Original title: You Sane Men, easier to find as Bloodworld. The problem with Janifer is that he was, well, a hack. He wrote professionally for fifty years. Pick up any given Janifer book and you will probably be disappointed. Although, he did garner a Hugo nomination in 1960 as the co-author (under the pseudonym Mark Phillips) with Randall Garrett for Brain Twister, a novel that thankfully did not win. However, in the blind-pig-finds-an-acorn model, Janifer knocked the ball out of the park with Bloodworld (to mix a couple of metaphors). Essentially, the fine ruling menfolk on a colonized planet remain “sane” and capable of fulfilling their social obligations by torturing underclass women as a recreational activity. For its time, it was definitely provocative and probably an intentional attempt to write a “shocking” novel. Still, the torture scenes are painted with a nicely consistent “this-is-normal-and-right” tone… until the protagonist develops feelings for one of his whipping-lasses, and the morality play starts. Gene Wolfe fans are especially encouraged to check this one out.

Anyway, our down-and-out anti-hero protagonist finds himself shipped off to a desert world and deeply in debt. The planet is owned and managed by a “family company” for the production of their one great monopoly… dragonhides. The critters, not real dragons but might as well be, are big nasty reptiles living in the desert sands, and their skins are nearly indestructible. A skinner goes out (with his gear and supplies brought from the company store and increasing his debt, of course) and does his best to kill these beasties without getting killed himself so he can haul the skins back. The company even has a nursery where they hatch and raise baby dragons, and that work is deadly, too. Throw in rival factions within the family controlling the company, and you have a fairly-straightforward adventure that could well have been set in a 1890s coal town. But it isn’t, and the dragon-work is interesting to read. It’ll never be a classic, but Skinner is satisfying genre-stuff.

Another hack, but a true pulp-fiction hack. Will Jenkins wrote thousands of short pieces under a variety of pseudonyms for such genres as westerns, romances, jungle adventure, horror, radio scripts, etc plus what he is best-known for — science fiction under the nom Murray Leinster. His short story “First Contact” is in the Hall of Fame anthology, as it should be. If it is remembered long enough, it may well be exactly how our ships and those of the aliens manage not to fight when first encountering one another in the depths of interstellar space. But the vast majority of Leinster stuff is uninspired, and that is being kind. The Greks Bring Gifts is an exception. The title (sic; one e not two in Greks) is a play on the Trojan Horse myth. What we have is this large spaceship with aloof, somewhat creepy Greks in it coming to earth. They are a schoolship for spaceworkers, and they have a class of likable, furry Aldarians aboard. Might be a good learning experience for them to make contact with a new race, the humans. Oh yes, the Greks will give us what technology they can that might help us, free of charge. Just the neighborly thing to do. And almost unlimited broadcast energy is the biggie to us humans. Why build more internal combustion cars when pretty soon everyone will have a broadcast-powered car? So sorry, the Greks must be on their way now, but things will work out, you’ll see, all of these current economic difficulties notwithstanding. And about the Aldarians….

William Sleator is a name unfamiliar to many adult science fiction fans, yet he has made a living for 30+ years writing fiction that is mostly of a sci-fi nature. However, it is young adult science fiction. Not Spaceship Under The Apple Tree style “kiddie sf” — more along the lines of Heinlein juveniles, though with far less science. Podkayne of Mars rather than Rocketship Gallileo. But stylistically completely different, as Sleator specializes in weird moods and bizarre situations. House of Stairs, written in 1974, is truly weird and definitely a bizarre situation. While I haven’t read the entirety of Sleator’s science fiction output, this novel is — pardon me — light years beyond the other works of his I have read. It’s really hard to provide a synopsis that isn’t a spoiler for the new reader’s freakazoid reaction to what transpires, but I’ll try. Understand that the following is as bare-bones as possible, on purpose. A group of adolescents who don’t know one another awake to find themselves in a strange place. Stairways and landings ramble everywhere in three dimensions, and that is all they see. It’s chilly, and there is no food or water. Then, on occassion, they get fed some nutrient bars by machinery. That’s all I’m saying about the plot. The book really makes you realize that you’re pretty normal, because you would have to consider whether this book is appropriate for other people’s precious little snowflakes to read and because of a concept I can’t mention without spoiling. But apparently no one has a problem with this book.

Hal Clement was the quintessential old-school “hard” science fiction author. In fact, most of his novels are probably unreadable to the majority of today’s science fiction readers because of voluminous passages coming across as graduate-level lectures in physics and exobiology. Even fans of the new revival of science in science fiction, as typified by the justly popular works of Robert J. Sawyer, may find Clement books to be a perfect cure for insomnia. But, as befitting a longtime professor of chemistry and astonomy, the science is as genuine as possible for its time periods, meticulously worked out, and free from errors. Clement garnered fame and critical acclaim for 1954’s Mission of Gravity, a novel about humans directing intelligent centipede explorers on a high-grav world (where a fall from three feet near the poles is certain death) to retrieve readings from a crashed probe near the equator where the gravity is much less extreme. So much for the classics…. Iceworld features far less science than his other works — though there is no escaping science in a Clement book. We see the alien viewpoint even more than the human one in this tale of intergalactic drug smuggling. The drug is tobacco, the only drug the aliens have ever found which results in full-blown do-anything addiction from a single dose. The “Iceworld” is Earth — to the aliens, anywhere water can be a liquid is unbelievably cold. Excellent character portayals of both humans and aliens, and altogether an absorbing read. Note: none of the above is much of a spoiler — it’s the set-up.

