NYC was built from the southern tip up. A walking tour of Lower Manhattan is refreshingly rambling as its narrow streets predate the grid system imposed on the remainder of the island starting in the early 1800s. Consider the following a best-of history guide for the next time you’re in the Big Apple. 10 Fascinating Facts About New York City

10 Collect Pond

The area currently occupied by Chinatown’s Columbus Park sits atop what was once Lower Manhattan’s primary source of fresh water: the (eventually) aptly named Collect Pond. Before the Europeans, the Lenape Native Americans had a settlement along its shoreline. In the 1540s, the French established a fortified trading post on one of its lush islands. Starting in the early 18th century, the British used the pond alternately as a summer picnic spot and a winter skating rink. Around this time, however, Collect Pond took a turn for the . . . well, gross. A number of tanneries moved into the area. (Mulberry Street, which overlooked the pond, became known as “Slaughterhouse Street.”) By the 1800s, Collect Pond had collected enough waste that it was deemed “a very sink and common sewer.”[1] In 1807, the city started construction on a canal—modern-day Canal Street—that would funnel the polluted water into the Hudson River. A hasty drainage job left a marshy, mosquito-ridden landfill upon which wealthy slumlords built tenements for the poor, including many newly arriving immigrants.

9 The Five Points Slums

Built partially on land filled in over fetid Collect Pond and famously depicted in Martin Scorsese’s epic 2002 film Gangs of New York, The Five Points was loosely bound by Centre Street to the west, the Bowery to the east, Canal Street to the north, and Park Row to the south. The neighborhood’s name derives from a starlike confluence of two crossing streets and a third that terminates at their intersection, forming “points.” Those thoroughfares were Anthony Street (now Worth), Cross Street (now Mosco), and Orange Street (now Baxter). This guide[2] shows its approximate location today. The Five Points was the filthiest, most congested district in an already flighty, overcrowded Lower Manhattan. Living conditions were crammed and squalid. Shoddily constructed tenements on unstable, poorly drained ground quickly became dilapidated. The unsanitary, overpopulated conditions became breeding grounds for cholera, tuberculosis, typhus, malaria, and yellow fever. Worse, the problem fed upon itself as hundreds of thousands of overwhelmingly poor immigrants poured into New York annually, providing slumlords with a steady stream of desperate souls to exploit. Crime, organized and otherwise, was rampant. For most of the 19th century, The Five Points is alleged to have had the highest murder rate of any slum in the world. Prostitution and gambling reigned, including the gentlemanly sport of rat fighting. The Five Points and adjacent Lower East Side served as the backdrop for James Riis’s mesmerizing 1890 book How the Other Half Lives, which paved the way for safety, sanitation, and economic reforms throughout Lower Manhattan.

8 Castle Clinton

Before Ellis Island, there was Castle Clinton, the nation’s first official immigration processing center. The castle was first constructed due to the growing tensions between the United States and Britain in the early 19th century. The 28-cannon fort, which was garrisoned but never saw action during the ensuing War of 1812, occupied what was then an artificial island off Manhattan’s southern tip. The locale has a dark legacy. After the Lenape Native Americans refused to pay Dutch settlers taxes in the 1640s, the governor decided that a fitting penalty was slaughtering every man, woman, and child . . . and decorating Castle Clinton’s predecessor, Fort Amsterdam, with their heads.[3] The castle received its current name in 1815 in honor of outgoing NYC Mayor DeWitt Clinton. Upon becoming state governor, he led the effort to build the Erie Canal, a 584-kilometer (363 mi) engineering marvel connecting the Great Lakes to the Atlantic Ocean via New York’s Hudson River. No longer a military necessity, Castle Clinton became, in turn, a beer garden, exhibition hall, opera house, and theater before transitioning to an immigration center in 1855. It remained in this role until 1890. Then the immigration center was moved to Ellis Island. True to the Castle Clinton’s Lower Manhattan roots, many immigrants were cheated out of their possessions by corrupt workers, and some even died awaiting entry into the US. Its island now filled in and connected to the mainland, Clinton Castle still stands today at the southern endpoint of (what else) Bridge Street. Tours are readily available.

7 Fraunces Tavern

Up for a pint? Duck into the oldest bar in New York City: Fraunces Tavern at 54 Pearl Street. Constructed in 1719, the watering hole carries the name of Samuel Fraunces, who operated the establishment as the Queen’s Head Tavern during the 18th century. During the Revolutionary War, Fraunces and his tavern were part of a spy ring undermining the British occupation of New York. (The British held New York for nearly the entire war, necessitating an intricate web of espionage and sabotage terrifically depicted in the TV series TURN: Washington’s Spies.) Following the cessation of hostilities, George Washington held a farewell party at the tavern for high-ranking Continental Army officers. The joint also undoubtedly had its share of revelers on November 25, 1783, when the British formally departed the former colonies from nearby Evacuation Day Plaza. In 1789, Fraunces became newly inaugurated President George Washington’s first chief steward, overseeing the head of state’s household affairs. Fraunces died in 1795 while Washington was still in office. In recent years, Fraunces has become the center of a new controversy: his race. After being portrayed as white for centuries, many historians now believe he was a (free) black man.[4] In addition to operating as a bar and restaurant, Fraunces Tavern now features a museum dedicated to Lower Manhattan’s Revolutionary War era.

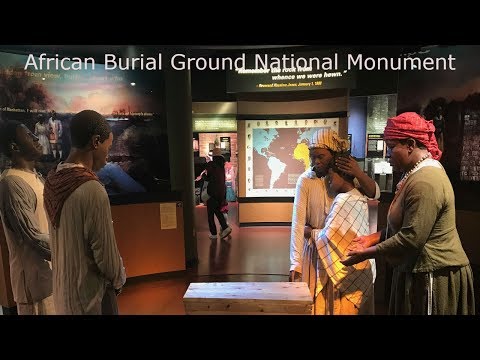

6 The African Slave Trade And Burial Grounds

Although slavery is typically more associated with the US South, New York City was the second-largest slave-owning city in the British colonies in America in the mid-18th century. (Charleston, South Carolina, was the biggest.) Ironically (and tragically), most of the macabre buying and selling of human beings transpired at a street now synonymous with commerce: Wall Street. At 74 Wall Street, a 42-story building housing luxury condominiums rests over what was once New York’s primary slave market. The “peculiar institution’s” history in New York is as old as the city itself. The first slaves arrived in New Amsterdam in 1626, just two years after the Dutch settled there. Slave labor was instrumental in building defensive structures for the small, vulnerable European population—including the wall for which the modern street is named.[5] Today, the only remaining evidence of the slave market is a plaque erected in 2015. However, nearby is the African Burial Ground Memorial, the oldest and largest known excavated burial ground in North America for persons of African origin. Unsurprisingly, blacks were not permitted to be buried in cemeteries alongside whites. Deceased African Americans, both free and enslaved, were relegated to mass gravesites. The memorial sits atop a site that went undiscovered until 1989, when preconstruction activities for a federal office tower found some 15,000 skeletons dating from the 1630s through the 1790s. Slavery was not outlawed in New York State until 1827. 10 Eerie Tales Surrounding Places Where Tragedies Took Place

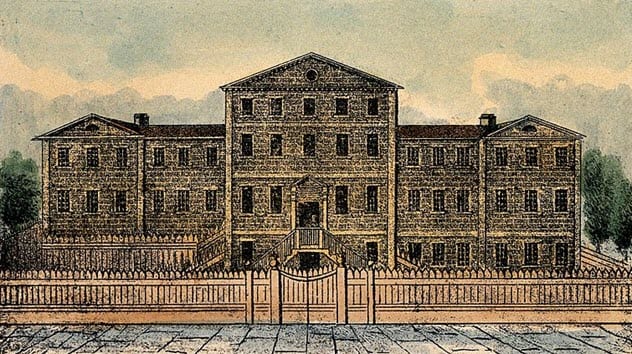

5 City Hall Park

The grassy grounds surrounding New York’s City Hall represent perhaps the only sizable patch of land in Lower Manhattan never to be fully developed. The original Dutch settlers used the area as a public commons. The space took a darker turn when the British seized the colony in 1664 and hosted public executions.[6] More death and despair followed. In 1775, the British began work on a prison named Bridewell. Soon, the American Revolution broke out in full force, giving the redcoats more pressing priorities than proper penitentiaries. The unfinished building—which even lacked windowpanes to protect from bitter cold winters—was a pit of suffering and death for hundreds of POWs until the war’s conclusion. In the years immediately preceding the war, the grounds became a popular spot for “Liberty poles,” erected to inspire insurrectionist spirits and often to signal covert conventions of anti-British conspirators. An 18th-century game of whack-a-mole ensued, with pro-independence groups like the Sons of Liberty putting poles up as fast as British soldiers could chop them down. The poles were figurative lightning rods that made bloody confrontation inevitable. In January 1770, British soldiers were attacked mid-removal by patriots. The subsequent skirmish on nearby Golden Hill, which preceded the Boston Massacre by several weeks, is where modern-day Gold Street gets its name. Along with a stone plaque, a 20-meter-tall (66 ft) replica of the sawed-off liberty pole was installed in 1921.

4 The Catacombs At Old St. Patrick’s Cathedral

The most famous burial ground in Lower Manhattan is undoubtedly the graveyard at Trinity Church at the intersection of Wall Street and Broadway. The cramped site is the final resting place of several famous figures, most notably Alexander Hamilton. However, another gravesite offers a much more immersive experience. At Old St. Patrick’s Church in modern-day SoHo—far humbler confines than the current polished behemoth in Midtown—visitors can tour catacombs where the city’s wealthier Catholic residents sealed themselves for all eternity.[7] Both the catacombs and the high wall in the adjacent church graveyard were intended to prevent something widespread in 19th-century Lower Manhattan: grave robbing. Understandably, avoiding post-death looting took some, well, loot, a price point that limited the catacombs to especially prominent New Yorkers. Several members of the Delmonico restaurant family are there, as is the man credited with bringing opera to NYC. One interment of interest is Thomas Eckert, who served in several capacities, including presidential bodyguard, in the administration of Abraham Lincoln. On April 14, 1865, Lincoln wanted Eckert for exactly that role while he took in a play at a Washington, DC, theater. Unfortunately, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton refused permission for Eckert to go. Allegedly, Stanton claimed that he had an important task for Eckert that night. Controversy remains about the real reason Eckert wasn’t guarding Lincoln’s viewing box when John Wilkes Booth assassinated Lincoln later that night.

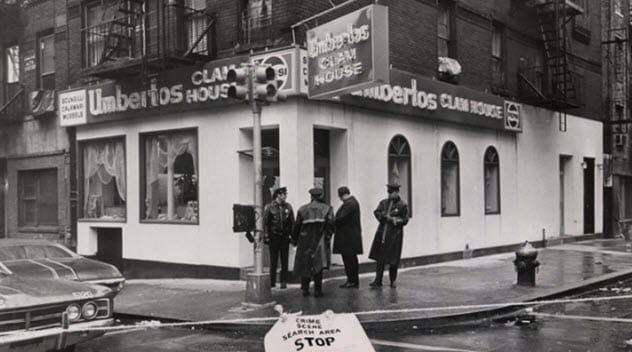

3 Mob Hit Hunting In Little Italy

Despite being a shell of its former self—its footprint has been severely compacted by Chinatown from the south and Nolita from the north, and its restaurants are now mostly tourist traps—Little Italy is still a great place to see where some high-profile mafiosi got whacked. At the famed Umberto’s Clam House at 132 Mulberry Street, Colombo crime family hit man Crazy Joe Gallo was enjoying dinner with his family, including his 10-year-old daughter. The date was April 7, 1972—Gallo’s birthday. Sometime during his second helping of shrimp and scungilli (not a bad choice for a last meal), gunmen entered the restaurant and opened fire. The shooting marked the first time a mobster was murdered in front of his family, so he must have made someone really mad. Another high-profile murder took place in the late 1930s at the site of the former ‘O Sole Mio restaurant, also on Mulberry Street. The grisly photo of an unidentified mob hit victim sprawled out on the street made headlines across New York. Unfortunately, the site now houses a tacky souvenir shop selling “I Heart NY” T-shirts to clueless tourists.[8] Slightly outside the boundary of Lower Manhattan, the Museum of the American Gangster at 80 St. Mark’s Place offers a deep dive into mob history.

2 The City’s Oldest Sites

New York is a city where the only thing constant is change. In fact, only one structure remains from the 1600s (its first century of European inhabitation): a cemetery. Coincidentally, it is the final resting place of the city’s first Jewish settlers. In modern-day Chinatown, the site holds 107 graves with headstones that have remained surprisingly legible. The cemetery was used at least through the American Revolution as it includes the remains of several fallen soldiers. The oldest surviving building is the aforementioned Fraunces Tavern, but many historians discount this distinction due to its series of renovations. The title of oldest original building goes to St. Paul’s Chapel, which dates to 1764. The house of worship includes a pew where George Washington prayed on the day of his presidential inauguration. Nearby, the Edward Mooney House was completed in 1789 and has served as a private residence, hotel, brothel, and saloon over its long history. At the turn of the 20th century, it was headquarters to an odd bloke named Chuck Connors, the self-proclaimed “mayor of Chinatown.” He led voyeuristic whites on slumming tours through the rowdy Bowery bars and Chinese opium dens. Notably, Connors once helped future legendary songwriter Irving Berlin get a waiting gig at a local restaurant. Today, the Chinese characters adorning the building’s second-floor facade showcase the staying power of Chinatown.[9]

1 Chinatown

Chinatown is the only substantial ethnic neighborhood remaining in Manhattan. Others like African-American Harlem, Latino Washington Heights, and especially Little Italy have long been whittled away by gentrification. For first-time visitors, Chinatown is simultaneously inviting and intimidating. Decrepit yet delicious dumpling houses, Eastern medicine pharmacies showcasing vast rows of herbal remedies, shops brazenly peddling dubiously authentic clothing and handbags, and cavernous dim sum restaurants—including the 800-seat, soccer-pitch-sized Jing Fong—line the narrow, typically crowded streets.[10] Chinese immigrants began settling in Lower Manhattan in the 1870s. As Easterners in a Western world who were viewed as “others” even by other new arrivals from Ireland, Italy, and Germany, the Chinese developed a necessary insularity further exacerbated by the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act. This limited the number of Chinese allowed to immigrate to the US. Like other ethnic groups in 19th-century Lower Manhattan, the Chinese formed violent gangs. Known as tongs, the gangs ran opium dens, prostitution rings, and gambling halls. One narrow Chinatown alley, the elbow-shaped Doyers Street, became notorious as the “Bloody Angle” for a deadly inter-tong battle that left several gang members dead. The killers escaped via another fascinating Chinatown anomaly: a winding series of underground tunnels used for illegal smuggling and quick getaways from law enforcement. Today, nearby Chatham Square offers the last accessible vestige of this tunnel network, known today as the Wing Fat Shopping Arcade. 10 Most Haunted Buildings In New York City And Their Backstories About The Author: Christopher Dale (@ChrisDaleWriter) writes on politics, society, and sobriety issues. His work has appeared in Daily Beast, NY Daily News, NY Post, and Parents.com, among other outlets. Read More: Twitter Website