Inspired by the works of acclaimed artists, horror movie directors have added audio, visual, and dramatic effects to their own creative visions, enhancing their artistic works with those of masters of expressionism, magic realism, realism, surrealism, modernism, romanticism, and the Baroque. The results are striking, adding richness and depth to the films’ own images and themes of the horrific and the terrible.

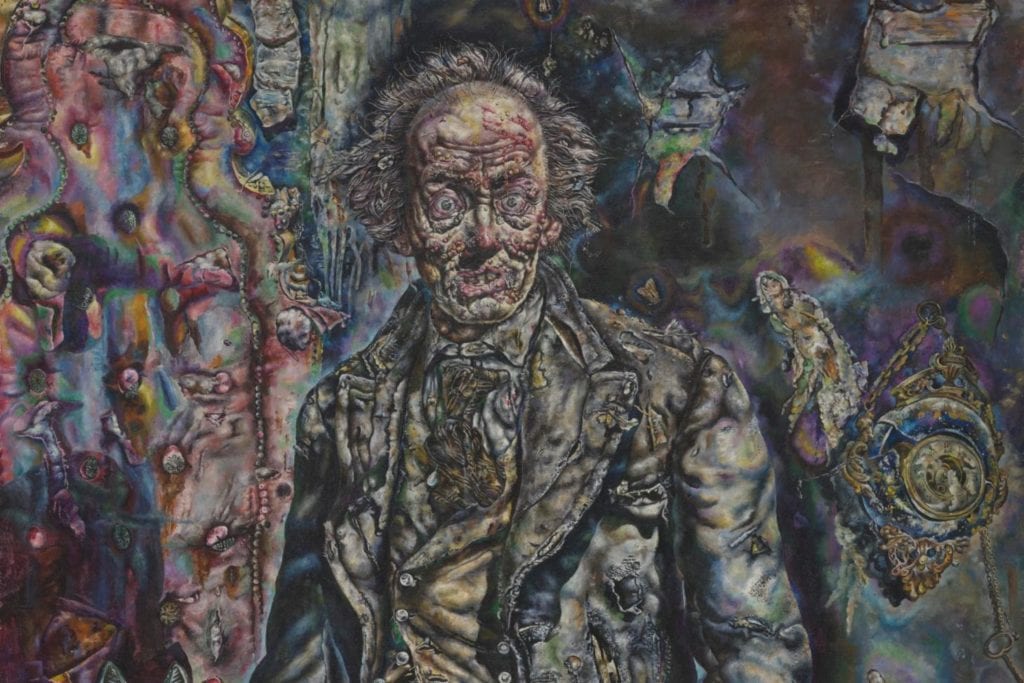

10 Picture of Dorian Gray

Although he may not be as famous as some of the other painters on this list, Ivan Albright, the acclaimed “master of the macabre,” was director Albert Lewin’s choice as the artist who would paint the portrait of the protagonist of his horror film The Picture of Dorian Gray (1945), an adaptation of Oscar Wilde’s 1891 novel. In the film, as in the novel, Gray, a handsome young man, commissions his portrait. As the result of a deal with the devil, the effects of Gray’s “dissolute and evil life” make their marks on the painting, rather than on Gray’s own appearance, and the vain reprobate remains as young and handsome as ever, despite the passage of time and his multitude of vile deeds. Although the movie was filmed in black and white, Lewin shot the portrait in full color to highlight Gray’s horrific transformation. In Albright’s oil painting, Portrait of Dorian Gray (1943-1944), Gray is aged, his brow wrinkled, his decayed flesh gray, his nose bulbous, his mouth twisted, and his face and hands smeared with blood. He looks quite mad, with staring, bulging eyes, and his filthy, tattered clothing, also smeared with blood, appears moldy. The furniture in the room in which he stands is likewise ruined, and plaster is missing from the walls. Bizarre faces and monstrous shapes seem to leer from walls, furniture, Gray’s clothing, and the floral carpet under his worn, blood-flecked shoes. Thanks to Albright’s “portrait,” it is clear to the audience that the state of Gray’s soul is, indeed, hideous, however youthful and handsome his fleshly form and countenance may appear; the painting is a perfect expression of the movie’s theme: evil corrupts the soul.

9 Witches Sabbath

In filming The Witch: A New England Folktale (2015), director Robert Eggers, who also wrote the movie’s script, strove to re-create the world of the seventeenth century, in which his drama takes place, so that the setting’s realistic depiction would add credibility to the film’s premise that witches really existed. To this end, he also sought to depict his own witch as believable. Although witches were “a lot more primal and a lot scarier” than people today might imagine, Eggers said, the witch in his movie must also impress his audience as someone whose existence would have actually been believed by her contemporaries. For this reason, she couldn’t resemble “fairy tale” versions of witches. One way he ensured the accuracy of his depictions of the time of his movie’s setting was to consult “historians and museums and living history experts.” Eggers also turned to a masterpiece by a famous painter for inspiration concerning how to depict his witch: Francisco Goya’s 1798 Witches Sabbath. Although the work is “outside” the time frame of Eggers’s seventeenth-century world, it is a timeless depiction of the subject, the director said, and the “best visual representations of witches you could ask for.” The painting shows the devil, in the guise of a goat, seated upright, its horns encircled by a garland, surrounded by witches, one of whom offers the central figure a nude newborn baby, while another presents a naked, emaciated child. Some of the witches are older than others, but none are young. Besides the presentation of the children, presumably as sacrifices, one of the more disturbing images in the painting appears in the background: three naked children’s bodies hung by their necks from a bare, sharpened branch stuck into the ground. Ironically, although Eggers uses Goya’s painting as a study of witches, seeing in their depiction a realistic presentation of how they might appear, Witches Sabbath, like the other paintings in the six works Goya devoted to “the theme of witchcraft,” are viewed by critics as “a satirical criticism of the superstitions of the educated society to which . . . the painter belonged.”

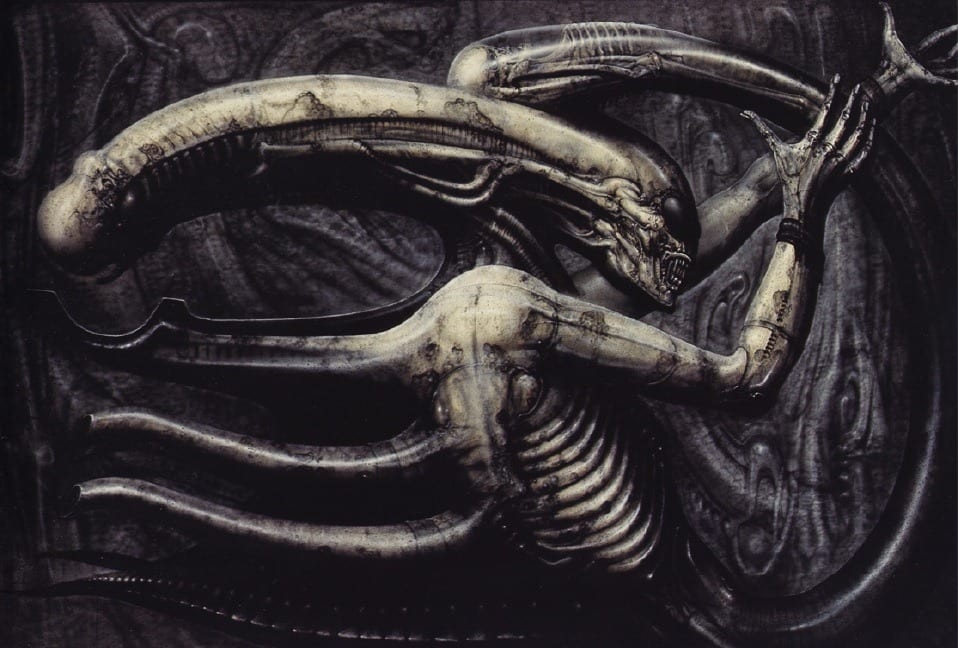

8 Necronomicon IV and Necronomicon V

The airbrushed paintings of surrealist H. R. Giger are disturbing, unforgettable, one-of-a-kind works featuring half-human, half-machine biomechanical figures; anthropomorphic shrubbery; eel-like monsters; fetuses; phallic shapes; machinery; and a bizarre, monstrous being that inspired the extraterrestrial creature in Ridley Scott’s 1979 science-fiction horror movie Alien. Painting and sculpting the creature on the set, as well as sculpting the interiors of the spaceship, Giger gave Scott what he wanted. Although the artist had preferred to design the alien creature anew, Scott, impressed by “the unique manner in which” Giger’s Necronomicon IV (1976) and Necronomicon V (1976) paintings “conveyed both horror and beauty,” demanded that Giger “follow their form.” As a result, not only was Scott’s audience terrified by Giger’s alien, but the artist won a 1980 Academy Award for Best Visual Effects for his work on the movie.

7 The Garden of Earthly Delights

Regan MacNeil, possessed by evil spirits, spouts, in addition to green projectile vomit, profanity, obscenity, blasphemy, insults, and invective at the two priests who have come to her home to exorcise the demons within. The teen’s bizarre behavior presented a problem. What does the voice of the devil sound like? The Exorcist’s director William Friedkin and Chris Newman, who worked in the film’s sound department, found their answer in an unlikely source: Hieronymus Bosch’s famous surrealist triptych, The Garden of Earthly Delights (1490-1510). Because Linda Blair, who portrayed Regan, was a child actor, the husky-voiced Mercedes McCambridge delivered much of the 1971 film’s foul language. Friedkin showed Newman Bosch’s painting, pointing out the dozens of demons in the panel of the triptych that represents the painter’s vision of hell. “That’s what the voice of Satan should sound like,” Friedkin suggested. To create the “elaborate . . . cacophony of sounds suggested by Bosch’s images of the demonic, “hundreds of . . . recordings” were used to create a mix of “diverse sounds” which included, among others, those of “croaking tree frogs and bumblebees.”

6 The Empire of Light

Rene Magritte’s surreal series of oil and gouache paintings, collectively called The Empire of Light (1940s-1960s), provided the inspiration for an exterior shot in Friedkin’s film. The paintings present a similar scene: a house, surrounded by nighttime shapes of trees, shrubbery, and shadows, illuminated only by a lamppost on the lawn and a light in an upstairs window, stands under a cloudy, blue daytime sky. Because the painting juxtaposes day and night in an impossible manner, many regard the scene it depicts as eerie—a perfect image for a film about a girl’s deliverance from demonic possession. Magritte’s painting inspired the scene in Friedkin’s film that shows the arrival of Father Merrin, as he stands alone on the street, beneath a lamppost, outside the house in which the devil awaits him. The bright sky represents heaven, the dwelling place of God, perhaps, while the darkness of the earth, the devil’s domain, symbolizes evil.

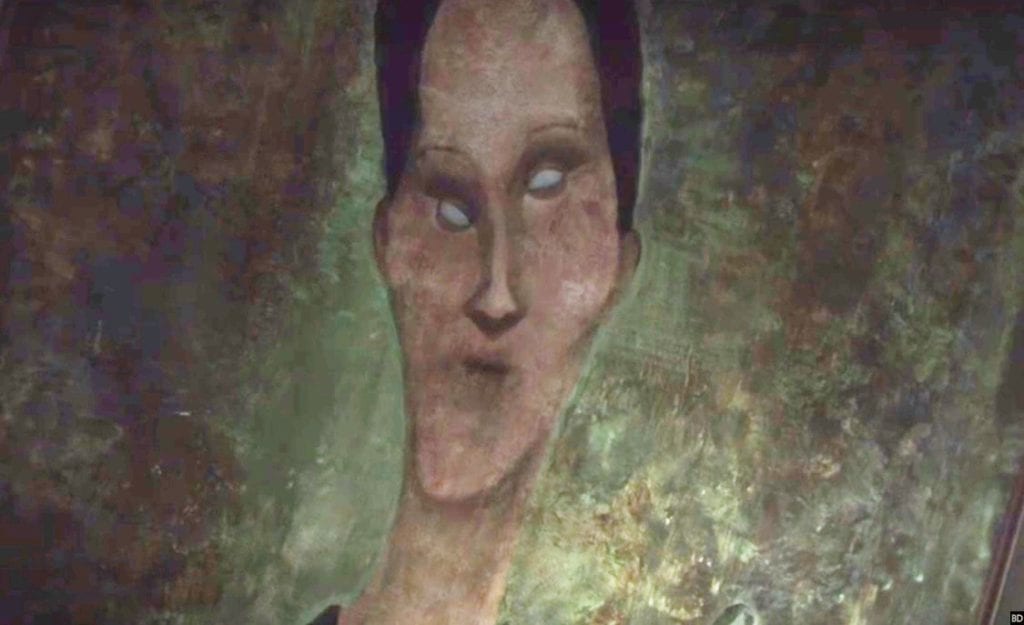

5 Amedeo Modigliani Paintings

The monster in Stephen King’s It is a shape-shifter, able to assume the form of anyone’s worst nightmare. Often, It appears as Pennywise, the mad, menacing clown, but, in director Andy Muschietti’s 2017 movie adaptation of King’s novel, It also transforms itself into such guises as a werewolf, a leper, and a female flutist who emerges from an Amedeo Modigliani painting in the office of the father of young Stanley Uris. The flutist is terrifying because her face is incredibly elongated, the features are beyond asymmetrical, because impossibly out of alignment, and the misshapen skulls seem to waver upon elongated necks. This particular avatar of It, the director explained, is “a literal translation of a very personal childhood fear. In my house, there was a print of a Modigliani painting that I found terrifying. And the thought of meeting an incarnation of the woman in it would drive me crazy.” The painting’s depiction of a female figure was so “deformed,” the director added, that it struck him as monstrous. In a sense, the bizarre flutist in his version of It is how King’s monster appears to him; It has taken the form most terrifying to the director, a realization of Muschietti’s own worst childhood fear.

