We tend to think of ancient civilizations like those in Rome and Egypt as holding all our historical secrets. We look to the landmasses in Europe, the Americas, the Middle East, and Asia for even more archaeological clues. But islands with a lot of foot traffic in the past can also hold missing pieces from history as well as extinct cultures and unusual graves.

10 The Temple Of Artemis

Lost temples may be cliche movie fodder, but in real life, archaeologists diligently hunt them. One temple has eluded shovels for over a century. The search began when the geographer Strabo (first century AD) described a great temple dedicated to the goddess Artemis. Following Strabo’s directions, archaeologists began excavating near the ancient site of Eretria on the Greek island of Euboea. All efforts since the 19th century were in vain. Then in 1964, a team found something that made them realize that Strabo had been mistaken. They found a Byzantine church containing material taken from an older Greek structure. The stones made archaeologists reconsider Strabo’s advice that the temple was 1.5 kilometers (1 mi) from Eretria. Instead, they calculated the more likely distance of 11 kilometers (6.8 mi).[1] In 2012, they discovered a possible temple gallery at the bottom of a hill at the village of Amarynthos. It was not until 2017 that the walls were breached to reveal the sanctuary of Artemis. A positive identification was made after writings and coins bearing her name were found, along with an underground fountain and buildings from the sixth to the second centuries BC.

9 The Dolphin Grave

During medieval times on the islet of Chapelle dom Hue, somebody gave a dolphin a Christian burial. In 2017, archaeologists worked on the 15-meter-long (49 ft) islet in the English Channel when they found a human grave. But inside the tomb, which had been made with considerable effort, were the bones of a dolphin (possibly a porpoise). An archaeological first, it made no sense. Literature about the time gave a clue—people had dined on preserved porpoise. Perhaps it was a preservation pit packed with salt, and for some reason, the animal was never retrieved. While there were signs that the creature had been butchered, the pit was a precise replica of others found in medieval cemeteries. The islet was possibly a monks’ retreat in the 14th century, and no other remains have been found except the bizarre burial.[2]

8 Evolution In Action

On the island of Daphne Major in the Galapagos, something incredible happened. For the first time, scientists watched a new species form in the wild—within two generations. Biologists noticed one mysterious arrival, a large cactus finch (Geospiza conirostris) native to other Galapagos islands. The male courted two indigenous females, both medium ground finches (Geospiza fortis). As their scientific names suggest, the groups share a similarity. They belong to about 15 species called Darwin’s finches. The romance produced fertile chicks, which was unusual. Hybrids happen among animals from the same groups (big cats, equines), but such offspring are sterile or struggle to reproduce. Despite being fertile, the hybrids had a different song and beak shape, which did not win them mates among the ground finches. So, they interbred. In their fourth generation, a drought hit the island in 2002–03. Only a brother and sister survived. After the drought, they had 26 kids.[3] The species, confirmed by genetic tests, proved to be resilient. In 2012, researchers counted eight breeding pairs and 23 singles.

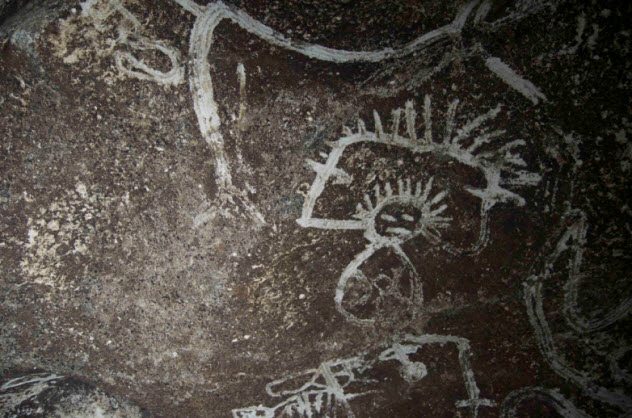

7 Caves Filled With Extinct Beliefs

After the Spanish landed on the Caribbean island of Mona, they eradicated the local Taino people’s culture. When archaeologists recently found cave art, it provided a precious chance to at least glimpse their spiritual beliefs. The now-abandoned island had another surprise—the art was pristine depictions before the Spanish arrived. The images lined narrow caves which took researchers three years to investigate. They revealed what the culture wanted to preserve: Animals, human figures, and faces adorned with headdresses were among thousands of pictographs. Some were scraped or rubbed into the walls, which had a thin surface. The figures became more distinct once the design scraped off the top layer and showed a different color mineral underneath. Other images were painted. Their choice of pigmentation is also not completely understood. Normally, ancient painters used obvious materials like only charcoal and ocher. Not the Taino. Complex paints were uniquely blended for each cave. The ingredients included charcoal, plant materials, minerals, and bat droppings. Researchers have a theory about why they ventured into uncomfortable spaces for hundreds of years (13th–15th centuries). The Taino believed that the Sun and Moon rose from beneath the ground, which made the artistic spelunking a sacred activity.[4]

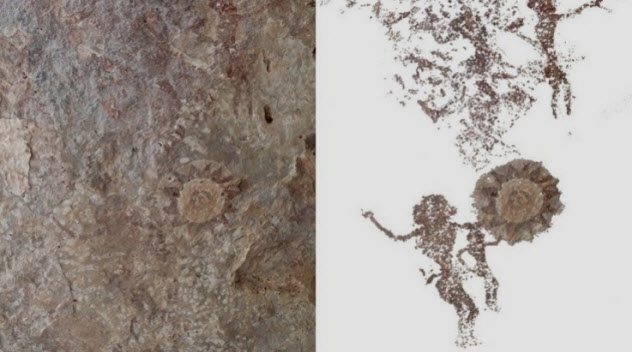

6 Galleries Of Miniatures

In 2017, archaeologists explored a tiny Indonesian island called Kisar for the first time. They found they were not the first humans to set foot on the 81-square-kilometer (31 mi2) patch. Kisar was covered with cave paintings in at least 28 locations. The art was thousands of years old and, intriguingly, quite small. The expressive images measured 10 centimeters (3.9 in) and included boats, horses, dogs, and human figures holding different items. Their size and style link them to ancient art found on the neighboring island of Timor. This revealed that the two locations probably shared a closer bond than previously believed. The age of the miniatures is not established with certainty. But the oldest could be 3,500 years old when new settlers brought domesticated animals such as dogs. Some of the younger images could have been made when trade brought metal drums from Vietnam and China to the area about 2,500 years ago. Among the myriad of tiny paintings are people playing similar drums. They also resemble some of the figures that decorated the imported instruments.[5]

5 Rediscovery Of Kane

The island of Kane, which is mentioned several times in ancient records, was once home to a city with the same name. In 406 BC, the famous Battle of Arginusae occurred nearby when the Athenian army defeated the Spartans. Any historian would love to set foot on this island, but for a long time, nobody could find it. In 2015, the entire missing island was rediscovered in Turkish territory. However, it was no longer an island. In the past, it was one of triplets called the Garip islands. But in the two millennia that followed, enough sediment stacked up between Kane and western Turkey to form a peninsula. The island never truly disappeared—it merely joined the mainland. The settlement was identified after scientists had a closer look at local underground soil samples. That was when they discovered that the two existing Garip islands had a third member and that it was now part of the peninsula. Pottery pieces and architecture as well as other artifacts also helped to positively confirm the location of the city.[6]

4 Female Fishermen

In 2017, archaeologists opened a grave on Alor Island in Indonesia. Inside, they found fish hooks arranged around a woman’s face. The burial was remarkable in two ways. It produced the oldest burial fish hooks, fashioned from snail shells around 12,000 years ago. In turn, this discovery dismissed the theory that fishing was an activity reserved for the islands’ men. Researchers now believe that at least some women cast their lines and brought home the hake. The five hooks adorned the woman’s chin and jaw. Four were moonlike crescents, and the last resembled a “J.” There was no protein source on the island other than what the sea offered. This made fishing an integral part of the community.[7] Sparing the hooks for the burial suggested that they also believed it would help the woman hunt in the afterlife. If this is indeed the case, then this is the most ancient society where fishing was viewed as a necessary activity for its members, both alive and dead.

3 Egyptian Tomb In Sudan

In northern Sudan, Sai Island is surrounded by the waters of the Nile River. Excavations in the 1970s found 24 tombs. Since Sai Island is among the largest in the Nile Valley and had an ancient gold mine, more graves were predicted. But it was not until 2015 that the most intriguing one was unearthed.[8] Around 3,400 years old, a big tomb held the remains of 13 men, women, and children. After two years of careful study, the tomb was identified as belonging to Khnummose. He was found in a chamber with a woman who was likely his spouse. The rest were found in another room. The tomb was built when Egypt controlled the region (1550–1292 BC), and Khnummose probably worked in the gold industry. Due to the bad state of the bodies, it is difficult to determine if Khnummose was an Egyptian born on Sai or a Nubian who adopted the culture. The burial included amulets, funerary figures, and Khnummose’s golden death mask. Whichever his ethnicity, he saw himself as Egyptian and this allowed a valuable look at the culture of Sai during that time.

2 Unusual Sunstones

Late in 2017, the archaeological site of Vasagard delivered a mystery. Located on the Danish island of Bornholm, Vasagard was likely a Stone Age temple connected to solar worship. Recently, over 300 stones were discovered buried at the site. Archaeologists recognized them as solsten or sunstones. Already known from nearby sites, most of the artifacts showed carved images of the Sun. Among the 5,000-year-old pebble batch were the usual sunny pictures. Then, two entirely new kinds showed up.[9] The “field” stones showed fields or grain. Others depicted what resembled a spider’s web. The exact purpose of all the stones remains unsolved. But the clues point to many uses instead of just one. Some stones, appearing shattered and scorched, were found in ditches and could have been burial items. Others were worn down, as if kept in pockets for a long time. These could have been amulets or a type of currency. A field stone was probably a charm or ritual ingredient to ensure a healthy harvest. Either way, the new images have enriched what researchers know about the local worshiping of deities.

1 New Murder Island Mass Grave

One of the most horrific accounts of mutiny involves a passenger ship that sank in 1629 off Australia’s west coast. The Batavia hit a reef, and 282 passengers and crew made it to Beacon Island. But mutineers raped and murdered most of the survivors, including women and children. For this reason, it earned the title “Murder Island.” Excavations began in the 1970s, and graves revealed the stomach-churning violence that brought an end to many. For example, one man had the top of his head sheared off by a sword. In 2017, for the first time, a mass grave with a difference was found. Unlike the other burials, done in haste and with victims thrown in, the five individuals rested in a row. They had been respectfully arranged among artifacts. Also, no violence marred the bones.[10] Researchers believe that the victims died from dehydration soon after reaching the island and before the mass killings began. This adds a new paragraph to what really happened in the days following the Batavia‘s sinking. It also offers an opportunity to compare the new discovery with journals written by the Batavia‘s captain, who eventually rescued the remaining passengers from the mutineers. Jana also writes adventure books. You can visit her Smashwords page here. Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages