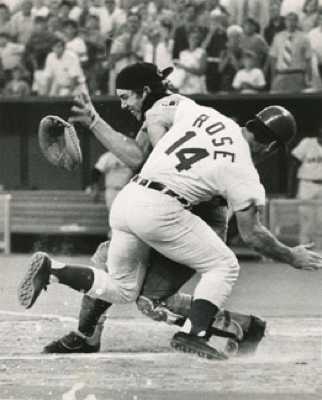

Caption: Pete Rose Collides with Ray Fosse One of baseball’s most famous collisions occurred at the very end of the 1970 All-Star Game, when, after the ball was hit, Pete Rose of the Reds, on third, charged as fast as he possibly could for home, but instead of sliding, he simply tackled Fosse at full speed. Both men weighed 200 lbs or more and Rose got the better of it, tagging the plate and sending Fosse sprawling. He hit him so hard he dislocated Fosse’s right shoulder, and some claim this caused Fosse’s career’s downfall. Rose was heavily criticized for what some called “too much aggression” given that winning the All-Star Game didn’t really matter. Rose did not apologize, and stated that he was just trying to win, lending credence to his nickname, “Charlie Hustle.” But if anyone should complain about this much aggression, they should first consider the next entry.

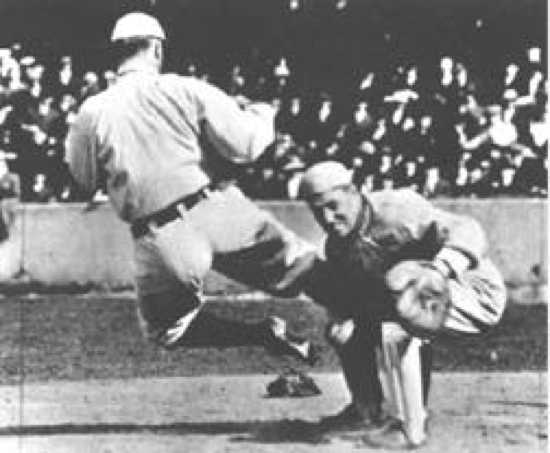

Caption: Cobb Steals Home This photograph corroborates all the biographical literature’s descriptions of Ty Cobb’s true nature on the field. He didn’t play to win. He fought to kill. This incident occurred on 4 July 1912, and shows Cobb “stealing home” not by sliding under or around the catcher’s mitt, but by deliberately dropkicking him right in the groin. Baseball shoes back then had cleats, but not dull, hard plastic. They sported iron spikes in the toes and heels, and with them Cobb could run 100 meters in 10 seconds flat, even wearing his baggy uniform. He stood on third base and took out a steel file, sharpened his spikes, and then charged right in to the catcher. This was not against the rules and Cobb was ruled perfectly safe while the catcher writhed on the ground. His aggression is a substantial reason why Cobb holds the record for all-time home base steals with 54. Max Carey, who played from 1910 to 1929, is second, with 33. The unfortunate catcher in the photograph is Paul Krichell.

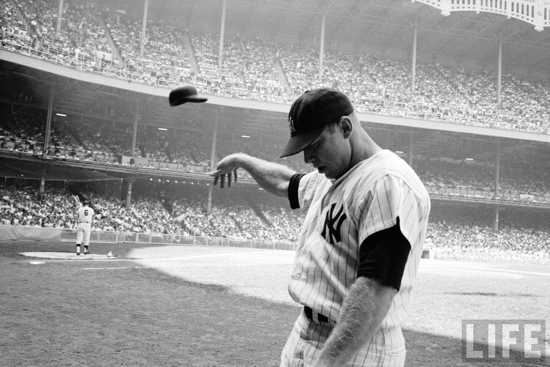

Caption: Mickey Mantle Tossing His Helmet Mantle was one of the most powerful batters ever, and one of the fastest base runners. He had terrible knee problems throughout his career, and was still able to sprint from home to first in 3.4 seconds. He retired with a lifetime batting average of .298, which is very good, and 536 home runs, which is phenomenal. Many of his home runs were titanically powerful blasts. One famously measured 565 feet from home plate. Some say that another would have traveled 634 feet had it not struck the upper deck facade of Yankee Stadium’s grandstand. To say that Mantle had his share of joyous moments, both for himself and for his fans, is an understatement, but like any great player, he couldn’t stand playing poorly. He felt he had to give the fans what they paid to see. This photograph was taken in 1965 and shows Mantle having just struck out. Up to bat after him is John Dominis in the background. The photograph is very artistic, and does a great job showing the tragedy of the game. It has its highs, but it must have its lows, and here, Mantle is throwing his helmet away in disgust. He did not score a hit in this game. The picture also shows a key to his legendary power: his gigantic forearms. They’re almost Popeye-huge. Thus, he was able to swing the bat with excellent wrist control to give it extra snap.

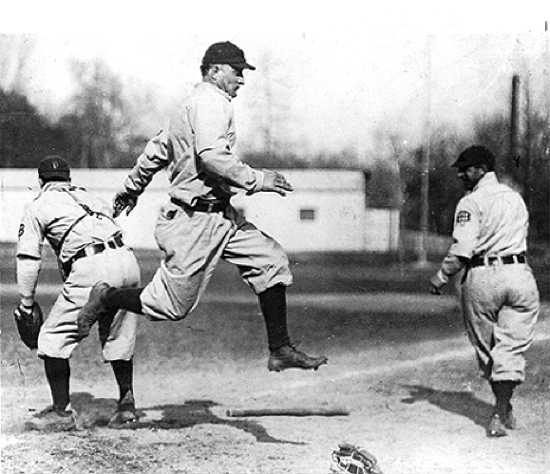

Caption: Honus Wagner in Mid-air Wagner’s nicknames were “the human vacuum cleaner,” and more well-known, “the Flying Dutchman.” He came from the Pennsylvania Dutch country, itself a misnomer, since it was originally Pennsylvania Deutsch. The inhabitants are largely descendants of German immigrants. Wagner’s full name was Johannes Peter Wagner. He was one of the absolute fastest base runners in the game’s history, and this photograph shows a little of that. He has just finished running from third to home and is making one final leap to tag the plate. His feet are both at least a foot off the ground and he makes it all look as effortless as “the man on the flying trapeze.” Wagner was an extremely nice guy to everyone, as opposed to his chief rival, Ty Cobb, and not nearly as well known as Cobb due to Cobb’s famed surliness. But Wagner was just as adept as stealing bases, tying with Cobb for the record of most single-inning steal cycles in history: on four separate occasions, he stole second, then third, then home in the same inning.

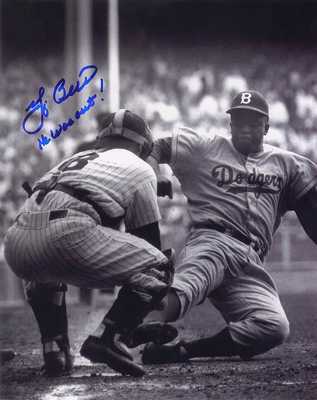

Caption: He Was Out! This photograph shows Jackie Robinson, the first black player allowed into the majors, stealing home against possibly the greatest catcher ever, Yogi Berra. This occurred in Game 1 of the 1955 World Series, which Robinson’s Dodgers won, their first ever. It is part of a series of photos showing Robinson running the whole baseline and Berra getting into position to stop him. The umpire ruled that Robinson’s foot slid under Berra’s mitt and tagged the plate before Berra could bring his mitt down. The photo was always somewhat well-known but became legendary when Berra was stopped on the sidewalk one day years later by a fan who had a copy of it. Berra smiled and signed it, “He was out! Yogi Berra,” and then explained that he grazed Robinson’s shoe with his mitt, but that the umpire was behind Berra and couldn’t see. From then on, copies of the photo became popular collectibles, and Berra has never disappointed, always signing them, “He was out!” He even signed one for President Lyndon Johnson.

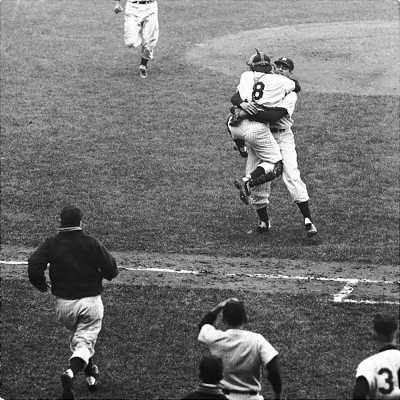

Caption: Yogi Berra Hugging Don Larsen Don Larsen is not generally thought of as one of the greatest pitchers in history, but anyone who pitches a perfect game deserves to be on such a list. His perfect game occurred as Game 5 of the 1956 World Series, the only perfect game in World Series history. The suspense, the thrill, the jubilation, thus, could not have been topped. A perfect game is the ultimate achievement for a pitcher (except perhaps striking out all 27 batters with 3 pitches each, which has never happened). There have only been 23 in history. There were some close calls in this game, especially Gil Hodges’s screaming line drive to left-centerfield. No less than Mickey Mantle sprinted, dove, and caught it in the air. The last batter Larsen faced was Dale Mitchell, who retired with a massive .311 average. Larsen managed a called third strike to end the game, 27 up, 27 down, no hits, no runs, no walks, no struck batters, no errors. Yogi Berra immediately leaped up, ran, and jumped into Larsen’s arms as the crowd erupted. One of the most purely joyous moments baseball has seen.

Caption: Lou Gehrig Looking at his Trophies Possibly the saddest moment in baseball was immortalized in multiple photographs, since every major newspaper sent someone to take them. By the time Gehrig called it quits, the fans knew something was terribly wrong, and once his strange new disease (and its method of killing someone) made the papers, everyone in the country seemed firmly supportive of Gehrig. During the farewell between games of a doubleheader on 4 July 1939, 61,808 fans, plus Babe Ruth, and the two teams, Yankees and Senators, paid Gehrig the tribute he deserved. He was presented with over two-dozen trophies from various people and organizations. The photograph shows him with his head bowed before them while both teams and others stand behind him, hats in hands, and Mayor Fiorello La Guardia speaks at the microphones. The reason all the trophies are on the ground is because Gehrig no longer had the strength to hold one up.

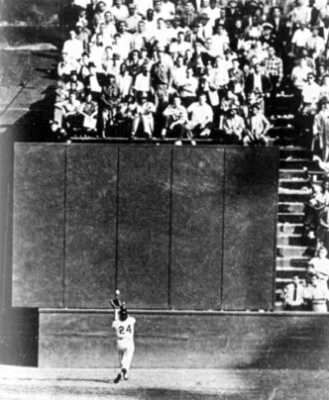

Caption: The Catch This famous play was immortalized by a still-frame of the televised coverage of Game 1 of the 1954 World Series between Willie Mays’ Giants and the Cleveland Indians. Victor Wertz slammed a 450 foot fly ball into dead centerfield of the Polo Grounds “that would have been a home run in any other stadium, including Yellowstone,” as one sportswriter said. Mays was playing shallow center and thus had a long sprint after the ball, watching it over his shoulder, and a sequence of photos shows the whole play. The final instant before the ball lands in his glove only three or four feet from the wall will never be forgotten. The ball is about one and a half feet out of his glove, and he makes a perfect basket catch, running at full speed. He then whirled and flung the ball back to third so hard his hat fell off, a typical performance.

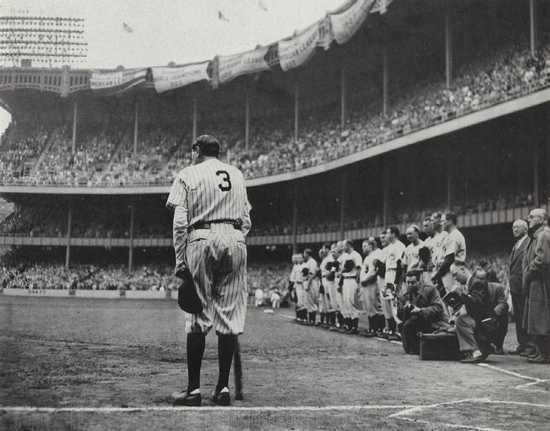

Caption: The Babe Bows Out All the famous shots of Ruth standing and looking almost straight up immediately following another titanic home run blast are what most of us remember about him. But the finest depiction of him shows him as just flesh and blood like anyone else, an old man about to be given a farewell by his old team and thousands of fans at Yankee Stadium, having completely used himself up in hard-partying style for the last 30 years. The photograph was taken by Nat Fein, who won the Pulitzer for it in 1949. He took it on 3 June 1948, only two months before Ruth’s death from nasopharyngeal cancer. Ruth was known as the most powerful batter anyone had ever seen, bar none. Today, he is still respected with awe by professional players. Some say he was simply a freak of nature to be able to play so well and party so hard without any detriment to his performance. He routinely slammed baseballs over 550 feet away, which is beyond belief. His longest shot was in 1926 against Ty Cobb’s Detroit Tigers. He knocked the ball out of Navin Field and onto the roof of a livery across the street, at least 625 feet away. He knocked balls completely out of every stadium in which he played, except Yankee Stadium. He did, however, regularly knock them out of the Polo Grounds, an astounding feat, before Yankee Stadium was built. The photograph shows a tired old man leaning on his bat, and you might not have known who he is were it not for the famous number 3 on his back. Everyone likes to think of him as immortal. But this photograph shows otherwise. He was just a man, which makes his feats even more impressive.

Caption: Cobb Steals Third The finest baseball photograph because it captures the fierceness and intensity of the game’s most daring, aggressive player. It was almost impossible to record motion pictures of ball games in Cobb’s day, and still photographs rarely caught the gritty speed and determination everyone lauded about Cobb. Charles Conlon snapped the photograph on 23 July 1910, using a large format Graflex camera on a tripod. He was on the field, behind third base in foul territory. Conlon was quite familiar with Cobb’s demonic abuse of the baselines and basemen and had his camera ready with Cobb on second. True to form, Cobb stole second, banking on the catcher’s weak arm, and knocking third baseman Jimmy Austin out of the way. He deliberately tripped Austin with his shoulder, forcing him to jump out of the way and thus miss the catcher’s throw. What the picture doesn’t show is that Cobb leaped up and stole home while the left fielder went for the ball.