They were divided at the 38th parallel, but reunified in Sydney. It was probably only symbolic-perhaps even delusional, but when an event can bring two countries which are officially at war to march under the same flag, it gives the spectator an idea of the strength of the Olympic movement. A flag with the map of undivided Korea in blue over a white background was carried by Park Jung Chon, a North Korean judo coach and Chun Un Soon, a basketball player from South Korea while the band aptly played an emotional folk song. Same uniform, same flag, same song – it seemed for one fleeting moment in history, the two nations forgot the past and embraced the future.

The two were as different as they come. One, a white South African. The other, an Ethiopian. Derartu Tulu and Elena Meyer had just finished first and second in the 10,000 meters. What followed was perhaps the most poignant victory lap in history. Hand in hand, the two Africans celebrated their victory together. For many, it heralded South Africa’s re-entrance into the sporting arena after years of apartheid but it was the beauty of two African athletes, in their hour of glory to recognize each others performance that seemed to provide the shining light for the dark continent.

Pyambu Tuul represented Mongolia in the marathon at Barcelona in 1992. He came in last. When asked why he was so slow, he replied ‘”No, my time was not slow, after all you could call my run a Mongolian Olympic marathon record.” Not satisfied, another reporter asked him whether it was the greatest day of his life. To which came the reply which can throw anybody off their seats. “And as for it being the greatest day of my life, no it isn’t”, he said,””Up till six months ago I had no sight at all. I was a totally blind person. When I trained it was only with the aid of friends who ran with me. But a group of doctors came to my country last year to do humanitarian medical work. One doctor took a look at my eyes and asked me questions. I told him I had been unable to see since childhood. He said ‘But I can fix your sight with a simple operation’. So he did the operation on me and after 20 years I could see again. So today wasn’t the greatest day of my life. The best day was when I got my sight back and I saw my wife and two daughters for the first time. And they are beautiful.” Simple, ain’t it? It’s the races that we run within ourselves that are most important.

It seemed to be happening all over again. A sense of deja vu had set in. Dan Jansen, the speed skater who had promised so much, but had failed to deliver was competing in the 1000 meters finals at Lillehammer. Surely, it was his last chance at redemption. Four years earlier at the Calgary games, he had competed in the 500 meters speed skating event hours after hearing the news of his sister Jane’s death. He had failed to make much of an impact. The jinx continued in Albertville. Call it what you will-destiny, an act of divine providence, whatever-he skated like never before, created a world record, and took home the gold. And if there is anything called poignancy in sport-it is this- Dan Jansen, holding his little girl and looking up to the heavens saying ‘This is for you, Jane.’

Lake Placid, New York, 1980. The Soviets had invaded Afghanistan. Carter was not sending an American Contingent to the Moscow Summer Olympics. It was in this cauldron of spite that the American team comprising of mostly amateurs had just taken the lead against the mighty Soviets. Ten minutes of intense hockey followed, but the Soviets could not breach the American defense. With the clock winding down, ABC’s Al Michael’s immortal words ‘Eleven seconds, you’ve got ten seconds, the countdown’s going on right now! Morrow, up to Silk. Five seconds left in the game. Do you believe in miracles? YES’, were accompanied by jubilation on the rink as well as the stands. Decades later, its still the video you show your kids to teach them what it is to be American.

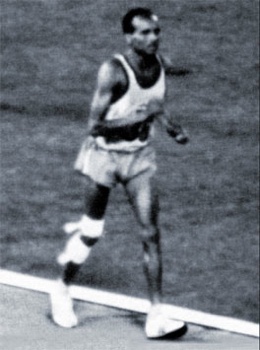

Momo Walde won the marathon gold in the high altitude of Mexico city in 1968. One hour later, a little known Tanzanian runner, John Stephen Akhwari entered the Olympic stadium – the last man to do so. Wounded after a fall and carrying a dislocated knee, he hobbled up to the track for for one last surge to the finish. He then retired to a thunderous applause by a small crowd which was lucky enough to get a glimpse of this gallant champion. It was later written of his perseverance – ‘Today we have witnessed a young African runner who symbolizes the finest in the human spirit. A performance that gives true dignity to sport – a performance which lifts sports out of the category of grown men playing in games.’ But Akhwari was far more modest. When asked why he did not quit, he replied,’My country did not send me 5000 miles to start the race. They sent me 5000 miles to finish the race.’

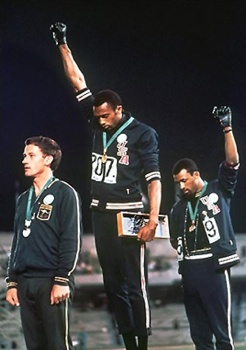

An image which even if you saw a thousand times, spoke to your heart in so profound a manner that it embodied the spirit of the times. The image is that of Tommie Smith and John Carlos raising a hand covered in a black glove with Peter Norman donning the Olympic Project for Human Rights badge. It will be remembered as the most iconic image of protest at the Olympic games, but all three of them were ostracized after. It was only years later that their act was to be recognized as a demonstration for dignity. It’s one of those moments when sport ceases to be just sport- it assumes the task of being a vehicle of change and progress.

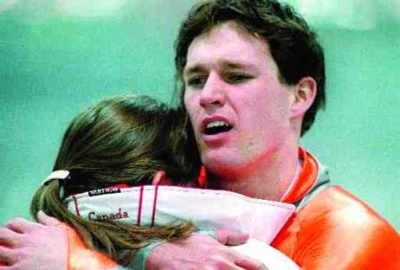

A career plagued by injuries, Derek Redmond arrived at Barcelona with an eye on the gold medal. It wasn’t to be. With 175 meters to go in his 400 meters semifinal he pulled his hamstring. The dream had ended it seemed. Not for Redmond though. The succeeding events are etched in the minds of millions. Crying he stands up again, only to try to finish on one leg. His father watching from the sidelines joins him with words of comfort – “We’ll finish together”.’ Strength is measured in pounds. Speed is measured in seconds. Courage? You cant measure courage’, were the words used by the IOC to promote the Olympic movement by the act of perseverance. But for Derek Redmond, it was the only plausible thing to do.

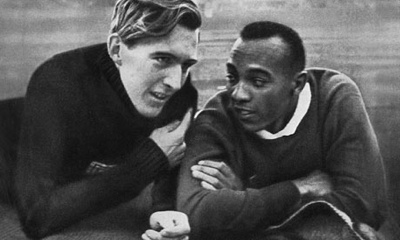

In full view of the Fuhrer, a nineteen year old German athlete gave Jesse Owens some advice – ‘play it safe, make your mark several inches before the takeoff board and jump from there.’ Owens, the grandson of a slave and the son of a sharecropper took the advice, qualified for the finals and took his tally of gold medals to four. The first to congratulate him was Luz Long. “It took a lot of courage for him to befriend me in front of Hitler… You can melt down all the medals and cups I have and they wouldn’t be a plating on the twenty-four carat friendship that I felt for Luz Long at that moment,” he said, recounting his rendezvous with the blue eyed German but for all his heroics, Jesse had to take the freight elevator in the Waldorf Astoria to attend his own reception.

At last he emerged from the background. A body weathered by Parkinson’s but the mind astute as ever. Shivering he lit the flame. No other sportsman in the history of sport had meant so much to so many as Muhammad Ali. For the dignity of the man was consummate – never relinquishing ideals for money or fame, Ali was the people’s champion – the underdog in sport and life. “They didn’t tell me who would light the flame, but when I saw it was you, I cried” said Bill Clinton. He wasn’t the only one.