SEE ALSO: 10 Viral Photos That Were Proven To Be Hoaxes

10Sinbad’s Death

Famed stand-up comedian Sinbad is very much alive—but back in March 2007, some prankster decided to edit Sinbad’s Wikipedia page to claim he had died of a heart attack. Sinbad first learned of the inaccurate information in a telephone call he got from his daughter, and he expected it not to be that big of a deal—but over the next couple of days, hundreds of concerned people contacted him about his presumed death. He said the incident wasn’t “that strange”, though, and, given the large smattering of celebrities who have also been the victims of premature obituaries thanks to Wikipedia vandalism (everyone from Ted Kennedy to Miley Cyrus), he just might be right.[1]

9 Wrightbus

Here’s a case in which a “prank” addition to a Wikipedia article created widespread panic because of a tense environment. In November 2015, a vandal added an erroneous statement to the Wikipedia article for Wrightbus (a bus manufacturer based in Ballymena, Northern Ireland) that claimed FirstGroup, a Scotland-based transport company, had purchased Wrightbus. The false information was quickly spread by word-of-mouth, panicking the company’s more than 1500 employees. It gets worse, though, because two significant businesses (a tire manufacturer and a tobacco company) had recently announced plans to leave Ballymena, costing more than 1700 jobs between them. The hoax was a match in the powder barrel for local workers who were already concerned about job loss. While the hoax was quickly discredited by a local newspaper, that only stopped the bleeding—it couldn’t heal the wound.[2]

8Jar’Edo Wens

This case shows just how easy it is to compose a faux article that slips through the cracks and stays on Wikipedia for years. That’s what happened to an article created in May 2005 for a fake deity known only as Jar’Edo Wens (most likely a clever reworking of the name Jared Owens). The creator of the article made just three Wikipedia edits: besides creating the page, he also added Jar’Edo and another made-up deity, Yohrmum (an obvious pun) to a list of Australian aboriginal deities. The entire process took just eleven minutes to complete, but the Jar’Edo Wens page—despite being flagged in 2009 for lacking sources—stayed on the website for nearly ten years. During that time, Jar’Edo even found his way into a book criticizing theism, being mentioned as a god who had “fallen out of favor.” When the hoax was finally outed in March 2015, it was officially recognized as the longest-running hoax on Wikipedia. Though it’s since been surpassed in that respect, the “Jar’Edo Wens” debacle was definitely a key moment in the history of Wikipedia hoaxes.[3]

7 Maurice Jarre

Our next entry proved that Wikipedia isn’t always the problem. Back in March 2009, Academy-Award-winning composer Maurice Jarre died. Quotes that appeared in several obituaries for him (including one published by “The Guardian”, a leading British newspaper) included “life itself has been one long soundtrack,” and “when I die there will be a final waltz playing in my head that only I can hear.” The problem? Jarre never actually said any of that. You see, when University of Dublin student Shane Fitzgerald heard of Jarre’s death, he thought it an excellent opportunity to test how the media used Wikipedia in an age of instant news. It took him less than fifteen minutes to make up a quote and add it to Jarre’s Wikipedia page. He expected newspapers not to use the quote because it wasn’t linked to any source other than Wikipedia. After the fabricated quote became widespread, however, he admitted his “crime” out of fear the quote would be forever attributed to Jarre. Instead of blaming Wikipedia for allowing the quote to spread, he blamed journalists, who, he said, write articles too quickly to verify sources, adding that Wikipedia moderators had removed the faux quote from the site multiple times within hours of it first being posted.[4]

6 Bicholim Conflict

This entry showcases what is likely the most effort ever put into perpetrating a Wikipedia hoax. A group of editors on the site created a 4,500-word article all about a 17th-century war between Portugal and India—that never happened. The story was so convincing that Wikipedia granted it “good article” status, an honor granted to less than 1% of articles on the site. The creator of the hoax even nominated the page for “featured article” status, a privilege reserved for the best articles on the site, although the committee responsible for choosing featured articles noted that some of the article’s key sources were “weak” and ended up not selecting it. What they didn’t realize is that nearly every source used in the article was a nonexistent book, and the only mentions of a “Bicholim Conflict” on the internet linked back to the Wikipedia article. The fake history might never have come to light if amateur wiki-detective “ShelfSkewed” had not decided to double-check the article’s sources, leading to the unraveling of the elaborate hoax.[5]

5 Orange Julius

Some Wikipedia hoaxes are just not believable. For instance, in June 2005, an article appeared on Wikipedia on the creator of Orange Julius (a popular fruit drink similar to an orange Creamsicle). On the surface, the article seemed in order: just a short biography of Julius Freed, featuring sections on his early life and his creation of the Orange Julius. It also mentioned his other “ingenious” inventions, such as the inflatable shrimp trap and the portable pigeon bathing unit. Wait … what? Amazingly, this obviously fake section of the article didn’t get fact-checked until “Jeopardy” legend Ken Jennings discovered it. He set to work disproving the hoax and then posted the results on his personal blog. Nobody was hurt by the little white lie, although, hilariously, Orange Julius briefly ran an ad promoting Freed’s (faux) accomplishments before Wikipedia removed the hoax.[6]

4 Coati

Back in July 2008, Dylan Breves, a seventeen-year-old student from New York City, edited the Wikipedia article for the coati (a tropical American mammal). The only thing he altered was adding “Brazilian Aardvark” to a list of the creature’s nicknames. Why? While on a trip to the Iguazu Falls (a system of waterfalls in Brazil), Breves and his brother had misidentified coatis as aardvarks. Breves told “The New Yorker” he does not like “being wrong about things”, so he inserted the false nickname “as a joke.” Like many other minor wiki-vandals, he expected Wikipedia to remove his entry for a lack of sources, but, in a bit of circular reporting, an article in “The Telegraph” used Wikipedia as its source, and Wikipedia later sourced the claim using that same “Telegraph” article. From there, references to coatis as Brazilian aardvarks quickly spread, appearing in several major newspapers as well as a book published by the University of Chicago.[7]

3Edward Owens

Don’t confuse him with Jar’Edo Wens! Edward Owens was a fictional pirate created by students at George Mason University as part of a 2008 course on “Lying about the past” taught by Professor T. Miles Kelly. The students created a website, videos, and, of course, a fake Wikipedia article to promote the hoax, which stated that Owens was an oyster fisherman who turned to piracy as a method of survival during “The Long Depression”—an economic slump in the late 1800s. After several blogs (most notably one connected with “USA Today”) reported the hoax as a factual historical account, the perpetrators admitted their deceit—but that did not stop Kelly from teaching the class again in 2012. This time, the students masqueraded as “Lisa Quinn”, a woman who thought her uncle was a serial killer based on some odd items she found in a trunk that had belonged to him. The students found four fairly similar cases of women murdered in New York City between 1895 and 1897, and created (factual) Wikipedia articles for them. The plan was that Lisa would then discover their names in her uncle’s documents, and the internet would believe it had unmasked a serial killer. Everything was going fine—until the students posted the hoax to Reddit, at which point it took just 26 minutes for someone to call foul, guessing the post was “viral marketing.” This led to the story being quickly picked apart by a bevy of eager Redditors, who pointed out, among other things, that the Wikipedia articles were new and the documents appeared artificially aged.[8]

2 John Seigenthaler

In May 2005, an editor—like many other hoax creators, identified only by an IP address—created a Wikipedia article stating, among other falsities, that journalist John Seigenthaler was a suspect in the murders of both John F. Kennedy and Robert F. Kennedy. In fact, Seigenthaler was one of Robert’s closest friends as well as a pallbearer at his funeral. The article wasn’t discredited until November 2005, when a friend of Seigenthaler spotted it and forwarded it to him. Seigenthaler described the incident in “USA Today” as “internet character assassination”, and described the perpetrator of the hoax as having a “sick, twisted mind.” The controversy made national news and marked one of the first times the media asked serious questions on how reliable sites with user-generated content really were. Finally, in December, a 38-year-old deliveryman named Brian Chase revealed himself as the author of the hoax, saying he posted it because he had thought Wikipedia was “some kind of ‘gag’ encyclopedia”.[9]

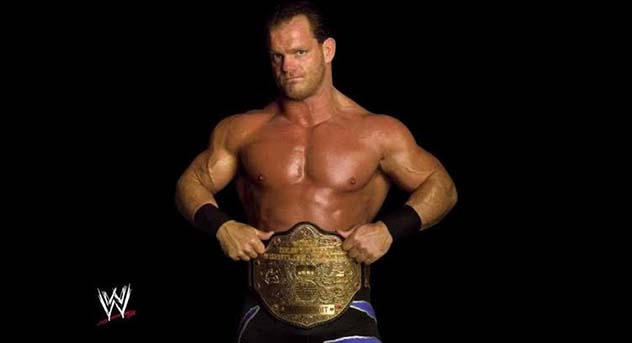

1 Chris Benoit

Back in June 2007, Canadian WWE wrestler Chris Benoit killed his wife, his son, and himself in a grisly double murder and suicide. About fourteen hours before police discovered the crime had taken place, a Wikipedia editor based in Stamford, Connecticut (about three miles from WWE headquarters), had edited the Wikipedia page for “Chris Benoit” to speculate that Chris had no-showed a WWE event because of “the death of his wife Nancy.” The mysterious editor (a 19-year-old wrestling fan who had a history of vandalizing Wikipedia articles) later gave a long apology on a Wikinews forum dedicated to the controversy, saying it was an “incredible coincidence” based on “rumors and speculation” he had found on the internet, and “the comment wasn’t meant to be a prank.” Police interviewed him and coerced him to cooperate with their checking of his computer equipment. The lesson here? No matter why you want to do it, don’t vandalize Wikipedia. Just don’t.[10] About The Author: About The Author: Izak Bulten is an animator and amateur film historian who loves writing articles about conspiracy theories, pop culture, and “crazy-but-true” stories. He’s created logic puzzles for World Sudoku Champion Thomas Synder’s blog, “The Art of Puzzles“, and the e-book “The Puzzlemaster’s Workshop”. More recently, he’s been writing animation news for his blog, “The Magic Lantern Show“.