Pink is not even a “real” color, and some have called it a scientific enigma.[1] It is not a wavelength or particle and does not appear in the visible spectrum (it doesn’t exist in rainbows, for example). We can observe pink not because it actually exists, but rather because our brains perceive that it exists. Trippy. While that mind-bending reality sets in, consider these instances of pink appearing in nature. Pink is not a color often associated with nature, so these occurrences are all the more spectacular because of the rarity of their color in the natural world.

10Pink Sand Beach, Bahamas

Looking like a scene out of a technicolor fairytale, Pink Sand Beach stretches along three miles of Harbour Island in the Bahamas.[2] Just out to sea, an extensive reef system keeps the water calm and protects the beach and its visitors—but it is also the source of the sand’s bubblegum hue. The reef coral is home to a microscopic single-celled organism called Foraminifera, whose shells are bright pink or red. These coral insects are critical to the ocean environment, feeding on coral reefs, sea floors, under rocks, and in caves. But, like all living things, Foraminifera die, and when they do their colorful bodies are crushed in ocean waves and washed ashore. Mixed with the sand and other bits of coral, the Foraminifera give Pink Sand Beach its eponymous color.

9Female Orchid Praying Mantis

Like many insect species, the male and female orchid praying mantises of Southeast Asia have evolved to look very different from each other. The male is small and brown while the female mimics the visual appearance of the orchid flowers around which they live. This camouflage allows the females to attract insects as prey and allows the males to avoid detection while they look for a mate.[3] The result of this species’ evolution is a truly extraordinary female specimen. Female orchid mantises have perfected the art of masquerade. Their limbs are shaped like petals and sport spectacular pink and yellow hues. With bodies that look like fully formed orchids, they are easily mistaken for the real thing and can actually be better at attracting insects than the flowers they mimic. This is despite the fact that orchid mantis females do not mimic any particular species of orchid, but rather a generic combination of orchid-like features.

8San Francisco Salt Ponds

If you have ever traveled to San Francisco by airplane, you may have noticed a brightly colored patchwork of ponds on the coast below. These are the Cargill Salt Ponds, which have now mostly been sold back to government and non-profit landowners for restoration.[4] For 150 years, salt was one of the city’s primary industries. The salt mines, which covered more than 15 thousand acres, now comprise a massive tidal wetland restoration project. This means the brilliantly colored ponds will not be there forever. So why did the salt mines create such a colorful landscape? It’s all thanks to a microorganism, a type of algae called Dunaliella. High salt content in water causes the algae to grow into a deep red or coral pink color. In low salt content, the algae grow green. The remarkable color array of the salt ponds is even noticeable from space; astronauts have used them as a visual marker while orbiting the planet.

Unfortunately, because the dolphin eats the fish that river fishermen want to harvest for a living, the animals are often deliberately killed. They are also the source of many myths. Local legend says the dolphins are quiet, solitary, and blind, but scientists have shown that they are in fact sociable—even quite aggressive—and have full vision. The dolphins range from gray to the pink hue that they are known for, and scientists have observed that the pink color emerges as the animals age, with male dolphins having the rosiest coloration. One working theory is that the pink of their skin is scar tissue from the frequent fights the grown dolphins engage in. Others have guessed that the pink coloration is an evolved response to blend in with the red sand in the riverbeds of South America, in order to hide from larger predators.[5]

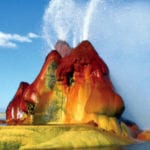

6Lake Hillier, Australia

From the sky, Australia’s Lake Hillier looks like someone emptied several vats of Pepto Bismal onto the landscape. It’s strikingly pink. The source of its color is the same algae found in the salt ponds of San Francisco: the salt-loving Dunaliella microbe. It has pigment compounds that make it particularly good at absorbing sunlight, which helps create the reddish-pink color. Scientists have found a mix of other algae and bacteria that have helped intensify the pink color of Lake Hillier. These discoveries also point to the reason for the lake’s coloring—the additional microorganisms are evidence that the lake was home to a leather tanning station in the early 1900s.[6] So, this particular example is half natural, half manmade; the lake’s color is particularly vibrant because of human activity.

