Walt was a creative and entertainment genius, not only in his own right, but also amassing a trove of talented artists who produced some of the longest standing film classics of the previous century. However, during Walt’s lifetime only a few of his animated features made a profit at the box office. The studio was often on the verge of bankruptcy. Together with his brother Roy, Walt managed to run a multi-million dollar entertainment empire with marketing prowess to be envied. Long before home video was invented, they re-released each feature every seven years, so a new audience could enjoy them. So eventually, every film made money. But initially, most of Walt’s efforts were flops. Here is a list of his biggest box office bombs. While box office and budget numbers are scarce for some of these films, their placement on the list is a reflection of profits and losses as listed in the company’s annual report the year of the film’s release.

It’s not really fair to list this little gem of a film as a failure. Over the years it has garnered millions in box office receipts, not to mention home video sales and rentals. But in 1941 and ’42, though well received, it had an uphill battle helping the Mouse House get out of the red. At a modest budget of between 800 and 900 thousand dollars, it is Disney’s least expensive film. It was Walt’s 4th feature, following the very expensive Snow White ($1.8 mil), Pinocchio ($2.5 mil) and Fantasia ($2.3 mil). It had great pre-release buzz and was all set to appear on the cover of Newsweek for its release, but was displaced by the events at Pearl Harbor. With the European markets cut off, the flying elephant was able to make back its cost, but just barely.

It is quite possible that the only reason this classic made any money at all is because it was in the post-Sleeping Beauty era of slash and burn budgets (more on that later). Audiences seemed to like the Arthurian tale more than the critics did, but the boy who would be king was a sluggish performer. At the time, the kids were all wanting to see those zany Merlin Jones movies with Tommy Kirk and (yowza) Annette Funicello!

This was the last of Walt’s compilation films. Made up of two stories, The Legend of Sleepy Hollow and The Wind and the Willows, it got a lukewarm reception from audiences and critics alike. Over the years, it has been edited into two separate films and released in a number of different formats, Ichabod being a Halloween favorite. Of course, Mr. Toad inspired the popular ride at Disneyland and Disneyworld, where you follow Toad’s adventures… ending up in Hell. Seriously… You rode a car through Hell, complete with dancing demons. The Florida version was replaced a few years ago by a Winnie the Pooh romp that skips the jaunt into the underworld.

After the Government helped to fund two compilation films that were moderately successful (Saludos Amigos and The Three Caballeros), Walt continued the trend on his own. They were relatively inexpensive and easy to produce, which was important in the first few years after the War. Two of the segments, Claire de Lune and Blue Bayou, were leftover concepts that weren’t used in Fantasia. However, MMM didn’t turn many heads or drive the post-war crowds into the theaters. Individual segments (like Casey at the Bat, Peter and the Wolf, and Little Toot) were eventually released separately on television and other formats, and over the years Walt made his money back.

Following the hugely successful Snow White and the Seven Dwarves, Walt produced the ambitious and artistically superior story of the little wooden boy with the built in lie detector. Its budget was nearly double Snow White’s, but it didn’t originally charm the masses as much as the Princess movie did. And wishing upon a star couldn’t fix the European markets getting cut off by the growing expanse of the Third Reich. It recouped its cost by a cool million, but the studio was still having trouble staying ahead of its growing debt. Since the little puppet made of pine became a real boy, it has grossed over $100 million.

I know, I know. This is now one of the cornerstone films of the Magic Kingdom, but it took a while to find its place on the positive side of the balance sheets. Walt knew he was in trouble financially with this one. He kept trimming it down, making it as lean as possible, not only story-wise, but also easier to complete on time and on budget. Yes, it was one of the wartime films that suffered from a lack of overseas distribution and the fact that audiences just weren’t in the mood to see a movie about a young Prince of the Forest getting shot at. James Cagney’s Yankee Doodle Dandy was all the rage that year. Go figure. On a side note, the film was art directed by Chinese immigrant Tyrus Wong (who turned 102 this year). Walt hand picked him, saying that his paintings did more than look like a forest, they felt like a forest. So much for being a racist bastard.

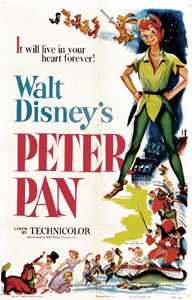

This adaptation of J.M. Barrie’s tale of the boy who wouldn’t grow up should’ve done better at first. Based on well-known and loved source material, it was a shoe-in with audiences. But it just didn’t land. Critics were merciless over Walt’s break with certain traditions. For instance, Tinkerbell was a sexpot, while she had always been played by a faceless spotlight in the stage versions. And what’s this? A boy is portraying Peter Pan? He was always played by a girl before! No, Walt, you just didn’t do it right. No wonder it eked its way to regain its $4 million budget.

Alice came out on the heels of the hugely popular Cinderella (1950). Cindy had pretty much saved the studio from bankruptcy after its postwar slump, then Alice nearly sank it again. Maybe the surreal imagery was too much for a pre-’60s America. Maybe audiences were confused and went to see the British version that was released the same year. Or maybe Walt was right when he later commented that Alice lacked heart. Like the White Rabbit, the profits were late, but better late than never.

This production was lavish on a grand scale. Walt decided to make the film in CinemaScope. The graphic style created by painter Eyvind Earle was insanely detailed and precise. It was four years in production at an unheard of cost of just over $6 million! However, At the same time, Walt was becoming more and more involved with his theme park project, thus leaving the films without a shepherd. Princess Aurora was meant to entrance the masses with her beauty, but instead she sort of put them to sleep. What do you expect when the entire cast starts yawning contagiously? Snoozefest! Hopefully, you woke up in time to see the kick-ass dragon fight at the end. On its initial release, the fair Briar Rose only managed to dream up $5.3 million. As a result of this over indulgent spending, the following film, 101 Dalmatians, had roughly half the budget …and grossed over twice as much! Since that time, SB has earned a respectable $36+ million. Sort of a sleeper hit, you might say.

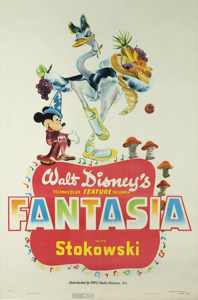

Now seen as Walt’s masterpiece, this wondrous exercise in abstract imagery nearly ruined the studio. It started out as a short, The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, but the music alone (conducted by the renowned Leopold Stokowski) cost three times the budget of the average Mickey Mouse cartoon. Rather than cut his losses, Walt upped the budget to $2.3 million and pushed ahead with his grand experiment, turning it into a feature length film. Most of his movies ran about 83 minutes, but Fantasia is over two hours. Not only were the visual effects on a massive scale, Walt’s technicians invented a multitrack stereo surround system some thirty years before THX was ever thought about. However, most theaters did not want to invest in the expensive speaker upgrade. After all, this was 1940 and the country was still recovering from the Great Depression, plus a World War was brewing in Europe, so the film only played as intended in a handful of select markets. Lackluster reviews didn’t help its tepid reception either. By the end of the decade, after multiple re-releases, it finally earned back most of its cost. It wasn’t until the 1960s when a drug-addled youth audience rediscovered the film that it started making money. Peace, love and animation. Groovy. *Snow White and the Seven Dwarves through Wreck-It Ralph. This number does not include the live action films with animated segments, like Song of the South, So Dear to my Heart, Mary Poppins, etc. It also does not include the features produced by Disney Toon Studios (e.g. A Goofy Movie), Pixar, ImageMovers Digital (e.g. A Christmas Carol), or stop motion films (e.g. Frankenweenie). ** This includes The Jungle Book even though it was completed and released the year following Walt’s death. Walt was heavily involved in its production. Though The Aristocats was in development before Walt died, it was not very far along and the final product bears little resemblance to where he left off. Sources: 1. The Disney Studio Story – Richard Holliss & Brian Sibley, 1988, Crown Pub. 2. Bambi: The Story and the Film – Frank Thomas & Ollie Johnston, 1990, Stewart Tabori & Chang Pub. 3. Fantasia – John Culhane, 1983, Abrams Pub. 4. Walt Disney’s America – Christopher Finch, 1978, Abbeville Press