after, and Spain ceded a number of territories, including Cuba, the Philippines, Guam, and Puerto Rico. Though US control of Cuba was temporary from the onset, the other three territories were initially going to be permanent. Almost immediately, Puerto Rico came under the “leadership” of various military officers, who set about to Americanize the population, mostly through the use of schools and mandatory lessons in English. It would be another 54 years until the citizens of Puerto Rico were allowed to democratically elect their own leader, though they remain a territory of the United States.

2 The TPAJAX Project

In the early 1950s, Mohammad Mossaddegh was the democratically elected prime minister of Iran, and in an effort to gain more national control over their oil fields, he began to audit the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC), a British business. American fears were, as with many other similar examples, that the country would fall under the sway of the Soviet Union. Desperate to keep Communism from taking hold in Iran, the CIA began planning to overthrow Mossaddegh, hoping to reaffirm Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi’s power as monarch and install General Fazlollah Zahedi as the new leader of the country.[9] A joint task force of British and American intelligence began funneling money to various groups within Iran, who undertook terror plots designed to undermine public confidence in Mossaddegh’s government. (The AIOC itself contributed money for bribing officials as well.) A 1953 coup was successful, with as many as 300 people dying during the conflict and many more imprisoned or killed as a result of the shah’s military court tribunals. Pahlavi reigned for another 26 years, before anti-American sentiment, fueled in no small part by constant US involvement in Middle Eastern politics, resulted in the Iranian Revolution in 1979.

1 The Deposing Of Queen Liliuokalani

The first, last, and only reigning Hawaiian queen, Liliuokalani assumed the throne in 1891, after her brother’s death. Faced with declining royal authority, she sought to reaffirm the monarchy’s role in Hawaiian politics. In addition, she sought to lower the influence of foreign-born businessmen and landowners, many of whom were American. When they got wind of her plans, the wealthy elite conspired with the US military to depose her, and she was arrested in 1893. Led by Sanford Dole (yes, of the Dole Food Company), the Missionary Party assumed control of the country, establishing a provincial government with the stated goal of getting the islands annexed by the US.[10] Though the efforts were initially resisted by President Cleveland, who even unsuccessfully ordered Liliuokalani restored to the throne, Hawaii was eventually annexed in 1898. Liliuokalani went on to compose “Aloha Oe,” a song beloved ever since.