Unique photos, autobiographies, and workplaces also invite an intimate look into what it was like to be enslaved. Slavery artifacts have a weird side, too—like the Bible designed to make workers more obedient and the reverse engineering of an escaped slave’s DNA.

10 Mystery Foundations And Box

Virginia’s College of William & Mary is centuries old. In 2011, an excavation was launched south of the college’s iconic Christopher Wren Building. Historic documents recorded nothing in that area. However, after shoveling through a shallow amount of dirt, the team unearthed mysterious foundations. The brick layer once supported a building 4.9 meters (16 ft) wide and over 6 meters (20 ft) long. A relatively small size for a building today, this one dated to the colonial era when it was considered large. The structure was likely the living quarters or workplace of the 18th-century enslaved staff. If not lodgings, the building could have been a laundry room or kitchen. Additionally, near the foundations was a box buried for unknown reasons. Made of slate, it measured 15 by 10 centimeters (6 by 4 in) and was empty, save for deteriorated grains that could have been anything.[1]

9 The Last Slave Ship

The Clotilda was the last slave ship of the United States. Her human cargo was not even legal. By the time the vessel sneaked into Alabama waters, the importation of slaves was banned. Timothy Meaher was a plantation owner who did not care for humanitarian laws. He made a $100,000 bet that he could bring a boatload of African slaves into the country without being detected. In 1860, Meaher employed William Foster to sail over to the Kingdom of Dahomey (modern-day Benin) and kidnap 110 people. Meaher and Foster succeeded and burned the Clotilda to destroy the evidence. Historians have looked for the vessel ever since. In 2018, the strongest candidate was tracked down by a journalist. The shipwreck was near Mobile, Alabama, which was already a thumbs-up. When the Dahomey captives were freed five years after their capture, they built their own town north of Mobile. Structural clues also placed the vessel’s age in the mid-1800s. (Clotilda‘s construction year was 1855.) Additionally, the 38-meter-long (124 ft) ship showed fire damage, but more research is needed to confirm its identity.[2]

8 A Crucified Slave (Maybe)

In 2007, archaeologists excavated at Gavello, a site outside Venice, Italy. They found a skeleton buried in an unusual way. At the time of his death around 2,000 years ago, Romans buried their dead in tombs and with grave goods. This man was plonked into the ground with neither. When researchers examined his feet, they found one ankle was missing. The other had unhealed fractures, suggesting the injury occurred right before death. The nature of the wounds strongly suggested that a metal spike had been forced into the foot. One possibility was that his heels had been nailed to a cross.[3] Ancient Romans reserved crucifixion mostly for slaves as well as some criminals and those who threatened the status quo (Jesus). Even though the Romans crucified people for centuries, the Gavello grave is only the second time that evidence of the practice turned up in the archaeological record. The skeleton belonged to a man in his thirties. His small body suggested that he was an undernourished slave. The unceremonious burial also matched the disdain shown for those who were executed.

7 Heming’s Kitchen

Former US president Thomas Jefferson loved French cooking. At the time, French meals needed a certain stove that was exceptionally rare in the United States. In 2017, a kitchen with the right stew stoves was found. Discovered at Monticello (Jefferson’s plantation in Virginia), the room was undoubtedly the realm of James Hemings. Born into slavery, Hemings was taken to France with Jefferson when the latter served as the US minister to France (1784–89). The 19-year-old Hemings trained as a French chef and, upon his return, introduced macaroni and cheese, meringues, and creme brulee into American culture. The first thing archaeologists found was the kitchen’s original brick floor in a cellar. As the work continued, the ruins extended to a partial fireplace and the four stew stoves, which would have stood waist-high during Heming’s time. Sadly, only their foundations were left. Even so, the find marked a rare time when a workplace was linked to an enslaved person whose name was known.[4]

6 The Sierra Leone Smoker

Around 200 years ago, a slave smoked a pipe at Maryland’s Belvoir plantation. The pipe was one of four among other artifacts that remained at the site until archaeologists unearthed them in 2015. The pipe was made of clay, a fortuitous choice for researchers. Clay is porous and can retain bodily fluids such as saliva from a smoker. DNA tests soon identified that the person who enjoyed tobacco in this case was a woman. Experts did a deeper analysis and found that she shared strong genetic links to modern-day Sierra Leone—more specifically, to the Mende people of West Africa. Indeed, old records revealed that a slavery route once existed between Sierra Leone and Annapolis, where the Belvoir plantation was situated.[5] The smoker was either abducted from West Africa or born in America to parents taken from Sierra Leone. The pipe proved that artifacts could identify slave quarters, which often cannot be separated from small housing for white families. The item is also part of an initiative to use artifacts’ DNA remnants to return to descendants their ancestral heritage, which was erased the moment their ancestors landed in America.

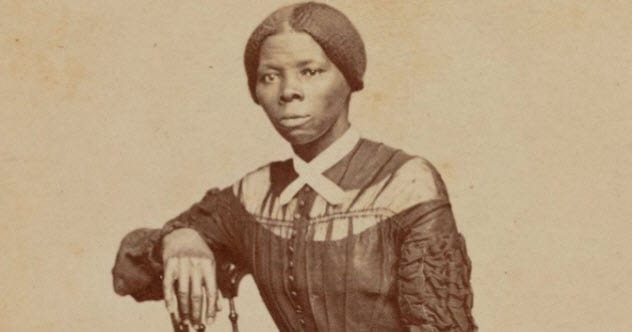

5 A Young Harriet Tubman

Harriet Tubman escaped slavery and then risked her life to free hundreds through the Underground Railroad. All of Tubman’s photos showed an older lady, stooped and fragile. When researchers recently uncovered an unknown portrait of a young Harriet, they were stunned. Not only did it depict her in earlier years, but her famous grit shone through. The picture was taken in her forties around 1868 or 1869, with Tubman’s gaze as the most striking feature. It burned with a tangible mix of strength and suffering. For the first time, scholars could see why people called her “Moses,” for leading her people to safety, and “General Tubman,” after she helped to free over 700 African-Americans in a Union raid. The image came from an album that once belonged to abolitionist Emily Howland, who was Tubman’s friend. All 49 portraits were of men and women, black and white, who fought for the freedom and education of enslaved individuals. The album contained another gem—the only known image of John Willis Menard, the first African-American elected to the US Congress.[6]

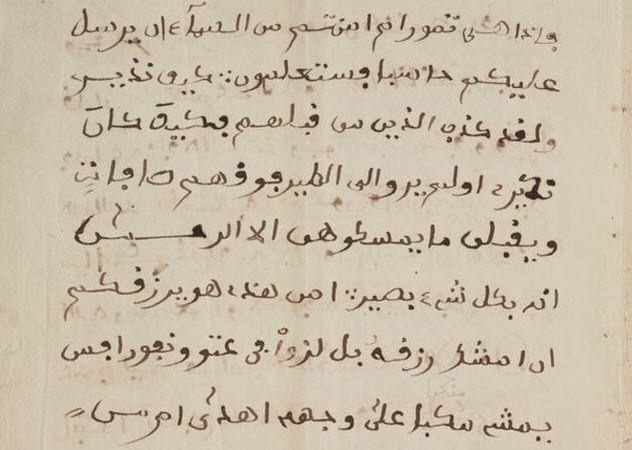

4 Unique Slave Narrative

Omar Ibn Said was a wealthy young Muslim in the 19th century. Living in West Africa, he dedicated himself to being an Islamic scholar. One day, he was plucked from his routine and transported halfway across the world. Said was sold into slavery in Charleston, South Carolina. His first owner was cruel, and after an escape attempt, Said was imprisoned in North Carolina. Contrary to popular belief, slaves were not uniformly illiterate. Said carved Arabic script on the only surface available—the cell’s walls. It was also his autobiography, which ensured his personal story would survive. The Owen family purchased Said, and he lived with them until he died. He experienced a relatively good life, during which he produced the 15 pages that described his abduction and enslavement. Today, the document is invaluable as a rare story sourced directly from the victim. (As it was penned in Arabic, his owners could not edit it.) It remains the only known Arabic slave narrative created in the United States. In 2019, the Library of Congress digitized Said’s pages to bring them to a wider audience.[7]

3 George Washington’s Teeth

One of the wackiest myths surrounding George Washington is that he wore wooden dentures. However, Washington never chewed his corn with timber teeth. By the time he was president, he had already lost most of his own teeth and had several sets of dentures—some sporting other people’s pearly whites. Evidence seems to suggest that they came from slaves. In 1784, he recorded the purchase of human teeth for his own private use—“By Cash pd Negroes for 9 Teeth on Acct of Dr. Lemoire.” The latter was a dentist who treated Washington and also paid premium prices for people to part with their front teeth. Slaves could also sell their teeth but for much less. While it is impossible to know if the nine snappers became dentures, they were almost certainly pulled from Washington’s slaves. It is believed that the two men struck a deal to use Washington’s own slaves to drive the price down.[8]

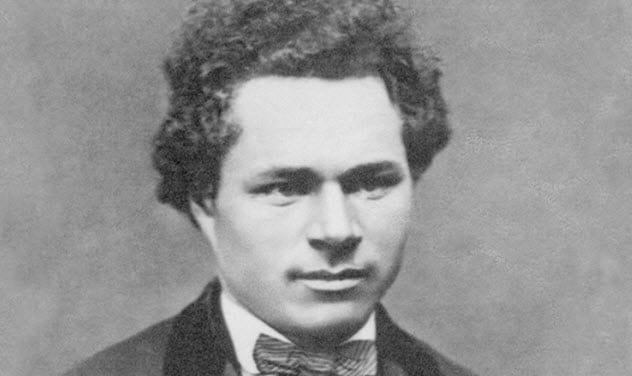

2 Hans Jonatan’s Genome

In 1784, Hans Jonatan was born in the Caribbean. His family was enslaved on a sugar plantation in St. Croix, which was a colony of Denmark. When Hans was old enough, he was shipped to Denmark and ordered to fight for the Danish navy. At one point, he was told to go back to the colony, but the 18-year-old made a bid for freedom. In 1802, he fled to Iceland and became the first person with African heritage to reach the region. In recent years, scientists performed the first study using DNA from descendants and genealogical records to partially recreate the genome of an ancestor whose body was not available. They analyzed 182 of his descendants and reverse engineered their genes until they completed 38 percent of the genome on his mother’s side. It showed that she was originally from Cameroon, Nigeria, or Benin. After comparing the genes to world databases, they also revealed when things changed drastically for the family. Hans’s mother or her parents were captured in West Africa between 1760 and 1790.[9]

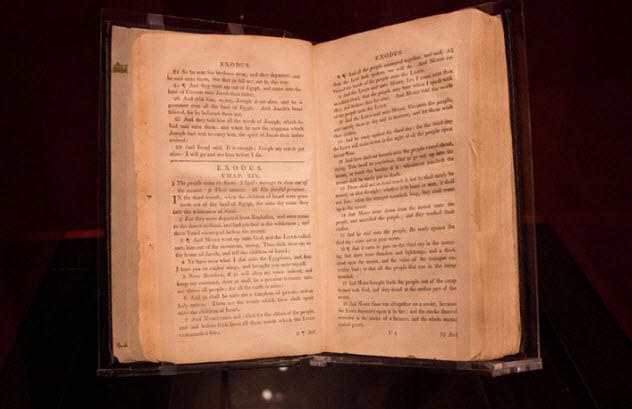

1 Rare Slave Bible

When slaves in the Caribbean opened their first Bible, it was not a regular edition. What British missionaries brought in the 19th century was a version so snipped that it shocked modern people. In 2019, one of the last three remaining slave Bibles went on display in Washington, DC. Visitors were so stunned by the abridged book that officials soon made it the centerpiece of the exhibition. Roman Catholics can page through 73 books, the Protestant edition holds 66, and 78 books knit together the Eastern Orthodox translation. The Caribbean version was pruned to 14 books.[10] The missionaries wanted to convert enslaved Africans to Christianity. However, they first had to get permission from the sugar plantation owners who did not want their workers reading about rebellions and uprisings. For this reason, related passages were removed. In this version, the enslaved Israelites never left Egypt. Lines that condemn slave owners are gone. Even though “their” Bible praised obedience to a master, the Caribbean’s enslaved people constantly rebelled and finally gained freedom in 1834. Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages