A couple seek to educate readers about the natural world or the wonders of mechanical inventions and discoveries. One is a purveyor of smut, another a favorite among professional, but private, soldiers. Despite often promising beginnings and long-term success, these popular magazines have also each been at the center of controversies so shocking as to be, in some cases, literally unbelievable. 10 Cool Magazines From The Past You’ll Want To Get Your Hands On

10 Consumer Reports: Safety Seat Tests

Well-respected, Consumer Reports, the monthly publication of the American nonprofit organization of the same name, came under fire in 1988 after it had incorrectly tested the effectiveness of automobile child safety seats. Its findings? Only two of 12 tested seats passed the test, the others having failed “disastrously.” Parents concluded, from the report, that most of the costly child safety seats they’d bought to protect their children were apt to be worthless. Nothing was wrong with the seats, The New York Times claimed. Instead, Consumers Reports hadn’t conducted the safety tests correctly. Their organization’s findings, not the seats, were the problem. As the newspaper explained, the government’s safety administration’s “car-to-car side-impact” tests of the seats were conducted at 38 miles per hour, so Consumer Reports’s lab tests should have “simulated” the same speed in its crash tests. Instead, since the evaluations used a test sled, the tests replicated “a 70 m.p.h. car crash—nearly double what the magazine had claimed [since] a car, crashing at 38 m.p.h., transmits a force to the stationary car of about 20 m.p.h. because, unlike the sled, both vehicles move after they hit.” The Times’s opinion piece suggested that Consumer Reports’s evaluation of the safety seats was made in good faith but also stated that the organization’s good intentions were not sufficient. Their “alarming” results should have been a “warning sign.” Nevertheless, the newspaper supposed, the nonprofit could regain the public’s trust and even offered a bit of unsolicited advice concerning the steps it should take to do so: “Those of us who value its legacy expect a full public explanation of how its testing went wrong and how it will ensure that similar mistakes are avoided in the future.”

9 Cosmopolitan: Sex and Health Advice

Since its debut in 1886, Cosmopolitan has had its readers’ backs. The monthly publication has been more like a friend than a magazine, offering timely advice on important aspects of adult life, including topics of special interest to young women. Sex is a topic in almost every issue, so much so that, when the nonprofit group National Center on Sexual Exploitation found the magazine’s obsession with “sexually explicit material” too hot to handle, Walmart responded by removing the periodical from its stores’ check-outs. Women’s health, another frequently featured topic, often goes hand in hand with sexual advice in the publication’s pages. Not surprisingly, when one of the sexual health articles assured its readers that they needn’t fret about the possibility of HIV infection, since the virus rarely seemed to target heterosexuals, the article created quite a stir. It just wasn’t possible, the article added, “to transmit HIV in the ‘missionary position.’” In reality, women “were more vulnerable than men.” Despite the facts, the magazine’s editor, “Helen Gurley Brown, defended the article on national TV,” suggesting evidence to the contrary constituted nothing more than a campaign to “scare the daylights” out of young, liberated women, and, she said, she felt “quite comfortable” in telling her magazine’s 10 million readers that they could feel safe in having unprotected sex. Medical experts immediately “denounced” the article, and Dr. Anthony Fauci of the National Institutes of Health insisted that it was not factually correct and, therefore, was “potentially dangerous.” Likewise, Surgeon General C. Everett Koop felt obliged to state the facts during a Congressional meeting: “It is just not true that there is no danger from normal vaginal intercourse,” no matter what Cosmopolitan said to the contrary, and, as it turned out, it wasn’t a position that would long survive at the magazine.

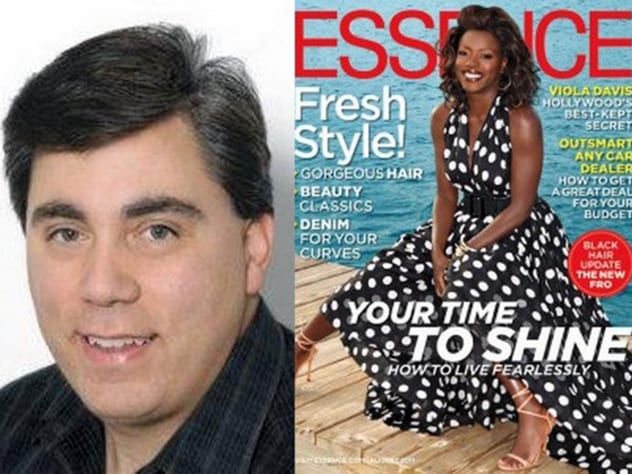

8 Essence: The Bullerdick Affair

A white man had no business controlling an African-American magazine, some readers insisted after Michael Bullerdick became Essence’s managing editor. They needn’t worry on that score, editor-in-chief Constance C. R. White, who’d hired Bullerdick, assured her loyal readers; he would not determine the magazine’s content. The readers, however, might have had cause for concern. Bullerdick’s Facebook page was plastered with posts that expressed sentiments and views antithetical to Essence’s philosophy and values. In one post, Bullerdick characterized Al Sharpton as a “Race Pimp.” Another denounced President Obama as an extremist. A third supported a critical view of Attorney General Eric Holder. The match between Bullerdick and Essence’s readers wasn’t one made in heaven. The Bullerdick affair wasn’t the first that offended Essence’s readers. They were also concerned when Ellianna Placas was named the magazine’s fashion director, a decision that failed to take into account, Dr. Boyce Watkins believes, “scores of seasoned and talented black women who can’t get jobs at other magazines.”

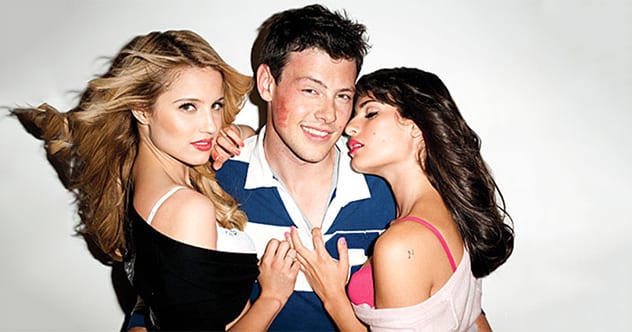

7 GQ: Sexploitation

GQ fancies itself an arbiter of style and culture, cluing its male readers in on natters of taste and lifestyle choices in a way similar to Hugh Hefner’s self-appointed role as a promoter of the Playboy Philosophy, a guide to what he saw as sophistication and the good life. In one issue, GQ decided to have a photo shoot featuring the Glee stars Dianna Agron, Lea Michele, and Cory Monteith. The feature was no doubt supposed to be suave and stylish, but The Parents Television Council, having gotten a peek at the leaked pictures, saw porn, not glamour. The watchdog group’s president, Tim Winter, denounced the photographs as “disturbing” in the way they sexualized “actresses who play high school-aged characters.” The pictures bordered “on pedophilia,” he said. GQ editor-in-chief Jim Nelson saw nothing wrong with the shoot and attributed the Council’s outrage to its members’ inability to distinguish “reality from fantasy, reminding Winter that “these ‘kids’ are in their twenties [and] Cory Montieth’s almost 30!” As adults, Nelson added, “they’re old enough to do what they want.” Agron seemed to take a middle position between that of Winter and Nelson, suggesting she understood that some people’s comfort levels might have been pushed by the more permissive and exhibitionistic turns pop culture has taken “in the land of Madonna, Britney, Miley, [and] Gossip Girl,” but parents should exercise their responsibility for the material to which they allow their children to be exposed. For her, the photo shoot, she implied, was just another gig and, although the session wasn’t her “favorite idea,” she was ready to move on and put the controversy behind her.

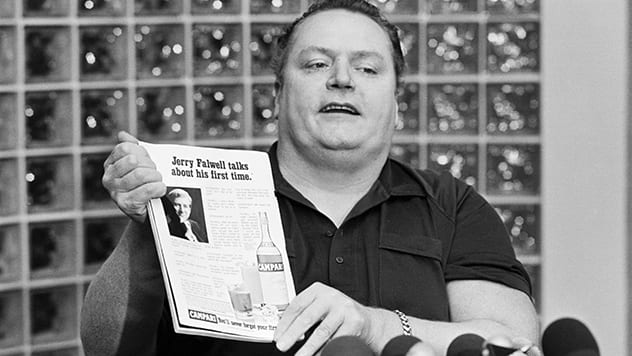

6 Hustler: Emotional Distress

The late Larry Flynt’s Hustler magazine never pretended to be anything but smut, and Flynt, who was a first-rate promoter of his many enterprises, knew how to sell his monthly periodical. Controversy, he knew, was good publicity, even if it involved offensive or distasteful material. One of his antics resulted in a lawsuit by televangelist Jerry Falwell, which wasn’t resolved until the case, Hustler Magazine v. Falwell, went before the U. S. Supreme Court. In an “ad parody” of the preacher, the magazine portrayed Falwell as telling “a fictional interviewer” that he had participated in a “drunken incestuous rendezvous with his mother in an outhouse.” The ad depicted Falwell as admitting, “I always get sloshed before I go out to the pulpit.” A federal appellate panel had upheld a $200,000 award to Falwell on the grounds that Hustler’s portrayal of the televangelist, although fictitious, was “sufficiently outrageous” to warrant such damages due to the “intentional infliction of emotional distress” it had caused Falwell to suffer. The Supreme Court unanimously disagreed with the panel’s decision and overturned the award. Speaking on behalf of himself and his fellow justices, Chief Justice Rehnquist declared that “patently offensive” speech that intentionally inflicts “emotional injury” is protected by the First Amendment when it is directed at a public figure and does not include false statements made without regard to their falsity.

5 Mad: Songs Gone Wrong

Mad, a satirical magazine that advertised its brand of wit as “humor in a jugular vein,” also resolved a legal issue before the U. S. Supreme Court. The matter arose from Mad’s parodies of the lyrics to songs written by Irving Berlin and others. For instance, the Mad piece substituted words for its song, “Louella Schwartz Describes Her Malady” (“A musical salute to one gal who enjoys being sick”) for the lyrics to Berlin’s “A Pretty Girl Is Like a Melody.” The Mad lyrics for the first stanza went: Louella Schwartz/ Describes her malady/ To anyone in sight./ She will complain!/ Dramatize every pain!/ And then she’ll wail/ How doctors fail/ To help her sleep at night. Although many might have found the Mad version humorous, Berlin was not amused, claiming Mad’s parody lyrics resulted in copyright infringement, 25 times over. Lower courts found Mad guilty of only two of the alleged counts. On appeal, the Second Circuit Court ruled that “we doubt that even so eminent a composer as Irving Berlin should be permitted to claim a property interest in iambic pentameter” and ruled that “parody and satire are deserving of substantial freedom.” The U. S. Supreme Court agreed with the Second Circuit Court’s decision.

4 National Geographic

From its inception on January 27, 1888, the National Geographic Society has had a mission: its 33 founding members intended to share “scientific and geographical knowledge” with the world. Nine months later, the first issue of its magazine was published. It quickly became popular with the general public in 1899, when editor Gilbert H. Grosvenor replaced the publication’s dry, academic, highly technical articles with “general interest” materials, including some of the most spectacular photographs of nature ever showcased between the covers of a magazine. To aid armchair travellers, the National Geographic also included splendid maps of the far reaches of the world. As subscriptions and sales mounted, the Society funded “expeditions and research projects,” exploring the mysteries and beauty of the natural world. The magazine wasn’t without controversies, however, one of the most significant of which was the racism that it exhibited at times, as editor Susan Goldberg admitted. Until the 1970s, the magazine routinely ignored Americans unless they were white, reducing them to the status of laborers or domestic servants. It also propagated “every type of cliché,” she said. In response to the magazine’s request that past issues be reviewed during the 50th anniversary of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s, assassination, University of Virginia Associate Professor John Edwin Mason uncovered material that left Goldberg “speechless.” A 1916 photograph of Australian aborigines bore the caption, “South Australian Blackfellows. These savages rank lowest in intelligence of all human beings.” National Geographic, a publication “with tremendous authority,” had, Mason said, reinforced “racist attitudes.”

3 Popular Mechanics: UFO

Between 1902, the year it was founded, and 1952, the number of Popular Mechanics’s fans grew from “a handful” of subscribers to “many millions of readers.” For the magazine’s founder, Henry Haven Windsor, a world of inventions, including “the new horseless carriage, balloon flights, [and] telegraphy” were clear indications that “a mechanical age [was] awakening.” He invested his life’s savings in publishing Popular Mechanics, renting an office, hiring a mail clerk and a bookkeeper, and struggling to survive on a tiny number of subscriptions, newsstand sales, and ads. Despite bills, his inability to meet payroll on many occasions, and the ever-present threat of imminent bankruptcy, Windsor persisted, writing the contents of the entire magazine himself, in a way that was readily comprehensible (“Written So You Can Understand It” was the magazine’s motto), and generously illustrating his articles with photographs and illustrations, many of which showed unlikely inventions, such as the “auto-sleigh,” which ran on blades rather than tires; a bicycle that boasted seven wheels and could accommodate five riders at once; and plenty of illustrated do-it-yourself projects, including a build-it-yourself house. In 2020, though, an article published in the magazine caused some readers to lose faith in Popular Mechanics. “Leaked Government Photo Shows ‘Motionless, Cube-Shaped’ UFO” showed nothing of the kind. What the picture did show, Committee for Skeptical Inquiry investigators Kenny Biddle and Mick West concluded, was simply a Mylar balloon. The misidentification of the object severely disappointed one reader, who “felt a sense of extreme disappointment with the magazine [and] its author,” who should have researched the phenomenon. As a result, the fan declared, Popular Mechanics had lost a once-devoted reader, who now had “no desire to pick up another issue.”

2 Rolling Stone: Defamation

A counter-cultural hit since it first hit the stands in 1967, alternative magazine Rolling Stone came under intense criticism after publishing “A Rape on Campus,” a story that uncritically reported allegations of gang rape at the University of Virginia. The Washington Post newspaper pointed out glaring mistakes, holes, and discrepancies in reporter Sabrina Erdely’s account of the alleged crimes. The reporter hadn’t even met with some of the accusers, and she speculated about important details, rather than relying on interviews, research, or investigative journalism. In 2016, the magazine was found guilty of defamation because of its “discredited story,” and both the publisher and Erdely were likewise “found liable.” Rolling Stone also faced additional lawsuits, some for millions of dollars.

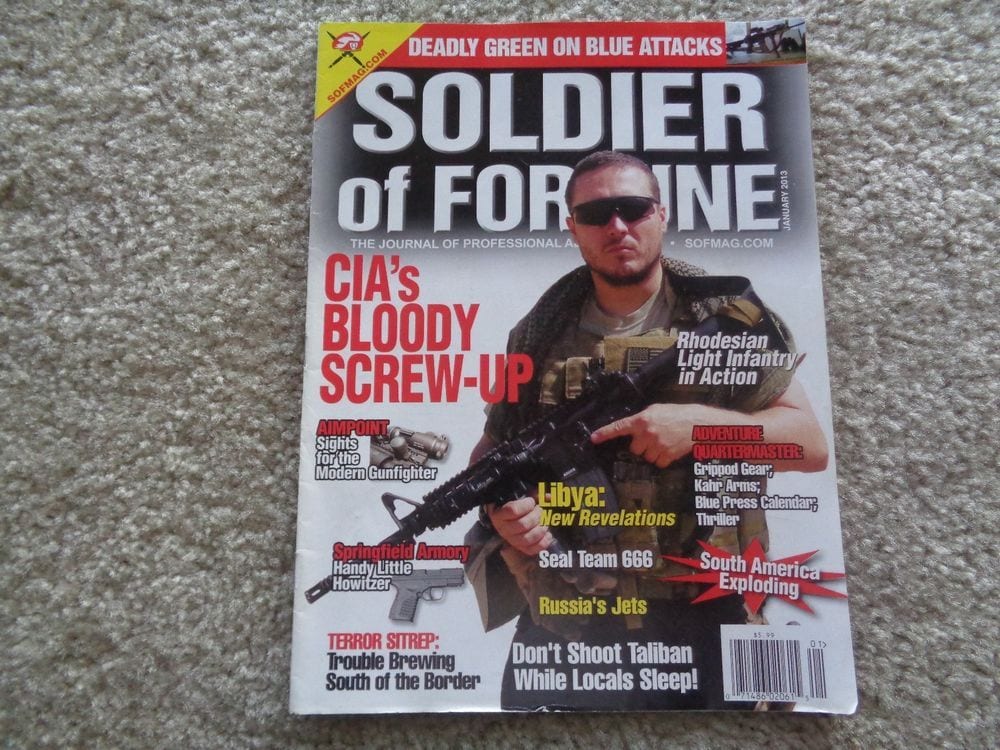

1 Soldier of Fortune: Murder for Hire

According to its subtitle, Soldier of Fortune magazine wasn’t targeted at mercenaries. Rather, it aimed at “professional adventurers” interested in war, counter-terrorism, and the like. It was deployed in 1975, by Lt. Col. Robert K. Brown, a Vietnam-era Green Beret. It went out of print in 2016, when it went digital instead. At the height of its publication, the magazine had almost a million readers. During its print run, Soldier of Fortune was the subject of multiple lawsuits. In one such action, in 1993, the magazine was held liable for a contract killing committed by murderers hired through a classified advertisement in the magazine. Although the plaintiff won a $4.3 million judgment against Omega Group, the publication’s “corporate entity,” Brown managed to settle the case for $200,000. The magazine never ran such an advertisement again. Top 10 Bizarre Magazines You Can Buy Today