Today, Bulgarian soil is rich with their ruins and treasures. Some artifacts have been found nowhere else. Even the depths of Bulgaria’s Black Sea and islands are filled with unusual finds.

10 Bulgaria’s Last Aurochs

Today’s domestic cattle descend from a dangerous wild bovine. Called aurochs, they could weigh a hefty 1,100 kilograms (2,425 lb) and had lethal horns to match their tempers. The species itself died out in Poland in 1627 and was already considered extinct in Bulgaria since the 12th century. In 2017, excavations at the famous Rusocastro Fortress turned up animal bones from medieval times (13th–14th century). Between domestic and other wild creatures were the slaughtered remains of aurochs. By then, the once-plentiful wild cattle’s population was thought to have shrunk to Poland, Belarus, and Lithuania.[1] The remains at Rusocastro can now add Bulgaria to the territory of medieval aurochs herds. They also appeared to have been extensively hunted despite not being an easy game to kill. The large fortress’ population consumed a lot of wild meat, which made up around 25 percent of the bone cache.

9 A Chariot With Horses

In 2008, a team of archaeologists found a chariot buried in ancient Thrace (modern Bulgaria). Made of wood, it was not alone. Two horses had been buried in front of it as if to pull the vehicle. There was also a dog. A year later, they found the owner of the lavish burial. Near the chariot was a brick tomb. Inside was a man who had been buried roughly 1,800–2,000 years ago. Grave goods suggested that he was a Thracian nobleman or leader. He wore armor-type clothing and rested between gold rings and coins as well as a silver cup bearing the image of Eros, the Greek god of love. The chariot, plated with bronze, would have carried scenes from Thracian mythology, but these have long since faded. This kind of ancient burial is frequently found in Bulgaria. The elitist tradition began as early as 2,500 years ago and peaked during Roman times (2,100–1,500 years ago).[2] Chariot burials were a thing in other Roman territories as well, but none matched the enduring popularity they enjoyed in Thrace.

8 Mystery Arrow

Bulgaria may be liberally sprinkled with chariot burials, but every now and again, a simple and mysterious grave appears. In 2017, museum workers excavated the Antiquity Odeon in the city of Plovdiv. The Romans built it to host art performances. Among the remains of the Antiquity Odeon, the team found a grave. Thanks to medieval ceramics found in the upper layers, the find was dated to the 11th–12th centuries. It contained a person of unknown gender with an arrow in its chest. Unfortunately, the bones had become jumbled throughout the years. This made it difficult to determine what the arrow was doing there. One possibility is that the weapon was ceremonially placed on the deceased’s chest, a known ancient burial rite. Warriors, in particular, were given arrows to use in the afterlife. Then again, it could be that the person was fatally shot and nobody bothered to remove the shaft before burial.[3]

7 The Golden Mask

Similar to Egypt, Bulgaria has its own “Valley of the Kings.” Instead of tombs filled with pharaohs, the landscape is filled with Thracian burial mounds. But in 2004, archaeologists made a discovery that they claim is on par with the treasures of the Greek warrior-king Agamemnon and Tutankhamen. More precisely, their death masks. While digging in the valley, the team found a massive tomb. It was shaped by six stone slabs that collectively weighed nearly 12 tons. It was not the mega grave that aroused excitement but a solid gold mask found within. A lightweight compared to the stone walls, it weighed 0.45 kilograms (1 lb).[4] But it was a unique find from the Thracian culture, which flourished 2,400 years ago. The funeral mask and enormous tomb show that the Greeks and Egyptians were not the only great ancient civilizations. Indeed, at their height, the people of Thrace ruled modern-day Bulgaria and held territories in Macedonia, Romania, Turkey, and Greece.

6 A Roman Bath House

In 2016, an archaeologist drove past a building site in the city of Plovdiv in southern Bulgaria. She was horrified when she recognized ancient tiles among the construction rubble. Also, workers had already destroyed an old, valuable wall. An attempt to inform those responsible for the project was met with a nasty attitude. However, the Plovdiv Municipality ordered emergency archaeological excavations. What they discovered was the ancient city’s best find of the year—the pristine walls of a Roman thermae (public bathhouse). It was not a one-tub affair, either, but a large structure with remarkable architecture. The thermae was constructed in the second century AD when more of Plovdiv’s historic landmarks were created. These include the most celebrated, the Antiquity Theater, and the Ancient Roman Stadium. The area surrounding the thermae may hold more surprises. However, most of the land is private property with dense housing. This makes it difficult to dig up more of the region’s history.[5]

5 Two-Millennia-Old Ship

After 2,000 years, one would expect a ship to be destroyed by nature and generations of hungry wood eaters, especially if it sunk in the ocean. Not so for one plucky Roman vessel. In Bulgaria’s Black Sea, the highly preserved ship was found among 60 others from different eras. In 2017, the Roman ship became the last and most remarkable of an underwater archaeological expedition that ran several seasons. What made the wreck exceptional was the perfect preservation of certain parts. Found on the Bulgarian shelf about 2,000 meters (6,600 ft) below the surface, it showed a standing mast, both quarter rudders, and yards on the deck. Researchers even found 2,000-year-old rope, a shipment of amphorae in the bow, cooking pots, and rigging. The rarest was a capstan, a deck device used to move heavy weights. Previously, it had only been seen in ancient drawings. The reason why the ship, as well as most of the other vessels, pickled so well is because the Black Sea’s water is anoxic. Below 150 meters (500 ft), organisms that usually feed on wood cannot survive.[6]

4 Europe’s Oldest Town

Found in 2012 in northeast Bulgaria, Europe’s oldest prehistoric town was home to salt specialists. Residents once boiled spring water to produce bricks of salt. Since it was an extremely valuable commodity, the salt mining may have made the town a target.[7] Thankfully, archaeologists did not find the locals’ violently strewn skeletons. But they did find an impressive stone wall around the settlement, built between 4700 and 4200 BC. The need to protect the salt sources could be why the town needed such tall stone fortifications. To whatever end, the wall is a unique feature from prehistoric southeast Europe. The population of around 350 enjoyed two-story homes and ritual pits and buried their dead in a small cemetery. Though it existed 1,500 years before ancient Greek culture, the town may have been a member of other mining civilizations. Bosnia and Romania have similar salt sites from the same time. These were left behind by miners who also extracted copper and gold in the Carpathian and Balkan mountains. This could explain the location of the world’s oldest gold cache. It was found a few decades ago, 35 kilometers (22 mi) outside the walled town.

3 The Kazanlak Treasure

Not all fantastic finds are extracted from the Earth as they were left centuries ago. In 2017, a car was pulled over in the town of Kazanlak for suspicious behavior. Even so, the police had no idea that they were about to save valuable artifacts from disappearing into the shadowy world of treasure hunters. Bulgaria has a rampant problem with looters. They smuggle an estimated USD 1 billion worth of artifacts out of the country every year. The men caught that night took a remarkable collection from an unknown location. Inside a wooden box, several gold and semiprecious pieces totaled about 3 kilograms (6.6 lb). They included earrings, a tiara, a bracelet, coins, and a necklace. Pottery shards and a tombstone were also found with the collection. A pair of detonators hinted at the damaging way the looters preferred to “excavate.” Since the men refused to say where they found the collection, archaeologists can only guess at its origins. They believe that it probably once belonged to a high-status woman from Kran, a medieval city from the same region.[8]

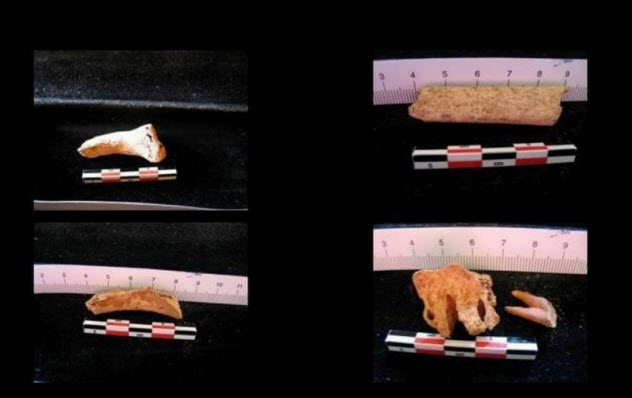

2 The Baptist Bones

In 2010, a pair of archaeologists encountered a lot of hints that they could be nearing the mortal remains of John the Baptist. In the Bible, John was the one who performed Jesus’s baptism. First, the archaeologists were on an island called Sveti Ivan (“Saint John”). While they excavated an old Bulgarian church, they found a sarcophagus near a box inscribed with Saint John’s name and his holy day (June 24). The coffin yielded the barest of a man’s skeleton—one knucklebone, an arm bone, a single tooth, a rib, and a piece of a skull. Two years after the discovery, the tests that proved they likely belonged to the same male also provided a date. The remains were placed in the early first century, a rough match with John’s living days. Analysis strongly suggested that the individual came from the Middle East, another match.[9] However, authenticating the relics beyond a shadow of a doubt remains difficult. What researchers understand even less is why somebody placed three animal bones with him. Belonging to a cow, a horse, and a sheep, they all had the same age—a curious 400 years older than the human bones.

1 Oldest Multiple-Page Book

When an anonymous donor handed over a book to Bulgaria’s National History Museum, the moment must have been surreal. Not only was it the earliest book with bound pages but the entire thing was made of gold. Even better, it was written in a lost language. The author or authors belonged to the Etruscans, an enigmatic people still not fully understood. The book is not hefty in terms of quantity, consisting of only six pages. However, each is the equivalent of 24 carats of precious metal. The creator added illustrations of a mermaid, harp, horse rider, and soldiers. The story of its discovery is as mysterious as the Etruscans, who were eradicated by the Romans during the fourth century BC. The donor claimed that he found it as a young man. (At the time of donation, he was 87.) A canal had been dug in southwestern Bulgaria and, in the process, a tomb was unearthed. The man noticed the unique gold artifact inside and kept it for 60 years.[10] Experts authenticated the manuscript and determined that it was created 2,500 years ago. In other collections around the world, around 30 additional sheets resemble those of the golden book but none of them are bound. Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages