The root of the English word cheese comes from the Latin caseus, which also gives us the word casein, the milk protein that is the basis of cheese. In Old English, caseus was c?ese or c?se, which became chese in Middle English, finally becoming cheese in Modern English. Caseus is also the root word for cheese in other languages, including queso in Spanish, kaas in Dutch, käse in German, and queijo in Portuguese. Caseus Formatus, or molded (formed) cheese, brought us formaticum, the term the Romans employed for the hard cheese used as supplies for the legionaries. From this root comes the French fromage and the Italian formaggio.

Cheese consumption predates recorded history, with scholars believing it began as early as 8000 BC, when sheep were first domesticated, to as late as 3000 BC. It is believed to have been discovered in the Middle East or by nomadic Turkic tribes in Central Asia, where foodstuffs were commonly stored in animal hides or organs for transport. Milk stored in animal stomachs would have separated into curds and whey by movement and the rennet and bacteria naturally present.

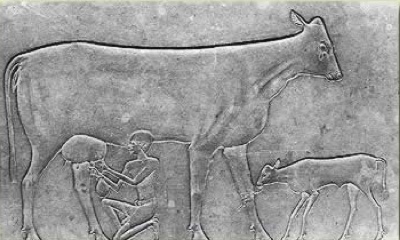

Egypt brings us the earliest archeological evidence of cheesemaking, found in tomb murals that date back to 2000 BC. These cheeses were likely to have been very sour and salty (lots of salt was needed to preserve the cheese in the hot, arid climate) and similar to a cottage cheese or feta in texture. Cheeses made in Europe didn’t require as much salt because of cooler conditions, thus paving the way for beneficial microbes and molds to form and give aged cheeses their interesting and robust flavors.

Ancient Greeks and Romans were the first to turn cheesemaking into a fine art. Larger Roman houses even had a special kitchen, called a careale, just for making cheese. After developing new techniques for smoking and adding other flavors into cheeses, the Romans spread this knowledge slowly through their empire. Local resources allowed for different varieties to develop along the way.

After the fall of the Roman Empire, innovative monks were responsible for inventing some of the classic varieties of cheese we know today. According to the British Cheese Board, Britain has approximately 700 distinct local cheeses. It is thought that France and Italy have perhaps 400 each. The varying flavors, colors, and textures of cheese come from many factors, including the type of milk used, the type of bacteria or acids used to separate the milk, the length of aging, and the addition of other flavorings or mold.

Although most cheese is produced from cow, sheep, or goat’s milk, it can and has been made from a plethora of milk-producing animals. A farm in Bjurholm, Sweden actually makes moose cheese. The lactation period of moose is short, lasting from about June to August, and the farm, owned by Christer and Ulla Johansson, keeps three moose that produce only 300 kilograms of cheese per year. The moose cheese sells for roughly US$1000 per kilogram. Places in Russia also produce moose milk but have not had success with moose cheesemaking due to its high protein content.

The United States is the top producer of cheese in the world, with Wisconsin and California leading the states in production. Although the US produces the most cheese, Greece and France lead the pack in cheese consumption per capita, averaging 27.3 and 24.0 kilograms per person in 2003 respectively. In the same year, the average US citizen consumed around 14.1 kg, although cheese consumption in the US has tripled since 1970 and is continuing to increase. Pictured above is cheez whiz. Keep it classy.

Limburger cheese is notorious for its strong and generally unpleasant odor. The bacteria known as brevibacterium linens causes this. It is also found on human skin and is partially responsible for body odor. The Chalet Cheese Cooperative, located in Monroe, Wisconsin, is the only maker of limburger cheese in North America today.

When eating cheese fondue, make sure to save room for “the nun” at the bottom of the pot, or la religieuse. Religieuse means nun in French and usually refers to a type of pastry. There is much speculation as to why the cracker-like, toasted cheese layer found in the bottom of a caquelon is called la religieuse, ranging from the legend that monks saved the last remaining bits of fondue for the nuns to the idea that eating it is a religious experience. In German, it is called the Großmutter or grossmutter, which translates to grandmother. The meaning behind this use is also unclear.

“A cheese may disappoint. It may be dull, it may be naive, it may be over sophisticated. Yet it remains, cheese, milk’s leap toward immortality.” Clifton Fadiman (American writer and editor; New Yorker book reviewer, 1904-1999) “A dinner which ends without cheese is like a beautiful woman with only one eye.” Jean-Anthelme Brillat-Savarin (French lawyer and politician, epicure and gastronome, 1755-1826) “Many’s the long night I’ve dreamed of cheese — toasted, mostly.” Robert Louis Stevenson (Scottish novelist, poet, essayist and travel writer, 1850-1894) “How can you govern a country which has 246 varieties of cheese?” Charles De Gaulle (French general and president, 1890-1970)