But this image conflicts sharply with her strong passions, which we will reveal to you today. These 10 surprising facts about Queen Victoria show a completely different person from the stern, no-nonsense, straitlaced figure she’s often erroneously believed to have been.

10 She Kept A Detailed Journal

Beginning in 1832 at age 13, the girl who would be crowned Queen Victoria kept a journal. At the time of her death in 1901 at age 81, her entries ran 43,000 pages. In her observations, she shared her thoughts and feelings about subjects as diverse as her prime ministers, her political opinions, and her intimate thoughts about her beloved husband, Prince Albert. “It was with some emotion that I beheld Albert—who is beautiful,” she gushed in her October 10, 1839, entry. “He clasped me in his arms, and we kissed each other again and again!” She also shared her grief at his passing. In 1885, she noted the fall of Khartoum and Major-General Charles George Gordon’s undetermined fate. She described her coronation on June 28, 1838, and the emotional ovation she received as she traveled to her Diamond Jubilee in 1897. The first book of her multivolume journal was given to her, she recalled, by her mother so that Victoria could record her journey to Wales. Although Princess Beatrice, Victoria’s daughter and private secretary, destroyed many of the original volumes of her mother’s journals, Victoria’s great-great-granddaughter, Queen Elizabeth II, has made copies of the surviving volumes available online, courtesy of the Royal Archives.[1]

9 She Proposed To Her Husband-To-Be

From the moment she first set eyes on Albert, it was love at first sight for Victoria. Since tradition forbade a suitor from proposing to the queen, it was up to Victoria to pop the question. As recorded in her journal, she did so on October 15, 1839, when she was 20 years old. According to her journal, she summoned Albert and met with him alone in a private room. She assured him that his acceptance of her proposal that they marry would delight her. She confided, “We embraced each other over and over again, and he was so kind, so affectionate.”[2] The couple were joined in marriage on February 10, 1840.

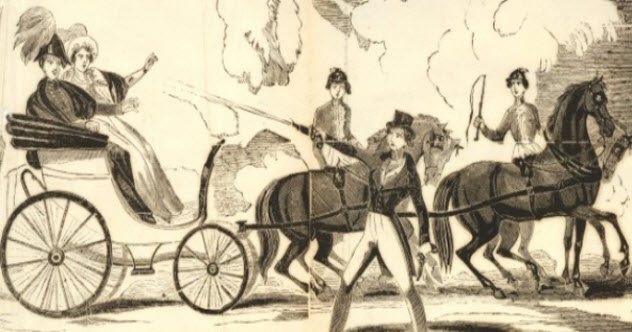

8 She Survived Eight Assassination Attempts

From 1840 to 1882, eight attempts were made to assassinate Queen Victoria. She survived them all. The first attempt to take her life occurred on June 10, 1840, when 18-year-old Edward Oxford, a bartender, twice fired his dueling pistol at the queen, who was four months pregnant with her first child. She and her husband were seated in a carriage outside Buckingham Palace. Tackled and arrested, Oxford was found guilty but insane. He spent 24 years in an asylum, ending his days in Australia after being deported from England. John Francis made two attempts on the life of Victoria. He first tried to assassinate the queen on May 29, 1842. Riding in an open carriage, she and her husband were on their way home from a church service when Francis pointed his flintlock pistol at Victoria. But his weapon failed to discharge. Jamming his pistol beneath his coat, he vanished into Green Park. The next day, Francis made his second attempt to kill the queen as the royal couple repeated their journey by carriage. They had hoped the would-be assassin would give himself away by attempting to shoot the queen again. When he did, Francis was captured and sentenced to be hanged and quartered (his body cut into four pieces after decapitation). But Victoria commuted his sentence to lifelong banishment. John William Bean, a 17-year-old man with a serious spinal deformity, also tried to assassinate Victoria. He used the same strategy as Francis had. Similarly, Bean’s weapon failed to fire. He said that his gun was more full of tobacco than gunpowder. That night, July 3, 1842, he was arrested at his family’s home and later sentenced to 18 months of hard labor. Twenty-four-year-old unemployed bricklayer William Hamilton’s chance to assassinate the queen occurred on June 19, 1849. Her birthday was being officially commemorated, and she and her three children rode in a carriage through Hyde Park and Regent’s Park. As they returned to Buckingham Palace, Hamilton fired his pistol. But he neither killed nor injured anyone. As a result of his act, he was banished to the prison colony of Gibraltar for seven years. On June 27, 1850, after visiting her dying uncle with her three children, Victoria was attacked when her carriage stopped outside the gate of Cambridge House. Eccentric British army officer Robert Pate struck her in the forehead with his cane, causing a massive bruise and a black eye. He was sent to the penal colony in Tasmania for seven years.[3] The next attempt occurred when Victoria was returning home from an outing on February 29, 1872. Seventeen-year-old Arthur O’Connor, a descendant of Irish revolutionaries who’d sneaked onto the grounds after climbing the fence surrounding Buckingham Palace, raced to the side of Victoria’s carriage. He pointed a gun at the monarch from 0.3 meters (1 ft) away. John Brown, the queen’s personal servant, tackled the would-be assassin. O’Connor received 20 strokes of a birch rod, was imprisoned for a year, and was exiled to Australia. Having taken a train from London to Windsor on March 2, 1882, Victoria was departing from the station in her carriage when she heard a noise that sounded like an engine explosion. Then she saw a man being forced down the street amid a rush of people. In reality, the noise heard by the queen was the sound of a gunshot fired by an emotionally disturbed would-be assassin, 28-year-old Roderick Maclean. Police rescued Maclean from Eton students who were beating him with their umbrellas. At his trial, he was found guilty but insane and remained in an asylum until his death.

7 She Had A Passion For Nudity

Jonathan Marsden, lead curator of the 2010 exhibition, Victoria & Albert: Art & Love, at The Queen’s Gallery in Buckingham Palace, said that the exhibits would surprise visitors who believed that Victoria was a prim and proper, if not priggish, woman. She favored nudes, whereas her husband preferred less revealing paintings and sculptures. A sculpture Albert had commissioned of himself for the queen’s 23rd birthday showed him barefoot and clad in a kilt that exposed much of his legs. The queen found a place for the statue “on a remote staircase out of the sight of visitors at Osborne House, the queen’s palace on the Isle of Wight.”[4] Although Victoria wasn’t offended, she did this because the sculpture embarrassed Albert. He thought that the piece’s bare legs and feet exposed too much flesh in that environment. So he requested a second sculpture that featured a longer kilt and sandals. For his birthdays, Victoria gave Albert paintings containing a good deal of nudity, which occupied honored places in their homes.

6 One Of Her Subjects Left Her A Fortune In His Will

Eccentric recluse John Camden Neild, Lay Rector of North Marston, leased an estate from the Deans and Canons of Windsor. Despite his considerable wealth, he refused to spend money on the property’s upkeep, letting the vicarage and outbuildings fall into disrepair. A former barrister and magistrate, he owned estates in Buckinghamshire, Kent, and Chelsea. From his father, a silversmith, he’d inherited a fortune. Upon his own demise, Neild bequeathed £500,000 to Victoria, which she used to finance repairs for the North Marston parish. From the “miser’s fortune,” the queen funded the restoration of the church’s chancel and east window. She also made a donation to reopen the parish’s National School.[5] Allegedly, part of Neild’s gift to the queen also financed her children’s weddings and improvements to Balmoral Castle. Victoria ordered the creation of a royal memorial to honor her benefactor’s memory and generosity.

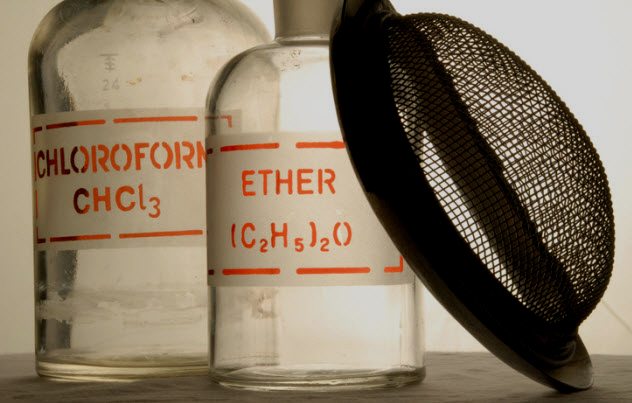

5 She Was Anesthetized As She Gave Birth

Dr. John Snow became interested in ether and chloroform early in his medical career and wrote a number of articles on these anesthetics. About midway into his career, he began working with Victoria’s physicians. Unlike Snow, her doctors were dubious about anesthesia’s safety. Perhaps at the request of Albert, Snow administered chloroform to Victoria during the delivery of her seventh child, Arthur (the future Duke of Connaught), her eighth, Leopold (the future Duke of Albany), and her last child, Princess Beatrice.[6] In each case, he used the open-drop method, in which liquid chloroform is dropped onto a mask covering the face and mouth.

4 She Averted War With The United States

At the outset of the US Civil War, Great Britain sympathized with the Confederacy. Tensions between the US and Great Britain reached a crisis point when Confederate envoys James Murray Mason and John Slidell were removed from the British ship Trent. The British considered this incident a violation of neutrality and prepared to wage war against the United States. Earl Russell, the Foreign Secretary, drafted an ultimatum laden with language sure to offend its recipients. Although he was on his deathbed, Albert revised the document, allowing the US to comply with his country’s demand that the envoys be released without loss of face. The US acquiesced, releasing Mason and Slidell. Having agreed with Albert’s approach, Victoria authorized the dispatch of the revised document. She averted what might have been a needless, expensive, and catastrophic war between her country and the US.[7]

3 She Was Twice Rumored To Have Had Love Affairs

Victoria was twice rumored to have engaged in love affairs, once before she married Albert and again after his demise. William Lamb, 2nd Viscount Melbourne, was prime minister during Victoria’s first few years as queen. She looked upon him as a father figure, and he tutored her in the complex and subtle workings of politics. In return, she forgave him for falling asleep following dinner and for snoring in the chapel. These privileges were not afforded to others, and it was not lost on those who witnessed their interactions. In matters other than those of state, Lord Melbourne’s advice wasn’t always sound. He recommended that Victoria give credence to the suggestion that Sir John Conroy had impregnated Lady Flora, a lady-in-waiting, who certainly looked pregnant. Unknown to them, Lady Flora was dying of cancer. Her tumors caused her to appear to be with child. When Lady Flora died, Victoria’s willingness to have believed the worst of her caused a scandal. Victoria’s carriage was stoned during Lady Flora’s funeral. At the theater, she was hissed. At Ascot, ladies shouted “Mrs. Melbourne” at her. Her second rumored love affair supposedly occurred after Albert’s demise. Her husband’s manservant, John Brown, was rough and coarse. But he made Victoria laugh and brought “comfort” to her as she found him entirely devoted to her. She gave him a great deal of leeway in his interactions with her, even tolerating his frequent drunkenness and allowing him to contradict her. He was with her a good deal of the time, both in the castle and on Victoria’s frequent trips to Europe and elsewhere. Tongues began to wag. Privately, Victoria was called “Mrs. Brown” and gossipers wondered whether she and Brown had married in secret, perhaps having a child together. In reality, it seems that Victoria appreciated a confidant of whose support she could be certain. After Albert’s death, Brown filled this need.[8]

2 She Gave President Hayes The Desk Used By Presidents Ever Since

Victoria gave President Rutherford B. Hayes a desk constructed from the timbers of the British Arctic Exploration ship Resolute, from which the desk takes its name. It was one of four desks built from the ship’s remains by William Evenden.[9] Victoria kept a duplicate of the one she gave Hayes, which is in Windsor Castle, and a writing table built for her private yacht, the HMY Victoria and Albert II. A smaller ladies’ version of the desk she gave Hayes was presented to the widow of US merchant and philanthropist Henry Grinnell.

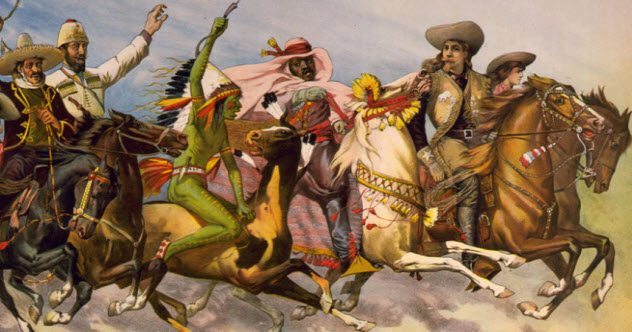

1 She Attended Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show

In 1887, Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West Show gave command performances for Victoria. The grandstands could seat 40,000 people, but she, her guests, and her entourage were the only members of the audience of 26. The queen was thrilled by the spectacle. The nearly 200 performers included cowboys, Mexican vaqueros, Annie Oakley and her husband, horses, buffalo, and a stagecoach and log cabin attacked by Indians. After the show, Victoria met Oakley and several Sioux performers, all of whom were impressed by the queen. She was awed by them as well. That night, at Windsor Castle, she described the show in her journal, marveling at the performers and “Col. Cody, ‘Buffalo Bill’ he is called, [whom she regarded as] a splendid man, handsome and gentlemanlike in manner.” Although she was a bit frightened by the painted Indians, Oglala Sioux performer Black Elk said, “We liked Grandmother England because we could see that she was a fine woman, and she was good to us. Maybe if she had been our Grandmother, it would have been better for our people.”[10]