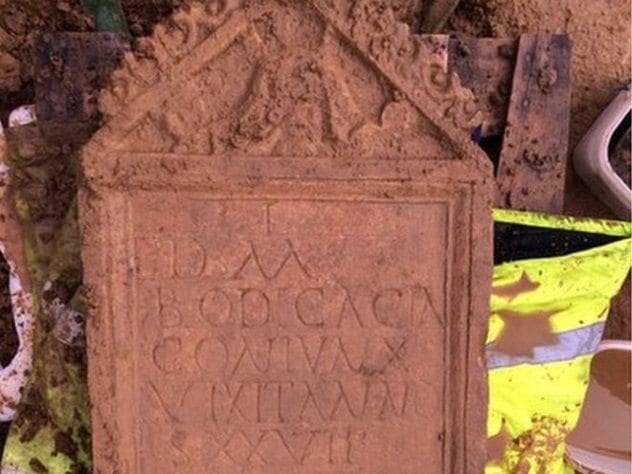

10 The Oceanus Tombstone

A mysterious and unique headstone turned up in an unusual place in England. The rare artifact was found resting facedown in a graveyard in Cirencester, Gloucestershire. Discovered in 2015, the tombstone’s front is inscribed: “To the spirit of the departed Bodicacia, wife, lived for 27 years.” That an inscribed Roman tombstone, probably dating to the second century AD, survived in England is noteworthy. Over time, most were removed and reused in construction projects. Only ten have been found in Cirencester, and less than 300 have been found in Britain. The odd location—a graveyard—is viewed as such by archaeologists since almost no gravestones were left at a tomb site. However, this one, depicting an image of what appears to be the sea god Oceanus, is not in a normal position. It was found in a grave, used like a protective slab over the deceased and not as the person’s standing headstone. Whether the skeleton underneath is Bodicacia, or her stone was pilfered to be used in the Cirencester grave, is unknown. Either way, it’s the first from Roman Britain to bear the mustached deity.

9 A Superstar Recruited Soldiers

In 2002, the base of a statue was found, covered in Greek, in the ancient Roman city of Oinoanda in modern-day Turkey. When it was translated nearly a decade later, the carving turned out to be an 1,800-year-old epitaph. It told an unexpected tale. The man being honored was named Lucius Flavillianus, a highly regarded veteran of wrestling and a brutal fighting sport called pankration. Needing recruits for the Roman army, the city used a smart but little-used tactic for the time: They asked the popular athlete to inspire new soldiers to sign up. He delivered so many young men to the army’s doorstep that after he died, Flavillianus was rewarded with supreme, hero-like status. Every community was ordered to erect a statue in his memory, and Oinoanda’s Flavillainus statue once stood on the base discovered in 2002. Researchers aren’t sure if the champion fighter joined the military himself or why he did such a dedicated job, but it’s likely that he was motivated by honor and the attention it brought him.

8 First Major Shipyard

Excavations at Portus in Italy had turned up several ruins. Archaeologists knew that the site was Rome’s maritime center during the first through sixth centuries AD and had hoped to find a heavy-duty shipyard, something from the Roman world that had never been found before. Over the years, they located warehouses, an amphitheater, a lighthouse, and even a palace. Over a decade passed. The team pressed on because ancient writings and a mosaic indicated there was once shipbuilding at the port. When the mammoth ruins of a rectangular building were found in 2011, they were mistaken for yet another warehouse. Further digging soon revealed that the football field–sized building had piers as well as eight garage-like bays that led into the Tiber river. These findings screamed “shipyard.” The bays ran about 60 meters (200 ft), ample space for ships to be repaired or constructed. While the building’s position, size, and structure support the theory that it’s the first major Roman shipyard ever identified, one element remains missing. If ramps for launching ships can be found, then it would undoubtedly confirm the yard as the biggest of its kind in the Mediterranean. During its heyday, the shipyard stood five stories tall.

7 Arieldela

For four years, two archaeology professors led a student team at ‘Ayn Gharandal in Southern Jordan. They didn’t realize that they were digging into a patch of Earth that everybody had been searching for. In 2013, they expanded their investigations of an old Roman fort when they found the gate of the ruined complex. The arched structure had long since collapsed, but a single block revealed the answer to a mystery. Inscribed in Latin were words that still showed traces of red paint. The unexpected find was also decorated with victory symbols, such as laurels and a wreath. Phrases dedicated the fort to four Roman emperors who ruled together from AD 293 to 305. Furthermore, the stone named the Second Cohort of Galatians as the infantry unit stationed there. The title rang an immediate bell with those at the site. Ancient military documents indicate that the unit arrived in Israel to suppress a Jewish revolt in the second century AD. The unit was said to have had a stronghold at a place called Arieldela. Nobody could pinpoint where Arieldela was, until the gate stone surfaced at ‘Ayn Gharandal.

6 A Referee’s Mistake

Around 1,800 years ago, a Turkish-born gladiator died because of a referee’s decision. The sad tone of his gravestone read, “Here I lie, Diodorus the wretched. After breaking my opponent Demetrius, I did not kill him immediately. But murderous Fate and the cunning treachery of the summa rudis killed me.” The tombstone shows Diodorus standing over his submissive opponent, looking expectantly at the referee (summa rudis in Latin) to declare him the winner. This deviates from normal burials, which typically provide a gladiator’s stage name and how many times he won or lost during his career. The unique tombstone focused on Diodorus’s death both visually and with a written account. Researchers believe that the referee thought Demetrius had fallen accidentally and fatally ruled that the match could continue. The image adds to a growing belief among scholars that gladiators didn’t merely butcher each other. Granted, Diodorus perished, but he didn’t kill his opponent when he had the chance. Instead, he expected a third party to call the victory. If gladiator combat wasn’t a disciplined sport, there would be no need for referees.

5 The Batavian Jupiter

In 2016, archaeologists browsed a field in the Netherlands. The site in the province of Gelderland was about 80 hectares of pure discovery. The 6,000-year-old haul included an engraved tombstone, a funerary urn, and 2,500 bronze artifacts. The discovery of Roman items wasn’t really a surprise. Gelderland once bordered Roman territory, so that was to be expected. What wasn’t anticipated was a statue of the god Jupiter and a unique ointment pot. Such elite objects would be more at home in a wealthy city or religious center than the area where they were found. During the artifacts’ time, the land was occupied by mainly Batavian farmers, who lived in humble houses made of wood and mud. This revealing glimpse about the Batavians could mean that the locals were more Romanized than previously believed. To explain the out-of-place possessions, experts have two theories: Either the owner was a rich Batavian who wanted to display his wealth in a Roman manner, or perhaps the settlement had a temple honoring the deities of Rome.

4 The Empire Was Infested

How much a community is at risk of parasitic infections hinges mainly on good sanitation. The Romans were famous for their advanced sanitary system. They had public baths and toilets, plumbing, and aqueducts that provided drinking water. To see how the Romans measured against less sophisticated nations, anthropologists toughened up and inspected ancient poop in 2,000-year-old latrines in 2015. Contrary to what one would expect, the results showed that Roman citizens battled with parasites. Internal infection was rife, especially whipworms, tapeworms, and roundworms. More surprisingly, it was worse than before they developed their famed sanitation. The problem stemmed from a lack of knowledge about worms. Ancient Romans didn’t understand that cooking killed the parasites and rampantly consumed a raw (and sometimes tapeworm-carrying) fish sauce called garum. Sharing communal baths with infected individuals was also risky. Farmers might also have used the human waste carted from the cities as fertilizer and infected their crops that way. Doctors also believed that worms formed spontaneously and treated patients with useless techniques like bloodletting and diets.

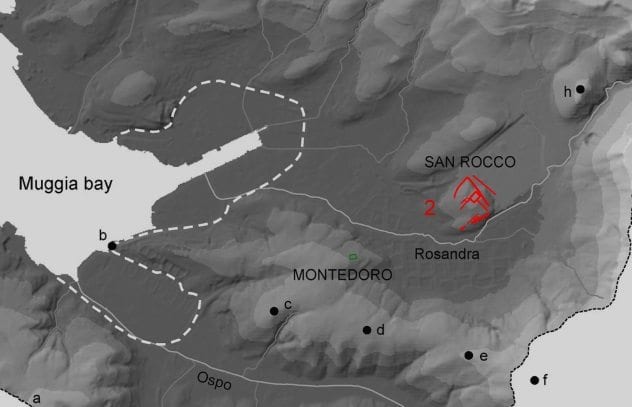

3 San Rocco

Researchers in Northeastern Italy hit upon the historic remains of an ancient fortification comprised of multiple buildings. The main fort, called San Rocco, was flanked by two smaller establishments on either side. Remarkably, the trio dates to around 178 BC. This makes it the oldest known Roman fort in the world, by several decades. San Rocco is the only example of an early Roman fort found in Italy and one of only a few in the world. By putting together its history, researchers hope to one day understand the evolution of what became one of the mightiest military nations on Earth. The construction of the fortification coincides with a time when the early Romans lost a war with a northern people referred to as “pirates.” The impressive size of San Rocco showed their determination not to lose a second time, and they eventually conquered the Istria peninsula in 178–177 BC. They also protected a settlement that grew from the San Rocco site called Tergeste, which later became the city of Trieste.

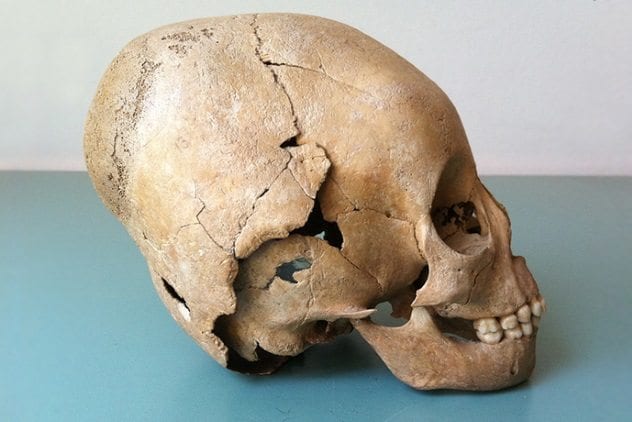

2 Friendship With The Huns

Considering that the Huns, under Atilla’s reign, started the destruction of the Roman Empire in the fifth century, this one came as a surprise. A 2017 study found that during the same century, farmers of both nations, who shared contact near the Roman Empire’s eastern border, actually got along. By studying skeletal remains, researchers could determine that they swapped crops and lifestyles in order to adapt to volatile and uncertain times. This was smart. Instead of fighting, they helped each other to survive. At first, the Huns had animals for milk and meat and grew various crops, while the Romans ate wheat and vegetables. Chemical analysis of the human remains showed that sharing eventually led to a diet which included just about everything on both sides. This mixed community, which lived near the Danube River in Hungary, allows a fresh view of the Huns, who never made it into the history books except as marauders. Elsewhere, people were Romanized, but in this case, some Romans incorporated the local customs, including the practice of elongating their skulls.

1 The Winged Building

A curious structure once stood in Norfolk, England. The large building, which resembled a “Y,” was raised around 1,800 years ago but matches nothing seen before from the Roman Empire. The oddity begins with a central room that leads to a rectangular chamber, with two extensions forming the so-called “wings.” The central room’s foundations were solid, but those of the chamber and wings were weak. The shoddy foundations indicate that this section was intended to be used for a single event. Most likely, it could only support timber and clay walls topped with a grass roof. The central part probably had a tiled roof as well as more sturdy mortar and was meant to be permanent. The winged part was eventually removed, and a more elaborate replacement was erected over it. The decorated postholes of this newer building can still be seen today. What the strange building was used for remains a mystery. While a villa nearby could mean the complex was Roman, it doesn’t fit any known design—and Roman architects stayed within a strict set of architectural forms. The building doesn’t match the characteristic style of the ancient locals, the Iceni, either. Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages