As curious as gruesome finds are, ancient teeth are not just about the gore. In recent times, they rewrote Egyptian jobs, proved that dinosaurs migrated, and finally gave scientists a bead on what our mysterious relatives, the extinct Denisovans, looked like.

10 The Subway Teeth

In 2018, an excavation found teeth in Australia. It was not a dozen molars unearthed in a cave somewhere. All sorts littered a Melbourne subway, numbering over 1,000. Thankfully, it was not a crime scene. The teeth had been discarded by several 20th-century dentists, including J.J. Forster who had an office at 11 Swanston Street. He pulled teeth from 1898 to the 1930s, a time when cocaine was used to make patients happy before an extraction. There were also dentures and a tooth patched with a gold filling. Many showed the true reason for visiting the practice—enormous cavities. The holes must have been agonizing, but that was just the start. Despite Forster’s 1924 newspaper ad that promised to “[remove] teeth truthfully without pain,” dentists of the time approached a doomed tooth with forceps.[1] How did the teeth end up in the subway? Their location was a good clue. Found inside an iron pipe and the surrounding soil, the dentists probably flushed the teeth down a drain to get rid of them.

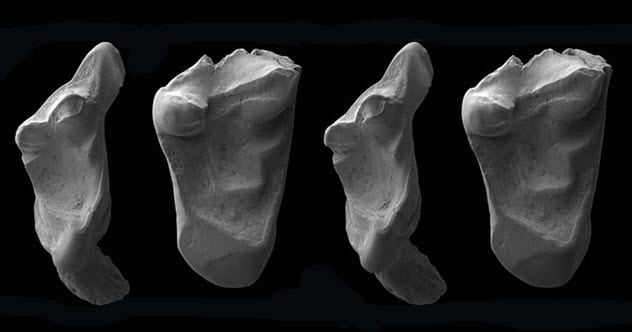

9 The Megalodon Evolution Mystery

A 2019 study examined an ancient predator that never fails to capture the imagination. Megalodon was the largest shark in existence, and its teeth were serrated nightmares. The researchers were curious about how megalodon’s psychotic teeth became so perfect for the job. They turned to 359 fossil teeth. The collection hailed from Chesapeake Bay in Maryland where the land was once a prehistoric ocean. The study found that megalodon’s teeth were a slow acquisition. Remarkably, evolution designed it over millions of years. The process went something like this. Otodus obliquus, the oldest ancestor of megalodon, terrorized the sea between 60 and 40 million years ago. Their jaws had “cusplets,” tiny teeth on both sides of larger teeth. It was basically a three-pronged affair that gripped and mutilated prey.[2] Some of the Maryland teeth belonged to Carcharocles chubutensis, an immediate ancestor. Comparing their teeth to megalodon’s showed that the cusplets took millions of years to disappear while serrations evolved on the main tooth. Scientists still cannot explain why the process took so long or why the cusplet feature vanished.

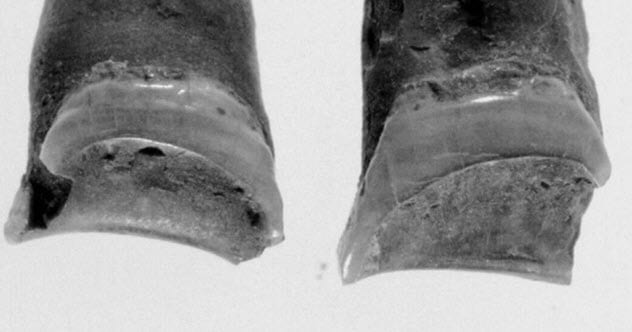

8 Oldest Right-handedness

Around 1.8 million years ago, a hominid damaged its front teeth. The individual belonged to the species Homo habilis, a member of the human family tree. Its fossilized remains turned up in Tanzania in 1995. A later study from 2016 found that the dental damage championed an unusual trend—right-handedness. The scientists who examined the grooves felt that they were caused by feeding habits. More precisely, the primate used its teeth to anchor food while gripping it in one hand and sawing away at it with a stone tool in the other. A few times, the tool overreached and scratched the enamel. The orientation of the marks suggested that the hand using the tool—thus the creature’s dominant hand—was the right one. This is the oldest such evidence in the archaeological record and the first of many fossils that might prove that right-handedness has always been more prevalent. The researchers are tentatively hoping for more. Since genetics and certain brain regions determine “lefties” and “righties,” understanding more about the history of human hands and brains can perhaps solve why there are fewer left-handed people in the world.[3]

7 A Mosasaur Scuffle

Miners found an ancient predator in 2012. Discovered in Alberta, Canada, the creature was a mosasaur. These reptiles resembled dolphins and lived in the ocean. The specimen reached an intimidating 6.5 meters (21 ft) in length. Scientists found a tooth stuck in the animal’s lower jaw that had come from another mosasaur. Around 75 million years ago, the two predators had a nasty encounter. The attacker came at an angle from below and bit its opponent’s face three times on the left side. One bite was so hard that a tooth got pulled and stayed behind in the wounded mosasaur’s jawbone.[4] Previous fossils showed that mosasaurs ate each other, but this lucky duck survived. It also represents the first nonfatal fight between mosasaurs in the fossil record. The wounds healed. However, another unidentified species bit the same mosasaur on the right side of the skull. The incomplete healing showed that it died shortly afterward.

6 Evidence For Dinosaur Migration

Theories suggested that some dinosaur species felt a seasonal urge to travel, but there was no evidence. In 2011, that changed. Scientists examined the teeth of sauropods, enormous herbivores that lost their snappers in Utah and Wyoming. Both states are low-altitude regions. But when the researchers analyzed the teeth for oxygen-18 isotopes, they found something interesting. The signature of the isotopes came from a high-altitude environment. During the sauropods’ lifetimes, western North America had wet and dry seasons. For an animal that was basically a giant, the dry period would not have provided enough food or water. It would appear that the creatures migrated over 560 kilometers (350 mi) to find sustenance in the highlands. While staying there, the isotopes settled in their enamel. The dinosaurs shed their teeth every five or six months, and in this case, the scientists were lucky to find the highlands’ isotopes in teeth lost at a low altitude. It gave the first direct evidence that certain dinosaurs migrated.[5]

5 Humanity’s Ratlike Ancestors

In 2017, an undergraduate combed Dorset for inspiration for his dissertation. Mainly searching for fossils, he found and took two teeth to the University of Portsmouth for identification. Researchers at the university recognized them straight away and were more than a little shocked. The teeth had come from mammals that lived 145 million years ago during the Cretaceous Period. The creatures belonged to two new species, Durlstotherium newmani and Durlstodon ensomi. Their group, Eutheria, became the most successful mammal family that led to all placental mammals. The newness of the two ratlike species was not the surprise. Instead, it was the age of the fossils. They resembled those of animals that lived 60 million years later. Despite being much older, the “rats” were not an underdeveloped prototype. The teeth showed that the mammals used their teeth like tools to cut and crush food. This was a highly advanced feature for the time.[6] The teeth also came from older adults, indicating how adept the species was at surviving. Interestingly, as the oldest undisputed Eutherians, they were also the earliest mammalian ancestors of humans ever found.

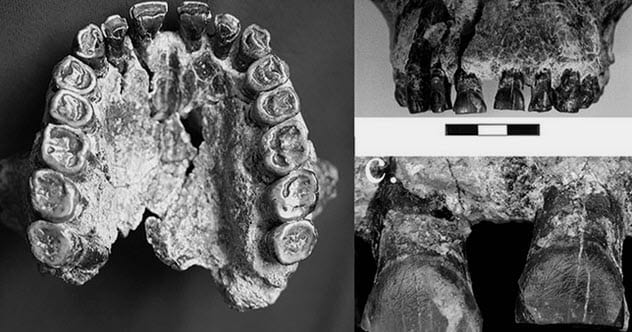

4 An Egyptian Craftswoman

The records of ancient Egypt are more detailed than most extinct cultures. As scholars studied texts, paintings, and other sources, they concluded that women had only seven professions. They included priestesses, dancers, singers, musicians, mourners, weavers, and midwives. A 2019 study reviewed the body of a woman who died 4,000 years ago and was buried at Mendes, a city that was once ancient Egypt’s capital. Her high-status grave was originally found in the 1970s. The woman was around 50 years old when she died, and her teeth held a surprise for researchers. On 16 of her teeth, there was damage unrelated to eating. Instead, it showed another profession open to Egyptian women. The lines were consistent with craftspeople, who used their teeth while working with plant material. The analysis convinced the researchers that she was a highly respected craftswoman who probably shaped papyrus into vessels, curtains, mats, and sandals. Only the outer rind of the stalk was used to produce the items. If she used her teeth to remove the bark, it explained the marks.[7]

3 The Eppelsheim Teeth

In 2016, two teeth turned up close to Eppelsheim. The German town was known for producing regional fossils, but this find was exceptional if only for the division it caused among experts. The molar and canine tooth were well-preserved, a remarkable feat when considering the claim of those who said they were 10 million years old. If confirmed, the age and location will change our view of human history. The canine tooth, in particular, resembles those of primitive human ancestors. Therein lies the controversy. Similar teeth had been found only in Africa, and those were millions of years younger. The accepted timeline of human history states that people evolved in Africa and migrated to Asia and Europe around 100,000 years ago. The ancient pair suggested that an unknown branch of humanity evolved in Europe independently of Africa. The archaeologists who found the teeth supported this theory and claimed that they were from the same individual. Experts in the other corner believe that the teeth came from two species belonging to a broader collection of primates instead of a mysterious human line.[8]

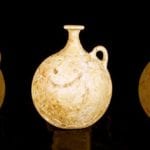

2 A Tooth-Studded Purse

Modern accessories glitter with everything from gems to sequins. During Germany’s Stone Age, however, high fashion was more enamel and less emerald. Dog teeth graced necklaces and hair ornaments for men and women. But one artifact topped them all. In 2012, an archaeological dig near Leipzig opened a grave and found what could be the world’s oldest purse. Although the original material or leather had decomposed, its gruesome decorations remained. Made between 2500 and 2200 BC, the designer added over 100 dog teeth from dozens of animals. The pieces were tightly packed in rows and all pointing the same way. The arrangement’s shape suggested that the dental bling once decorated the bag’s flap. Even for a time when canine accessories were common, the handbag was a rare find.[9] However, it was not the first object studded in this manner. Other Stone Age graves have produced patterns of wolf and dog teeth that once studded blankets, which have since fallen apart and disappeared.

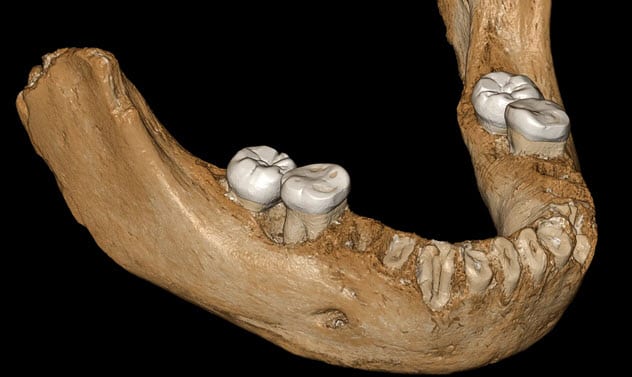

1 New Denisovan Information

The Denisovans represent another branch on the human tree. Their existence only came to light when bone fragments and teeth were found a few years ago inside a Siberian cave. Although DNA showed they were once widespread in Asia and Europe, the species remained mysterious. Discovering additional Denisovan remains became the grail for archaeologists, but few knew that a spectacular piece had already been found during the 1980s. A monk had entered a cave on the Tibetan plateau and saw a human jawbone. He passed it on to a living Buddha, who eventually gave it to the researchers. Their study was groundbreaking. Released in 2019, it gave valuable information about the Denisovans after the team extracted proteins from one of the 160,000-year-old molars. The results showed that Denisovans had a more primitive appearance than Neanderthals. This was backed up by the powerful jaw and unusually robust teeth. The most remarkable was the gene that allowed them to live at freezingly high altitudes without succumbing to hypoxia. This explains why certain Tibetan populations today inherited Denisovan genes and rarely suffer from low-oxygen conditions.[10] Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages