10 The Tenere Tree

The Tenere Tree in the Sahara was the only tree for 400 kilometers (250 mi)—a pretty useful landmark in a desert. It stood alone for 300 years and probably sprouted when the desert wasn’t actually a desert at all. But the tree became the lone survivor from its childhood after a well dug in 1938 gave it a steady source of water and nourishment. Unfortunately, its proud stand against time and loneliness came to an abrupt end when a drunk driver managed to crash into the only obstacle for hundreds of miles. Despite the annoyance, most people are at least a bit impressed by the fact that he managed it. The trunk now lives in the Niger National Museum, with a metal sculpture taking its place in the desert. Hopefully, the next drunk driver will at least avoid the metal tree.

9 52 Blue

52 Blue is the world’s loneliest whale. While most whales vocalize (and hear each other) at a frequency of 10–39 Hz, 52 Blue calls at a frequency of 52 Hz, meaning that no other whales can hear him or even know that he’s there. Watch this video on YouTube Even humans haven’t seen the solitary whale. We’ve only heard his song on navy sonar detectors. It’s never accompanied by another whale call, and other whales won’t hear him even if he’s close to their pod. Although the whale has inspired documentaries, albums, Twitter accounts, and films, he wanders the oceans alone.

8 Toughie The Frog

Toughie is the last Rabbs’ fringe-limbed tree frog. When he dies, the species will be extinct. But he isn’t gliding through the rain forests of Panama or catching bugs from his favorite leaf. Toughie lives in a gray shipping container called frogPOD in Atlanta’s Botanical Garden. He does live there with 11 other rare species of frogs, but he’s the only one that’s definitely the last of his kind. The others were probably killed off by a fungal infection that’s killing amphibians around the world, which is why so many are living as endlings in labs instead of wandering the rain forests. The last female in his species died in 2009. Toughie stopped calling for mates shortly after he was taken into captivity. He never responded to recorded frog calls and must now know that there’s nobody out there for him.

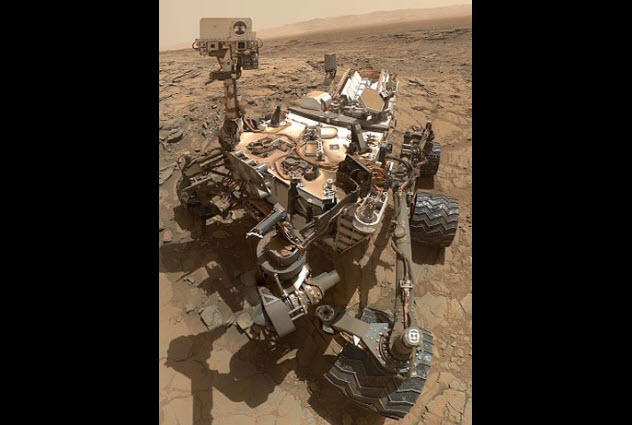

7 Curiosity Rover

Alone on a planet light-years from home, the Curiosity rover has spent almost four Earth years by itself in space. But that’s okay, right? It’s just a robot and doesn’t actually feel lonely or call for a mate that will never come. Except on its birthday every year, little Curiosity sings “Happy Birthday” to itself. He’s the loneliest little robot in the known universe. Try not to imagine the scene from WALL-E where he tries to hold hands with himself. That just makes it worse.

6 The Lonely Island Of Hashima

About 25 kilometers (15 mi) from Nagasaki, there’s an island that used to be home to over 5,000 people. Even when Hashima was populated, the island saw incredible brutality because conscripted civilians and prisoners of war were forced to work as slave laborers extracting coal from the mines there. But when Japan moved from coal to petroleum, there was no real point to keeping people on the island. So the coal mines closed down, and everyone who worked there moved away. After many solitary years, Google Street View was allowed to visit the site and take extensive photographs. Since then, the island has been opened up to tourists, but it’s still not home to a single resident. There are no plans to use it as anything other than a World Heritage site and a tourist attraction.

5 The Man Of The Hole

Imagine everyone from your family, friends, and cultural group dying out and leaving you alone in the world. Well, that’s what happened to the Man of the Hole. We know practically nothing about him or the people he used to share his life with. FUNAI (the Brazilian National Indian Foundation) first investigated the man after rumors surfaced about a lone man living in the forest. Nearby loggers denied sightings, but that could be because they were the ones who bulldozed his village in the first place. After declaring that he was the survivor of two separate massacres that wiped out his people, FUNAI declared that a 80-square-kilometer (30 mi2) piece of land around him was off-limits to developers. It was traditionally land that he had inhabited and therefore belonged to him as an indigenous person. Unfortunately, that declaration wasn’t enough to stop gunmen from attacking the Man of the Hole in 2009. Amazingly, he managed to survive the attack and, as far as anybody knows, still lives alone in the forest digging holes.

4 Lonesome George

Lonesome George, the last known Pinta Island tortoise, was around 100 at the time of his death. Instead of living out his golden years in some grace and reflection, he was constantly prodded by zookeepers to mate with females from other subspecies. That’s no easy feat for any tortoise, never mind one that’s a century old. Unfortunately, even when old George managed, the eggs didn’t hatch and everyone had to start all over again. He was finally released from those duties in 2012, and his remains were prepared through taxidermy for exhibition in a number of natural history centers. Unfortunately, there are now disputes about where he should be displayed as the last of his kind. So it could be quite difficult to go and see him.

3 The Last Baiji Dolphin

Baiji dolphins used to frolic in the Yangtze River system but were declared functionally extinct when nobody could find a single dolphin in its natural habitat in 2006. Luckily, in 2007, a Chinese man saw one by chance and took a video of him leaping on the surface of the river and generally not looking too worried about the whole extinction thing. Unfortunately, no other dolphins were seen with him, and scientists have recently stated that they think he’s the last of his kind. Watch this video on YouTube Even if there are others, a small population wouldn’t be genetically viable to bring these dolphins back from extinction. So scientists aren’t willing to update the status of the dolphins unless we find enough to create and maintain a decent number of genetically diverse dolphins.

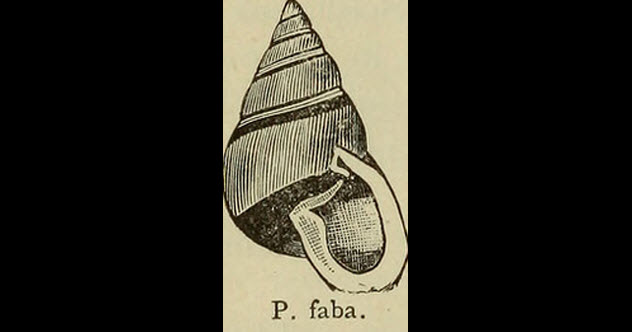

2 Solitary Escargot

You never really think of snails as being lonely, but being the last of your kind in a tank in Bristol would probably make anybody a bit lonesome. After being hunted and killed by a species of cannibalistic snails, the tiny Polynesian gastropods were moved to Bristol for a new start. Hopefully, there will also be a bit of a boost in their numbers because they won’t be mercilessly pursued and eaten by their own kind. The Partula faba—a species so weird that they don’t even get a non-Latin name—were extinct in the wild by the time that breeding was attempted in Bristol. Eventually, they all died except for one last snail, another endling with no name. Unfortunately, she died in February 2016 with no hope of continuing the odd species of air-breathing, tropical land snails.

1 Humans

That’s right. Even though humans have frequent communication on a day-to-day basis, loneliness is now thought of as the next public health issue. With approximately 30 percent of people over 80 saying that they’re lonely, the latest studies have shown that men whose wives died recently have a 25 percent higher chance of dying within a decade than other men. Loneliness has an actual biological impact on people’s health, aging, and life span. Unlike George, Toughie, and Curiosity, we’re not the last of our species or alone on a desolate planet. But loneliness still affects a huge number of us. The media blames a variety of things—Facebook, the fact that a quarter of us live alone, and the stigma of admitting to loneliness. But it looks to be the next epidemic, affecting people of all ages in all social structures. Given that loneliness in humans increases the risk of death by over 25 percent, we need to decrease the number of people who feel lonely. At the moment, 10 percent of people in the UK “get lonely often” and 48 percent of people think that we’re still getting lonelier. Valerie is a fiction writer and marketing copywriter in London, UK. She obsessively makes lists on her phone, and this is just an extension of that.