Fleeing a plague and sitting it out in the countryside was one of the only things most people could do. Of course, they often spread the plague to the “safe” places to which they ran. So even this had only limited success. With everyone around them succumbing to mysterious illnesses, the people of the past had nothing to lose by trying what seem like ridiculous tactics to us. Here are 10 historic ways that people tried to beat plagues. Top 10 Worst Plagues In History

10 Smells

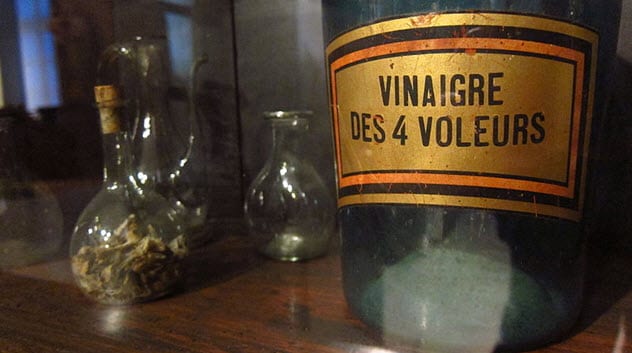

Miasma theory, which suggested that illness was caused by bad air and odors, placed a great deal of faith in the power of smells to prevent illness. It was believed that removing bad smells was one way to stop disease. In 1357, the city of London threatened people with fines if they left any offensively smelly animal products or dung in the streets. For those unable to make their environment less odoriferous, there was the option of using perfume and other sweet smells to mask the stench. However, one group of people is said to have invented a cure for the plague for less than wholesome reasons. Four Thieves Vinegar (aka Marseilles Vinegar) was a concoction of vinegar, herbs, spices, and garlic whose strong smell was thought to prevent the plague. The recipe for this mixture was supposed to have been created by a group of four thieves who wanted to break into houses where people had died of the plague without catching it themselves. When apprehended, the thieves surrendered their secret formula to avoid being hanged.[1]

9 Masks

Some individuals used smells to save themselves for more noble reasons than theft. Medieval doctors who dealt with plague victims were often shown wearing extraordinary beaked masks. Although they look absurd to us, they were the high-tech hazmat suits of the Middle Ages. Doctors in their plague gear wore waxed aprons to stop blood and other bodily fluids from soaking into their clothes. Leather gloves kept them from coming into contact with their patients directly. Polished slices of crystal in their masks allowed them to see clearly but kept droplets of infectious material from reaching their eyes. However, from the physician’s point of view, the most effective piece of kit was the beaked mask. Not knowing how diseases spread, they thought the putrid aromas of the sick actually caused illness. So, the beaked mask was stuffed with pungent herbs and spices to purify the air they breathed. Some doctors went further by holding garlic in their mouths while examining the dying.[2]

8 Fires

When personal protection was not enough, city authorities sought to drive out diseases by changing the air of the entire city. One of the best ways to do this was to light enormous bonfires whose heat and smoke was thought to clean the air. When the Great Plague of 1665 hit London, an order went out from the Lord Mayor that all inhabitants of the city were to “furnish themselves with sufficient quantities . . . of combustible matter to maintain and continue fire burning constantly for three whole days and nights.” The given reason was that this had worked in the past and in other countries. For three days, the streets were kept empty except for people tending fires and watching that sparks did not ignite nearby houses. The diarist Samuel Pepys saw fires burning throughout the whole city. Alas, they did not work in stopping people from dying by the thousands.[3] For a time, smoking was thought to be good for your health. After all, what could be healthier than carrying a tiny bonfire of tobacco around with you in your pipe?

7 Kill Cats

During the Great Plague, the city authorities of London also declared that there should be a culling of cats and dogs. Unfortunately, this plague was spread by rats and fleas. Without cats and dogs to keep the rat population down, it is sometimes thought that this measure helped to prolong the length of the plague. Cats have always had it hard in times of crisis. Until the 18th century, it was a common entertainment in France to gather cats in a net or cage and hoist them over a fire to watch them burn to death. The animals’ ashes were thought to be a powerful protection against witchcraft and the cause of good luck. There may have been some use in getting rid of cats, however. As they can carry fleas and spend a lot of time around humans, they may well have been carriers of the Black Death after all.[4]

6 Bloodletting

Bleeding patients has been a favorite pastime of doctors for millennia. The ancient doctor Galen, who shaped medical practice for centuries, was such a fan of bloodletting that his fellow doctors mocked him for it. Once, after Galen tried to bleed a fever out of a patient, there was so much blood on the floor that they said, “You really slaughtered that fever.” Later, doctors thought themselves much more sophisticated that Galen. Rather than simply cutting up patients and letting the blood pour out, they attached leeches to the body to suck out the blood. Leeches were collected by individuals (usually women) wading into the water where the critters lived. The leech finders had bare legs and simply waited for the bloodsuckers to attach themselves. These leeches were then sold for a high price. Leeches were a relatively painless and risk-free way of getting some of your blood out.[5] Today, if you feel your humors are out of balance, most modern doctors would suggest trying something other than bleeding. On the other hand, leeches have made a comeback in certain medical uses. 10 Weird Epidemics That Remain A Mystery

5 Quarantine

One of the fastest ways for diseases to spread in the Middle Ages was on ships. People were crammed together in close and unhealthy quarters. This made these vessels the perfect breeding grounds for diseases. Once sailors and passengers went ashore, a plague could soon spring up. This relationship between ships and disease was soon noticed, and the city of Venice took measures to stop it. Starting in 1448, when a ship reached the city, it was forced to wait at anchor for 40 days before the crew and goods could leave the vessel. This period of 40 days gives us the word “quarantine” today.[6] Forty is also a biblical number related to purity as when Jesus went into the desert for 40 days. Despite being a number plucked from the Bible, the Venetians seem to have struck it lucky. Modern medicine suggests that most people suffering from the bubonic plague go from infection to death in around 37 days.

4 Cordon Sanitaire

Sometimes, it was an entire empire that took action to keep plague out. In 1770, Empress Maria Theresa of Austria set up a cordon sanitaire between her lands and those of the Ottoman Empire. This sanitary cordon sought to keep the plague out of Austria—and it worked. The border lasted for 101 years. During that time, there were no outbreaks of plague in Austria, although they continued to occur within the Ottoman Empire. Over a stretch of land spanning 1,600 kilometers (1,000 mi), soldiers were posted within a musket shot of each other. Along this border, people and goods could only pass at designated areas and were held there to check for signs of plague.[7] People were monitored for 21 days unless a plague was active on the Ottoman side of the border. In that case, they were held for 48 days. To check that fabrics and wool were not infected, they were placed in a warehouse where peasants were given money to sleep on top of them. If the peasants remained healthy, then the goods were clean.

3 Whipping Yourself

In the ancient world, it was thought that plagues were caused by Apollo shooting people down with his invisible arrows. Indeed, it must have seemed as if some divine force was randomly afflicting only certain individuals as a plague spread. In the Middle Ages, however, it was not Apollo who was spreading disease. Instead, the Christian God was punishing people for their sins. Flagellants were people who thought the best way to rid themselves of sin was to punish their sinful bodies. Across Europe, large groups of people gathered together to whip themselves. In 1349, they arrived in London and put on quite the show of purification: Each had in his right hand a scourge with three tails. Each tail had a knot, and through the middle of it, there were sometimes sharp nails fixed. They marched naked in a file, one behind the other, and whipped themselves with these scourges on their naked and bleeding bodies.[8] That same year, however, Pope Clement VI issued a Papal Bull against the flagellants. They were taking the Church’s right to forgive their sins into their own hands. Also, having large groups of people assemble and spray blood around open wounds was a good way of spreading disease.

2 Mercury, Unicorns, And Goat Stones

The placebo effect is amazing. If you tell people that you are giving them a medicine to treat their condition, they often report that they feel better even if the substance contains no active ingredient. In fact, if you tell them that the medication is rare or costly, the effect becomes even stronger. Belief in a medicine is a powerful part of its potency. Early doctors may have unwittingly taken advantage of this when they prescribed exotic concoctions for their patients. In the ancient world, spices from distant lands were prized for their medicinal powers. In the 17th century, expensive drugs were still favored by those who could afford them.[9] Mercury, the only liquid metal at room temperature, was used by those amazed by its quicksilver properties. Others made much of crushed-up “unicorn horns”—probably the long, hornlike teeth of the narwhal. However, one doctor thought those were nonsense cures. He found that a little bit of bezoar (a stone found in the stomachs of goats and other animals) was just the thing for the plague.

1 Live Chickens

In the 17th century, one of the cures available to the doctor who liked bezoars involved snake flesh. It was used to make small lozenges that dissolved in the mouth. For these, he suggested rattlesnakes as the best source. But sometimes, it was live animal flesh that did the trick. The Black Death marked its patients with the formation of hugely swollen lymph nodes that turned black—hence its name. These buboes were exquisitely painful to the touch and a natural place for doctors to try out their cures. To heal the buboes, one Austrian doctor of 1494 offered a solution: Take some young roosters, one after the other, with the feathers plucked from around the hole in the backside. Place the rooster’s rump on the bubo until the rooster dies. Repeat with another rooster until one survives.[10] How the rooster was held in place until it died is not described. The treatment was used for many centuries and seems to have developed from an Arabic treatment for sucking venom from bites. In that case, a chicken was cut just above its heart and the wound placed over the bite. Top 10 Deadly Pandemics Of The Past