In recent times, researchers have found fascinating alternative stories attached to known explorers, unique ships, and unexpected technical knowledge used by seafarers. Divers also continue to investigate great tragedies as well as encounter unbelievable treasures and massive ships in unexpected places.

10 New Franklin Artifacts

In 1845, Sir John Franklin sailed from Britain to find the Northwest Passage, which was said to connect the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. In one of history’s worst polar disasters, both ships, the HMS Erebus and the HMS Terror, were lost. All 129 crew members perished in the days after they abandoned the ice-trapped vessels. To solve the cause of the ill-fated voyage, the wrecks became a sought-after prize. This dream came true in 2014 (Erebus turned up in Victoria Strait) and 2016 (the Terror was found near King William Island). The real mystery was what had happened after the crew members disembarked. Graves, artifacts, and notes were found, but none gave the full story. In 2018, marine archaeologists attempted to reach Erebus but the season’s ice made conditions dangerous. It prevented the divers from reaching Franklin’s cabin and the captain’s log, which might hold clues about the fleet’s final days. Archaeologists returned with nine new artifacts, including tools and a pitcher. Previous seasons had recovered cutlery, ship parts, bottles, and buttons. Interesting as these articles may be at over 170 years old, researchers hope to find more substantial items in the future. The logbook is a real possibility because the freezing temperatures would have preserved it.[1]

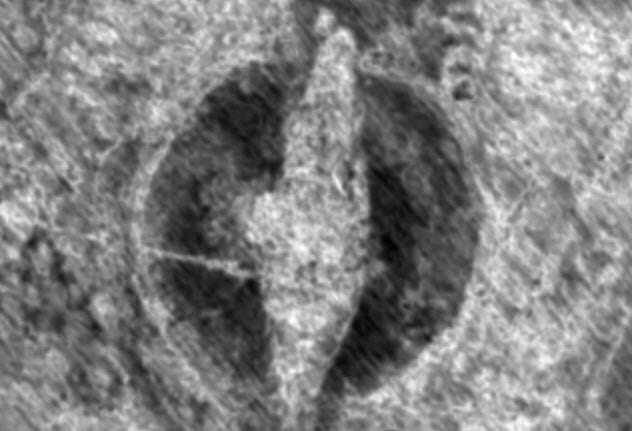

9 The Lake Serpent

In 1829, a large schooner called the Lake Serpent was carrying a shipment of limestone when it sank in Lake Erie. The ship joined a unique club—the sunken fleet of the Great Lakes. Thanks to their treacherous waters, the Great Lakes have the most shipwrecks per square mile in the world. Recently, researchers chose Lake Erie’s haystack of over 2,000 vessels to search for the Lake Serpent. As the oldest shipwreck in Lake Erie, it would be a valuable retrieval to enrich the Great Lakes’ history of transportation throughout the ages. Using old news reports and government archives, a project was launched to find the Serpent. Scans found a small object near Kelleys Island. Although it was initially dismissed as a rock, a diving expedition discovered that the object was a wooden schooner.[2] Time had reduced its original size, but several clues suggested this was the Serpent. Records mentioned a snake carving on the bow, and divers found signs of a bow carving as well as signature limestone boulders in the hold.

8 Tar Made Vikings Successful

The Vikings terrorized much of Europe in the eighth century, and their seafaring skills even took their longboats across the Atlantic. The secret behind the sturdy vessels (and the ability to do some widespread pillaging) was tar. This surprising technological innovation was discovered by accident. In recent times, road workers in Scandinavia came across large pits. Tests dated them between AD 680–900 when the Vikings began to emerge as a powerful threat. Archaeologists recognized the structures as kilns and, eventually, as a site where tar was produced on an industrial scale. The location was also a pine forest. The Vikings used pine wood as a key ingredient to make the substance.[3] Investigations showed that the kilns made enough to waterproof fleets of longships. The Norsemen’s raiding success lasted centuries. If they had never figured out how to turn pine trees into tar, history would look quite different.

7 Treasure Hunters Versus Florida

Salvaging company Global Marine Exploration (GME) hit their dream in 2016. Near Cape Canaveral, they found shipwrecks containing some of the oldest European artifacts in American waters. GME believed that their share of the bounty, millions of dollars, would be paid. They found the wrecks while operating under six permits approved by the state of Florida. GME followed procedure and reported their find. Instead, the team was told that everything they had found belonged to France. When France made the claim, Florida backed up the country and not the company. A judge ruled that the ships were from French expeditions (1562 and 1565). However, GME’s research showed that the wrecks were likely Spanish and the valuable French artifacts (cannons and a marble monument) were looted from a French colony. Fort Caroline had suffered a Spanish massacre in 1565, and the monument matches the description of a known Fort Caroline structure.[4] GME said that they could prove it under a permit to bring artifacts up for identification—the one permit Florida never gave them. GME continues to fight for $110 million, claiming a conspiracy between Florida officials and France to block the discoverers’ share.

6 The Endeavour Candidate

The HMS Endeavour is among the world’s most wanted shipwrecks. She carried Captain James Cook on his historic voyage and was the first European ship to sail to the east coast of Australia (1770). For most, the Endeavour‘s story ends there. However, the ship had a fascinating post-Cook life. Renamed the Lord Sandwich 2, it became a British prison that housed American soldiers during the War of Independence. As tensions rose in 1778 and the Battle of Rhode Island loomed, Cook’s ship was one of 13 scuttled to form a blockade near Rhode Island. In 2018, archaeologists found a jumble of wrecks near the East Coast of the US. Discovered at Newport, the location of the 1778 blockade, one ship showed promise. The timbers matched the hull dimensions of the Endeavour.[5] However, before the remains can be confirmed, future samples must prove that the timber came from northern England, where the ship was built. The rest of the scuttled vessels were built with American or Indian wood.

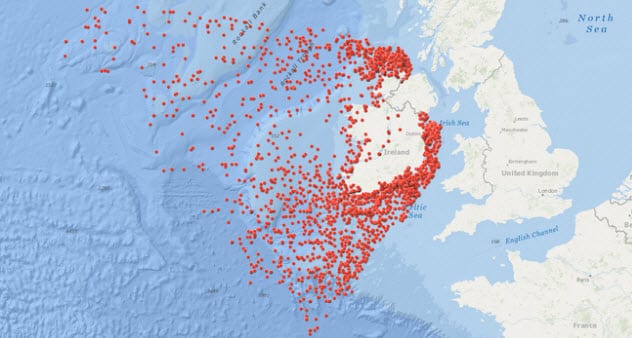

5 Mystery Ships Of Ireland

In 2018, a new map of Irish shipwrecks was released. The document was heavily mottled with 3,554 dots. Remarkably, each speck represented a vessel. They were scattered around Ireland and the North Atlantic Ocean, covering 919,445 square kilometers (355,000 mi2). As far as researchers know, the oldest date back to the 16th century. Some are known—their names and last moments are on record. The most famous is the British ocean liner, the RMS Lusitania, which sank near northeast Ireland in 1915 after a direct hit from a German torpedo. This incident was part of why the US joined World War I—as over 100 American passengers were killed. The most recent addition was an Irish fishing ship that came to grief in 2017, though everyone survived. However, most of the shipwrecks have no identity. Nobody knows their names or what disaster overcame the crews. It is a complete mystery. The most incredible thing about the underwater fleet is that the map is incomplete. The dots represent a fifth of the real number. According to the Irish government’s records, 14,414 other ships wrecked around Ireland but their locations are unknown.[6]

4 Rare Viking Burial

A famous landmark in Norway is the massive Jelle mound. Located near the Rv41 118 freeway, the mound has already yielded many finds from the Viking era. These included eight burial mounds and the outlines of five longhouses. Though the Jelle monument was an ancient grave, archaeologists never investigated it. The assumption that farmers and looters had removed everything of value came to a sobering correction in 2018. Ground-penetrating radar peered inside the mound and revealed a boat measuring 20 meters (66 ft) long. Adding to the surprise, the radar also found the extra burial mounds and longhouses in the area. The ship was a mere 51 centimeters (20 in) below the surface. It was an incredibly rare Viking boat burial, likely from around AD 800. The images suggested that the bottom half was in good shape but failed to detect human remains or grave goods. Only three previous Viking boat burials have been unearthed in Norway, but this spectacular find will be the first to undergo modern-day analysis.[7]

3 The Ruddock Claims

Alwyn Ruddock was a historian who died in 2005. She extensively researched early British explorers, including William Weston and John Cabot. A surviving Ruddock paper made startling claims about them. But with her work destroyed (her death wish), there was no real evidence. It was already known that King Henry VII supported Weston’s expedition to explore the New World. In 2018, researchers combed through old tax scrolls to study Bristol-based voyages, including Weston’s. By accident, a 500-year-old entry provided the first evidence for Ruddock’s claims. It revealed that the king rewarded Weston with a huge sum, clearly pleased with the explorer. One of Ruddock’s claims was that Cabot’s 1498 expedition took along friars who founded Europe’s first church in North America. She also said that Weston visited this Newfoundland settlement in 1499 before sailing along Labrador to find the Northwest Passage. Researchers believe this was why the king rewarded Weston so richly.[8] Non-Ruddock records showed that Cabot was also rewarded in 1498 before he sailed and the fate of his ships remains unknown. However, Ruddock’s research stated that he had explored most of North America’s east coast by 1500. The tax finding is a positive step to prove this unknown history, likely already discovered by Ruddock.

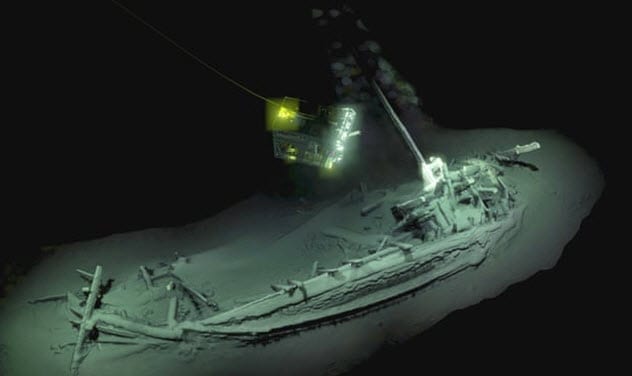

2 World’s Oldest Intact Shipwreck

The ocean is littered with shipwrecks that look like clones fractured into gray anonymity. In 2018, one came to light with a special distinction. At the bottom of the Black Sea rested the most ancient ship to be found in one piece. The vessel measured 23 meters (75 ft) long and still had its rudders, mast, and rowing benches. At nearly 2,400 years old, it had sailed the classical world and appeared to have been undisturbed since the day it had sunk. The remarkable preservation was due to the lack of oxygen at that depth, which was about 1.6 kilometers (1 mi) down.[9] The age and completeness of the ship was so rare that most researchers had never thought that such a find was possible. The vessel’s appearance closely matched a ship on a Greek vase dating to the same period. Remarkably, this is the first time that a real ship had matched the kind depicted on this type of pottery. The paintings suggested that the wreck was an ancient Greek trading vessel. Whatever it turns out to be, the craft is already earmarked to change what scientists know about ancient shipbuilding and seafaring.

1 Holy Grail Of Shipwrecks

In 1708, a Spanish galleon ship, the San Jose, sank during a battle against the British. As it disappeared into the Caribbean Sea, it took a great treasure to the bottom. A stash of precious metals, jewels, and artifacts made this vessel the holy grail sought by treasure hunters and archaeologists. In 2015, the wreck, worth up to $17 billion, was found. The discovery was kept secret to confirm the ship’s identity and protect it from looters. Besides the obvious wealth, the artifacts aboard also hold significant historical information about 18th-century life in Europe.[10] The vessel was detected about 600 meters (2,000 ft) below the surface and was partially buried. A deep-sea vehicle was lowered to film the wreckage, and at one point, it captured footage of cannons. They were an exact match to the San Jose‘s decorated bronze cannons. This conclusively identified the ship, and researchers were allowed to go public in 2018. Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages