10 The Islandmagee Witches

In September 1710, an old widow of a local priest was staying in Knowehead House in the rural region of Islandmagee, Ireland. Her stay was plagued by mysterious events, such as invisible hands hurling stones at windows. Household objects disappeared and reappeared, and bedclothes were rearranged in the shape of a corpse. The widow even saw a frightening demonic creature warning her that she would die soon. The apparition was not joking. On February 21, 1711, the widow died after experiencing a series of stabbing pains in her back. The locals immediately suspected that witches had something to do with the widow’s terrible fate. After a young girl called Mary Dunbar found a strange apron containing the bonnet of the dead widow, supernatural events started to happen around her, too.[1] She appeared to be possessed, vomited small household objects like pins and buttons, and even levitated above her bed. After a month of torment, Mary managed to name eight women from the area as the witches responsible for the events. This was based on the way their spirit images had been visiting her. The local clergy started investigating the case with Edward Clements, the mayor of the nearby Carrickfergus. (He was an ancestor of Samuel Clemens, whom you might know better as Mark Twain.) The eight women were taken to court despite their pleas of innocence. There was very little actual proof against them apart from Mary’s accusations and eyewitness reports of her convulsions. Even so, the “witches” were sentenced to a year’s imprisonment in a filthy prison (because the judge probably wasn’t happy about killing witches, especially ones who could apparently visit him in his sleep). The Islandmagee witches became one of the creepier stories in the area’s folklore. Although modern scholars think that the women were innocent, it’s worth noting that their sentences are still in effect. They’re still witches in the eyes of history.

9 The Great Scottish Witch Hunt Of 1661–62

The biggest witch hunt in Scotland’s history spread like wildfire. It started in the small areas near Edinburgh, where over 200 people were accused of witchcraft in just nine months. Then the frenzy moved on to the rest of the country. Before 1662 ended, a total of 660 people had been accused. Reports on how many of these people were actually executed vary. There is hard evidence of 65 executions (and one suicide). But some estimates put the number of killed “witches” as high as 450, although they do expand the timeline to 1660–1663. Historians usually attribute the sudden, violent hunt to the end of English rule in the area. English judges had been unwilling to prosecute suspected Scottish witches. So once the English went away, the Scots started rapidly going through their accumulated supply of strange old crones. Local church officials also played a part in the hunt, seeing and taking the opportunity to reestablish themselves as powerful players now that the English had gone. The story behind the Great Scottish Witch Hunt’s end is much simpler. The secular authorities just grew tired of the witch panic. A number of suspected witches were acquitted, some of the more zealous witch-prickers[2] (the people in charge of finding the witches) were arrested, and no more trials were authorized. Just like that, the greatest witch hunt that Scotland would ever see was no more.

8 The Doruchowo Trials

Many people forget that the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was a massive European superpower in its day. At the height of its powers in the 16th and 17th centuries, it was one of the biggest and most powerful early modern states on the Continent and its attitudes toward religion and democracy were surprisingly tolerant. This makes it all the more surprising that the country was involved in one of the latest mass witch trials in Europe. The Doruchowo Trials saw the officials of the town of Doruchowo try and execute no less than 14 supposed witches from the village of Glabowo. This happened in 1775. Even a century earlier, this kind of mass trial and execution would have been unacceptable in countries like England. Strangely enough, it was very much unacceptable in Doruchowo, too. The Commonwealth’s central parliament, the Sejm, had already forbidden village judges from trying witches in 1745 on pain of death. When this wasn’t enough, their highest court also prohibited the more powerful town judges from witch cases in 1768.[3] However, Doruchowo officials apparently really hated witches, which led to their campaign against witchcraft (and law) seven years after the fact. This was the last straw for the Sejm. Immediately after learning about the Doruchowo incident, they outlawed all witchcraft trials in the whole country. This finally did the trick. After Doruchowo, the country’s official records show no mention about prosecuting witches.

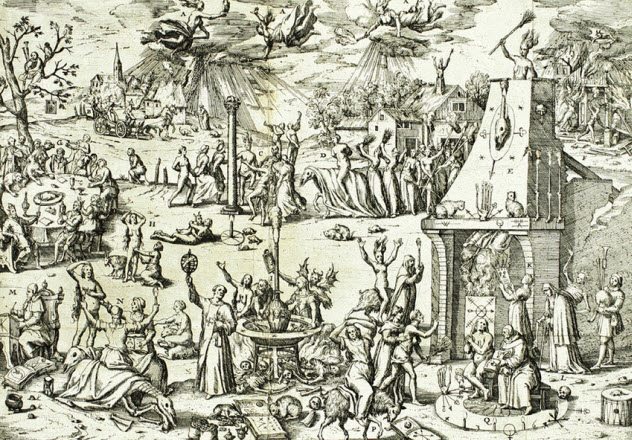

7 Trier Witch Trials

The Trier Witch Trials of Germany (1582–1594) were a major instance of large-scale persecution in the archbishopric of Trier. The area had been plagued by poor weather and failed harvests for years. Once the public’s accusing eye turned to witches, the ruling class started openly encouraging this behavior. The trials were chiefly orchestrated by Peter Binsfeld, who went on to become an infamous witch hunter. A bishop at the time, Binsfeld operated under the authority of Prince-Archbishop Johann von Schonenburg.[4] He and his cohorts didn’t just target suspicious old women like most witch hunts. Powerful people were also open targets. When Trier’s deputy governor, a judge called Dr. Dietrich Flade, attempted to rein in the witch-burning madness, he was tortured into confession and burned at the stake in 1589. Several other notables experienced the same fate. The Trier region spent over a decade in full witch-hunting mode, sentencing people to death left and right while people like notaries and executioners grew rich from other people’s misery. When the smoke cleared, at least 368 people had been burned to death. One of the few who managed to save himself from this terrible fate was Cornelius Loos. A scholar who actively protested the witch trials, Loos wrote a book about his views. But the manuscript was confiscated, and Loos himself was thrown in prison. However, in 1593, he managed to give such an elegant recantation of his views that the officials eventually pardoned him. Later, Loos moved to Brussels and once again ended up in prison for his anti–witch hunt views. The man was not a quitter.

6 Northampton Witch Trials

The 1612 Northampton Witch Trials started like presumably many others in that era: with the nobility accusing common women of witchery. The main accuser was Elizabeth Belcher, who disliked a young lady called Joan Browne. Elizabeth started claiming that the girl had put a curse on her. When Elizabeth fell ill soon afterward, that’s all she needed to take things to court. Her brother William Avery joined in on the accusations, claiming that he had tried to go to the Browne cottage to lift the curse, but an invisible barrier had held him back. Joan Browne, her old mother Agnes, and four others were arrested for witchcraft and sentenced to hang. There was never much hope for them because “innocent until proven guilty” was an unknown concept in those days. When someone brought you to court, everyone assumed you had done something to deserve it. The story says that before they were hanged, William Avery was even allowed to enter the women’s cells and beat old Agnes Browne bloody—because spilling a witch’s blood was thought to lift her curses. In the same year, Northampton also hanged a man called Arthur Bill, who supposedly “bewitched” a woman to death along with some cattle. Arthur was reputedly from a witching family, so people already suspected he was on the side of evil.[5] The accusations ended up ripping the whole family apart. Although Arthur pleaded innocence, his father “defected” from witchcraft and testified against him. Arthur’s mother ended up slitting her own throat out of fear of being hanged as well.

5 The Flowing Wells School Witch

In 1969, Flowing Wells High School in Tucson, Arizona, became entangled in one of the strangest witch hunt cases in history. A folklore lecturer from the local university visited the school and held a presentation that featured a description of what he said were traditional witches: blonde hair, blue or green eyes, a widow’s peak, a pointy left ear, and a penchant to wear a shade called “devil’s green.” This description happened to match Ann Stewart, a tenured teacher in the school, almost perfectly. Of course, the students started joking about it. Stewart decided to let them have their fun. So when she was asked whether she really was a witch, her reply was simply: “What do you think?” This turned out to be a mistake. Rumors started spreading. At first, Stewart quite enjoyed her new image. She threw gasoline on the flames by giving her literature student a suggestion to find out about astrology and even dressed up to play the part of the witch for a folklore lesson at the request of another teacher. However, she was just taking things in stride and never referred to herself as a witch. Unfortunately, the school district wasn’t amused by her antics. In 1971, they fired her for “passing herself as a witch and teaching witchcraft to students.”[6] In a delicious twist, Stewart brought this particular witch trial to court herself. The judge ruled in her favor and ordered that she had to be immediately reinstated. So, this particular witch hunt had a rare happy ending for the “witch,” who got to keep both her job and her reputation. Still, Stewart knows perfectly well that things would have gone very differently in the past. “I surely would have been burned at the stake by now if this was 18th-century Salem,” she says about the ordeal.

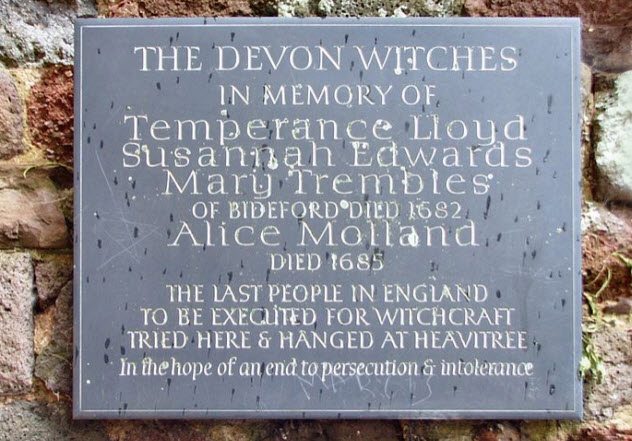

4 Trial Of The Bideford Three

In 1682, three women from Bideford in Devon went down in history in a way that they probably would have preferred to avoid. They became the last people in England who were hanged for witchcraft. It’s not known what Temperance Lloyd, Mary Trembles, and Susannah Edwards really did. They were accused of making local women Grace Thomas and Grace Barnes sick and conspiring to kill them.[7] Temperance Lloyd reportedly confessed that she was dealing with “the black man,” a folklore version of the Devil. However, all three pleaded innocent during their trial. This didn’t help, and the “Bideford witches” were hanged at Heavitree outside the city. Although the Bideford witches are long dead, their case is still strangely active. Modern British witches have taken their fate to heart. They have raised a plaque to the Bideford Three and even staged protests near the local Exeter Castle, demanding that Temperance, Susannah, and Mary be posthumously pardoned.

3 Val Camonica Witch Trials

The people of Val Camonica probably never knew that they were witches, pagans, and heretics. The area was remote and mountainous and only technically governed by the republic of Venice. Unfortunately, the church didn’t care about their ignorance. In 1455, a foreign inquisitor first visited the area and was horrified enough that he enlisted the aid of local authorities. They accused (and presumably executed) an “unspecified number” of the area’s inhabitants for “rejecting sacraments, immolating children, and adoring the Devil.”[8] Whether the Val Camonicans actually sacrificed children is hard to say, but the area left such an impression on the Inquisition that they returned to haunt the area from 1505 to 1510 and again from 1518 to 1521. During these purges, an estimated 100 people were burned as witches, generally thanks to forced confessions, misleading questions, and outright torture. The inquisitors never bothered informing Venice about their activities in the area. When the Venetian Council of Ten learned about the witch hunt, they were mystified. After all, they knew that the people of Val Camonica were simple, backward folk who were unlikely to be in league with demons. Venice quickly removed the leading inquisitor from Val Camonica, expressed their disgust over the witch hunt, and even stated that the Inquisition’s victims in the area had died as martyrs.

2 Suffolk Witch Hunts

In 1645, the appropriately named Bury St. Edmunds in Suffolk, East Anglia, became the scene for the largest single witch trial in England. The trial, where 18 people were hanged, was orchestrated by Matthew Hopkins, a self-styled “witchfinder general” who roamed the area at the time. The Bury St. Edmunds trial was far from the only one he and his cohorts arranged in Suffolk. In 1645 alone, they had 124 witch trials in the area. The targets were usually poor, elderly women, although in some cases, men and wealthier citizens were also targeted. One of the more famous male victims was the 80-year-old Reverend John Lowes of Brandeston, who had a penchant for long-running feuds and seemed a little bit too high on his horse for many people. So he was named a witch. One violent interrogation and hasty trial later, he was also hanged as one.[9] These terrifying events were a combination of turbulent, war-torn times, religious fervor, and the 1603 law that outlawed witches. People like the “witchfinder general” Hopkins saw their chance to fill their pockets at the expense of poor, defenseless people who seemed suspicious, so they used that chance to the best of their ability.

1 The Northern Moravia Witch Trials

Northern Moravia, a historical area in the Czech Republic, was not a good place for perceived witches in the latter half of the 17th century. During that time, hundreds of women were burned at the stake as witches, and a single witch trial could lead to over 100 executions. One particular tragedy started during a mass when an altar boy saw that an old lady had pocketed her Communion bread instead of eating it. When a priest confronted the woman about this, she explained that she was going to give the bread to her cow to increase its milk production. The priest took this as a sign of witchcraft and alerted a judge who specialized in such cases. Unfortunately, the justice system of the time actually derived revenue from trials. As the judges and courts sentenced more and more people for public burnings, they sustained their income by finding more “witches” to prosecute and execute. Their methods for finding new victims involved gathering accusations of witchcraft from “concerned citizens” and, of course, the tried and tested method of prisoner torture.[10] Eventually, the body count grew so high that the area’s ruling class started getting concerned. Surely, it was just a matter of time before they or someone they cared about would fall victim to the witch hunt. With all their power, they started putting political pressure on the government to stop the trials. This ultimately happened, and the people of Northern Moravia were left to wonder how on Earth they had condoned a brutal mass murder for so long.

+ The Witch Arrests Of Malawi

In the African country of Malawi, belief in witchcraft is deeply ingrained in the public consciousness. Unfortunately, this means that some people want to blame most of their misfortunes on evil witches who have put them under a spell. This has led to some very strange court cases. Even today, it’s not uncommon to hear a Malawian accuse someone of witchcraft, and people even get thrown in prison for it. In a single month in 2010, at least 80 people received sentences of up to six years for practicing witchcraft. This is not entirely legal. Convicting someone for witchcraft is only possible in Malawi if the person admits to being a witch (which none of the accused did), and actually accusing someone of being a witch is illegal. Even so, these cases are said to be possible because many Malawian officials share their countrymen’s belief in witches. There has even been talk of criminalizing “witches” altogether. Still, perhaps the “witches” who actually make it to court are the lucky ones. As of 2011, violent witch hunts took place in the country on a weekly basis. Their targets are often people who are least likely to defend themselves: children, old people, and the disabled.[11] Although many officials are trying to put a stop to the witch hunt phenomenon, an estimated 75 percent of the country’s population remain witchcraft believers. Strangely, Malawi’s fascination with witchcraft isn’t a superstitious remnant from old times. It is thought to be an odd contemporary phenomenon that’s tied to the many economic and social hardships the area has been going through.