5Elephant Hawk Moth

From caterpillar to fully-fledged moth, this species is a fascinating one. Its name is derived from the appearance of the caterpillar: a slimmer head and thorax than the rest of its body makes the caterpillar look like an elephant trunk.[7] However, like many moth caterpillars, it has evolved to disguise itself with markings that impersonate a snake, eyes and all, in order to fool potential predators into staying away. It even has a trick to mimic the blinking of an eye; the caterpillars have a growth called an anal horn that can palpitate rapidly to look like a blinking eye. If the caterpillar can survive and make it to the cocoon stage, it will emerge as one of the prettiest moth species on Earth, and certainly one of the most distinct moths in its native United Kingdom. Unlike many moth species, which are typically gray or brown, the Elephant Hawk Moth is pink and olive-coloured. They are often mistaken for a pink butterfly, but they are nocturnal and have stout, fuzzy bodies, like most moths.

4Pink Terraces of Lake Rotomahana

This is one pink natural wonder you can’t currently see—it is submerged from view. The terraces were thought to be completely lost in an 1886 earthquake off the shores of New Zealand. The terraces, which were both pink and white, were a natural wonder treasured by New Zealanders. Some even called them the eighth wonder of the world. They were utterly unique: the two largest formations of fine quartz on earth. One terrace outcrop was white, while the other, due to some undetermined chemical impurity, was pink. Fast-forward 150 years to an expedition to map and study the floor of Lake Rotomahana.[8] Scientists using sonar to map the lake floor discovered an outcropping they suspected could be the lost pink terrace. They sent an underwater camera team to be sure, and they confirmed that there were still small areas of both the white and pink terraces in existence. At less than ten percent of their former size, the terraces were indeed greatly diminished by the 1886 earthquake, but New Zealanders can take heart that these natural wonders are not completely lost to the world.

3Pink Katydid

Katydids, which are similar to crickets, are often green, but new research shows that in North American katydids, pink is the genetically dominant hue—the one that determines the coloring of offspring.[9] For decades, scientists believed that pink—as well as yellow and orange—coloring in katydids was the result of a genetic mutation controlled by recessive genes, the absence of the usual pigment of green, almost like albinism in humans. In the last decade, researchers at New Orleans’ Audubon Butterfly Garden and Insectarium have found new insights that show the opposite to be true. They have shown that green is, in fact, a recessive trait while pink is a dominant trait. This means that if a green and pink katydid mate, the offspring will be pink—not green, as earlier theories stated. The rarity of the pink katydids is attributed to the lack of camouflage offered by the bright coloration, compared to the green coloration. If you’re keen to see one in the wild, head to the New Orleans area, where there is a Cajun saying: “If a pink katydid lands on your shoulder on Valentine’s Day, you will find true love that year!”

2Lake Retba, Senegal

The picture-perfect white beaches of Lake Retba in Senegal are not as perfect or inviting as they seem. Lake Retba is so salty that it rivals the infamously salty Dead Sea, and its white beaches are mostly pure salt. Its nickname, Lac Rose, is a hint to its dry season coloring: a stunning shade of pink. (Its waters are continually changing color throughout the year due to salinity.) The source of the pink hue is the same as other pink bodies of water in the world: the algae Dunaliella.[10] Mix up a cocktail of algae, minerals, and hot sun, and the lake can even appear blood red at certain times of the year. The lake is a hub for salt collectors, who spend full days mining salt from the lake bed and have to slather themselves in shea butter to protect their skin from the high salinity.

1Okinawa Cherry Blossoms

Cherry blossoms are a crowd-pleaser in several areas across the world, including Vancouver and Washington, D.C., but there is no better place to see the pinkest blossoms than Okinawa, Japan. It is the first area in Japan where cherry trees bloom, around mid-February, while the rest of the country sees blossoms closer to April and into May. In Japan, the cherry blossoms are revered. During the cherry blossom season, picnickers flock to orchards across the country to engage in hanami, which translates as “looking at flowers.”[11] So why are cherry blossoms so revered in Japan? Their short-lived bloom echoes the Japanese cultural heritage of valuing the fleeting nature of beauty. Cherry blossom season also represents new beginnings, coinciding with the new school year and new financial calendar in Japan: April 1. Plus, they are just breathtakingly beautiful.