Creator of the famed Travis McGee series, McDonald is considered by the world to be a mystery writer. As a Grand Master award winner, he certainly is that. But McDonald was a first-rate science fiction author as well. His numerous SF short stories, sold to magazines, consistently show fine craftsmanship and an understanding of the genre… they never disappoint. One could do worse than to pick up his seminal collection, Other Times, Other Worlds. Of his three longer science fiction works, Ballroom Of The Skies is probably the best. Heavy on sometimes stilted dialogue in the beginning, and using more exposition in the latter stages as the characters become involved with greater events, the novel essentially explores the fundamental question of why humans seem driven towards war and self-imposed disaster, even as their other activities strive towards bettering living standards and the human condition. Of course, there is a sinister explanation….

I hesitated to place this book on the list, because Foster fans are legion. Thus, lots of people have probably at least heard of this book, even if they haven’t read it. It garners its place largely because many other works by Foster are so well-known it seems that this one has been largely ignored except for a minority of people like me who have accorded it cult status. It might well be the best alien biosphere ever described. The planet is all jungle, towering to dizzying heights of chlorophyll fecundity with a hellish swampy twilight at the surface. Human descendents of a long-ago spaceship crash live in the “mid” levels of the world, hence the title. At first glance they are primitive savages, but their ability to survive in a truly inimical environment has made them far more intimately familar with their surroundings than any Native American culture ever was. Then, a corporation illegally arrives on the planet to exploit its lush plant life for medicinal purposes. Our hero (considered rash and a weird-thinker by his tribe) along with his furcot — a native companion who can speak and has a much closer relationship to man than our dogs — agrees to guide two stranded scientists back to their treetop base. Spectacular depictions of alien lifeforms. A “live with the rainforest, don’t exploit it motif,” which succeeds without pissing off political conservatives like me (no mean feat, that). And a revealed secret that makes the otherwise worthwhile pure gold.

Spinrad is quite well-known, especially for his 1969 novel Bug Jack Barron, which was a precursor to cyberpunk. Agent Of Chaos (1967) is his second novel. I hope too many eyes don’t roll to the back of too many heads when it is stated that this can only be described as political science fiction. Those who detest politics can still enjoy it, as the backdrop is Heinleinien space opera at its finest. But politics do take center stage, and one could even say that meta-politics is the theme here. So we have a totalitarian government (the Hegemony) and an underground rebel conspiracy (the Democratic Movement). The latter professes to work for individual liberty. But as these factions struggle, the Agents of Chaos — known to the public as the Brotherhood of Assassins — often intervene with random acts of violence that could favor the Hegemony on Tuesday and the Movement on Thursday. Just what is their agenda? The reader learns early on that their agenda truly is Chaos, but for definable political reasons which are slowly revealed. Central to the book is the concept of entropy, even in political systems. The Hegemony strives for Order and elimination of randomness, so of course a reaction occurs (the Movement) to challenge that move towards order. But the Agents have other ideas. Wait till you learn what the Agents consider to be the Ultimate Chaotic Act!

William Tenn was the pseudonym of Penn State professor Philip Klass. In the 50s and 60s, he wrote tons of science fiction short stories for Galaxy and Astounding. Almost universally, those stories were humorous and/or satirical, written in a breezy, fast-reading style. The majority have been reprinted countless times in various collections over the years. Yet, he wrote only one true science fiction novel: Of Men And Monsters. And even that one is somewhat short and easily read in a single sitting. But it is excellent and quite original, even though its premise sounds like standard fare. Gigantic mantis-like aliens have conquered earth and set up living quarters in equally gigantic houses. But scattered remnants of humanity survive, literally living like mice in the walls of the alien homes. And like mice, they must brave death in order to steal food. The true grace of the book is its development of the tribal culture(s) mankind adopts under these trying conditions. And of course, there is a rebellious spirit in our protagonist… leading him to upset the human social order.

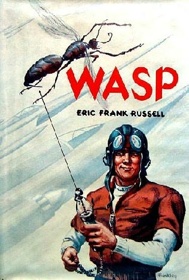

Russell himself is under-appreciated by today’s science fiction community. But he was, in fact, the favorite writer of both legendary editor John W. Campbell and author Alan Dean Foster (source: conversation between the two, as described by Foster in his introduction to The Best of Eric Frank Russell). Some of Russell’s short stories are held in high regard — “Allamagoosa” and others have been reprinted over and over, and in hall of fame or other “greatest of all time” anthologies. His novels… not so much. Wikipedia reports that a recent blip in interest has been seen over Wasp as a result of a reprinting in 2000, and the subsequent events of September 11, 2001. Because, you see, our protagonist employs effective terrorist tactics… which are depicted in the book with dark humor combined with more than tacit approval. Government approval, in fact. Spoiler alert: Wiki’s plot synopsis is essentially a complete outline of the book in paragraph form! Anyway, Wasp, written in 1957, is short and just outright fun to read. The title refers to the fact that the seemingly inconsequential can have disproportionate results — an example is given of a wasp which distracts a driver to cause a multi-car crash, thus tying up lots of manpower and money to deal with the aftermath. James Mowry becomes a government-trained wasp, dropped alone in disguise on an enemy planet during a fierce war with earth. Actually, this is somewhat similar to the Allies dropping solo paratroopers behind German lines in WWII, with instructions to sever communications, work with the underground, and generally make pesky nuisances of themselves. Which in the book Mowry does with derring-do, close calls, a contempt for authority, and witty if dark humor. The tricks and tactics he employs really make the book sing (a few simple stickers are amazing in their effect). Combine that with a character who detests the authority of his own government but figures that of the totalitarian enemy to be worse, and it should be a classic rather than a barely-known.