4 The Nightmare

In 1781, Henry Fuseli painted Der Nachtmahr (The Nightmare), in which an incubus, or male sex demon, perches upon the abdomen of a sleeping woman dressed in a nightgown, her arms and head dangling off the bed and the rest of her body in a sensuous attitude. A horse’s head (belonging to the night mare, or nightmare) emerges from the bedroom’s dense shadows. In 2015, the famous painting inspired the motif for the film of the same title, directed by Akiz, a pseudonym for Achim Bornhak: the movie’s main character, Tina sleeps with the hideous demonic creature next to her. Is she imagining its presence? Is she the only one who sees it? Real or imaginary, how does the entity relate to Tina, and what does it represent? It seems that Bornhak is purposefully ambiguous about the creature’s significance and, therefore, the theme of his movie. The fetus-like being could represent Tina’s incipient madness. It could symbolize her estrangement from her peers. It might suggest Tina’s fear of rejection. The movie’s allusions to Stanley Kubric’s 2001: A Space Odyssey and to his A Clockwork Orange; to the mystical English romantic poet William Blake; and, of course, to Fuseli’s painting seem to frustrate interpretation as much as they might offer clues to the movie’s meaning, which makes critics wonder, even more, what Bornhak’s intentions could be. Perhaps, the film’s meaning depends on the audience’s own interpretations.

3 House by the Railroad

Known to millions, Norman Bates’s Victorian house, standing alone, on the hill overlooking his isolated motel, is one of the most unforgettable parts of the setting for Alfred Hitchcock’s macabre 1960 masterpiece Psycho. Far fewer are apt to know that the inspiration for this house of horrors is the 1925 painting House by the Railroad, by the celebrated Edward Hopper. The Museum of Metropolitan Art in New York City describes the painting’s residence as “a grand Victorian home, its base and grounds obscured by the tracks of a railroad [which] create a visual barrier that seems to block access to the house, which is isolated in an empty landscape.” It is just this mood that Hitchcock’s house atop the hill creates. Rather than inviting, the house is forbidding. It exists not as part of a larger community, but is, instead, isolated and alone; it cuts off its resident from the larger world, allowing Bates to live in an imaginary reality of his own devise, a world, which proves to be one both of loneliness and of madness.

2 Susanna and the Elders

Other paintings besides that of Hopper also inspire one of the settings for Psycho, the parlor behind Bates’s office in the motel. According to a trailer for the movie, Bates himself describes the parlor as his “favorite spot.” Pointing out one of the paintings on the parlor’s wall, he starts to explain its “great significance,” but fails to finish his thought. The painting is a print of William van Mieris’s 1731 Susanna and the Elders, which has more than a merely decorative or an aesthetic purpose; it covers the peephole through which Bates spies on Marion Crane. The painting itself recalls the thirteenth chapter of Daniel in the Catholic Bible (the book of Susanna in the Protestant apocrypha), in which Susanna, an upstanding young woman, is spied upon by elders as she bathes. When she refuses their demands to have sex with them, they then endanger both her reputation and her life by lying about their having caught her in the act of adultery. The presence of the painting therefore creates an allusion that underscores the parallels between Susanna’s plight and Crane’s own, intensifying the movie’s suspense. It also implicates the film’s audience, who, like the painting’s elders and Bates himself, also “spy” on Crane as she showers.

1 Venus with a Mirror

The parlor behind the office of the Bates Motel also displays Titian’s 1555 masterpiece Venus with a Mirror. Voluptuous, the half-naked goddess sits, her right arm and lower body draped in red velvet, gazing into a mirror held up for this purpose by a winged Cupid. A similar second attendant holds a hand mirror behind her head, so she can examine herself behind as well as to the front. Her rapt gaze suggests that she is pleased with what she sees. As Katrina Powers observes, in her discussion of the painting in The Journal of American Culture, “She holds her left hand up to her chest, perhaps to admire the gold bracelet and ring that adorn it,” as she also considers whether the jewelry is a good match for “her pearl earrings and the gold and pearl decorations she wears in her blonde hair.” In no way should her raised arm be interpreted as “shielding her nudity,” Powers declares, for it is rather, more likely, “one of [the] many poses” she strikes while contemplating “her own loveliness.” In the display of the Venus portrait alongside that of the Susanna painting, critics have seen multiple meanings, including “the connection between voyeurism, desire, and violence” (Donald Spoto); “voyeurism, wrongful accusation, corrupted innocence, power misused, secrets, lust and death” (Erik Lunde and Douglas Noverr); and “a rape fantasy” (Michael Walker). It may be, too, that, for Bates, Marion represents the temptation of female sexuality that his “mother” forbids him (Venus) and the desire to surrender to this temptation, through voyeurism (Susanna) that ends in violence and death for Marion, the embodiment of these conflicting impulses and needs.