The SAS’s first operation was launched on 16th November, 1941. It went disastrously wrong (with 40 men out of 62 being killed or captured) when sandstorms and 35mph winds scattered the SAS drops, as wells as making it impossible for them to find much of their equipment. Their second was far more successful – trucks from the Long Range Desert Group (another unit operating behind German lines) were used to drop off teams of SAS at four airfields, where they sneaked onto the runaway, and planted time-delayed explosives onto the planes before sneaking away. They succeeded in destroying 61 planes with no loss to themselves. Bob Bennett was a SAS Sergeant on the raid at Tamet airfield: “…Paddy (Lieutenant Robert ‘Paddy’ Mayne) spotted this Nissen hut affair and sneaked up to it. He obviously heard something inside because the next thing we knew he’d dragged the bloody door open and was letting rip with his tommy-gun. Screams from inside and the lights went out…the rest of us went after the planes. We got through our bombs pretty quick – brilliant those Lewes bombs. Quick and easy. Afterwards Reg Seekings said there wasn’t a bomb left for the last plane and Paddy got so pissed off that he climbed up to the cockpit and demolished it with his bare hands.” Throughout the North African campaign, the SAS managed to destroy over 200 enemy planes, a figure which was higher than the total destroyed by the RAF in the same period!

[WARNING: The clip above contains scenes of violence.] On the 30th April, 1980, 6 heavily armed terrorists burst into the Iranian Embassy in London and took 26 people hostage. They demanded autonomy for the region of Khuzestan in Iraq, and the freeing of 92 Arabs in Iranian jails. The SAS arrived on the scene quickly, and over the next 6 days of negotiations, they laid out their plans for storming the embassy, gathered information on the building itself (as well as the terrorists), and practiced the assault on a mock-up of the embassy. On the 5th May, shots were heard from inside the embassy, and the body of a hostage was dumped on the steps, outside the embassy, at 6:30. The police immediately handed over control to the SAS, and the assault teams moved into place. One team placed charges to blow out the first floor windows, whilst another abseiled down the rear of the building. At 7:23, a stunning charge which had been lowered through the skylight was detonated, and the first floor windows were blown out. Teams entered the ground, first and second floors simultaneously, clearing rooms using CS gas and stun grenades. Although the terrorists managed to kill 1 hostage and injure 2 others, the well drilled SAS men quickly killed 5 of the terrorists, and captured the 6th. This stunning success on live television catapulted the SAS from obscurity into the public consciousness.

The rebellion in Malaya started in 1948. It was an attempt to overthrow the colonial British rule, and establish a Communist government. The CTs (Communist Terrorists) set up bases in the thick jungle, and from there, launched raids and attacks against police stations, rubber plantations and tin mines. The British forces deployed in Malaya were unwilling, and unable, to operate in the primary jungle, so they concentrated their forces around the targets the terrorists were most likely to strike. As there was no need for it, the regular SAS had been disbanded at the end of the Second World War. Now, it was reformed in Malaya, with a strength of 3 squadrons. Small patrols of SAS moved deep into the jungle, and soon became skilled in jungle warfare and survival skills. Several Iban tribesman were brought in from Borneo, to teach the soldiers how to track and detect the faintest traces left by the guerrillas. The patrols operated for up to 3 months in appalling conditions – the combination of constant stress, pitiful rations and tropical diseases (many of which were new to science) led many soldiers to an early death. However, these patrols were extremely successful in ambushing CTs and denying the jungle to the enemy. They also achieved this by befriending the aboriginal tribes who lived in the jungle. Willingly, or under threat, these tribes often supplied the CTs with food. However, several SAS men learned to speak their language (Sakai) and used their medical skills to treat their various diseases, which cut off the CTs from their sources of supply. This forced the CTs to retreat further into the swamps and jungles, where they were systematically hunted down, and either killed or captured.

Oman is a small middle-eastern country ruled by Sultan Said bin Taimur. Oman had been in alliance with Britain since the 18th century, so, in 1957, when rebels led by his brother established control of a swath of territory, the sultan turned to Britain for help. Britain deployed a number of army units in Oman, but they failed to defeat the uprising. A plan to assault the rebel stronghold on the Jebel Akhdar mountain, using 4 battalions (around 4000 men), was rejected as politically impossible, so it was decided to, instead, deploy a single squadron of SAS soldiers (64 men), although another squadron later arrived. They faced a formidable task – the mountains had last been conquered almost 2000 years before, and the only way up them were narrow tracks which passed steep ravines and gorges, and were overlooked by higher ground. At 8:30, 26 January, 1959, D squadron begin to march up the south side of the mountain. Each man had to carry 54 kilos (119lbs) of equipment up 7,000 feet (2kms) of steep and difficult ground. Many men passed out, but, thankfully, the route was only lightly guarded due to a diversionary attack at Tanuf. However, a sniper’s bullet detonated a grenade in an SAS soldier’s pack, killing two SAS men and injuring a third. Nevertheless, they quickly dealt with the light resistance. Parachute supply drops to the squadron were mistaken for paratroopers by the rebels, who fled, leaving behind large amounts of equipment and supplies.

On August 25th, 2000, 11 men from the 1st Royal Irish Regiment were patrolling as part of a UN peacekeeping mission in Sierra Leone. Deep in rebel territory, their Land Rovers were surrounded by a large group of rebels, belonging to a group called ‘The West Side Boys’. They were all taken hostage and taken to the rebel camp. Over the next few days, 5 of the hostages were released, but, subsequently, negotiations broke down and the rebel leader (Foday Kallay) threatened to kill the remaining hostages. As the rebel camp was situated next to a river, SAS and SBS troops used inflatable boats to move upstream, where they set up observation posts in the jungle to gather intelligence. On the 10th of September, 2 Chinook helicopters of SAS troops launched an assault on the camp, whilst being supported by 3 Lynx helicopters, as well as a Mi-24 Hind gunship. They fast roped from the hovering helicopters into the camp, and quickly secured the hostages, with help from the observation teams who appeared from their hiding places to assault the camp. Meanwhile, a crack company of paratroopers from the Parachute Regiment attacked a nearby rebel camp to prevent it lending assistance. The rebels fought fiercely, as many were high on drugs or believed they were protected by magical amulets. However, the well trained SAS, SBS men and the paratroopers, supported by rockets, missile and machine-gun fire from the gunships, cleared the buildings in the villages one by one, and fought off any counterattacks, before the Chinooks returned to extract the troops and hostages. One SAS soldier was killed by a ricocheting round from an AK-47, and a dozen other British soldiers were wounded, whilst 18 rebels (including Foday Kallay) were captured, and at least 25 rebels killed.

The Falklands War was ignited when Argentina invaded the Falkland Islands – an archipelago over which the Argentine government has long laid a claim. In response, a British task force was assembled to retake the islands. One of the largest threats to the fleet and invasion force was the well-trained Argentine air force. An SAS observation post managed to locate a number of Pucara ground attack aircraft at a small airfield at Pebble Island. Due to the presence of civilians nearby, an airstrike was unsuitable, so an attack was authorized, and D squadron was inserted by helicopter 5 miles from the target. Whilst the destroyer HMS Glamorgan put down a barrage of fire, the SAS assault force began to destroy every aircraft they could find with explosive charges, rifle fire and 66mm rocket launchers. The fire from the Argentine garrison was almost non-existent, so the SAS only took 2 men lightly injured by a landmine. However, in the dim glow of the explosions, an SAS soldier was surprised to find two SAS NCOs (Non-commissioned Officers) brawling as the assault went in. As it happens, the two had had a long running feud, and the raid was the first opportunity they had had to settle it! The finally tally for the operation was 11 aircraft destroyed, as well as an Argentine ammunition dump.

As a part of its withdrawal from its Southeast Asian colonies, Britain attempted to form a new state composing of Malaya, Singapore, Brunei, Sarawak and North Borneo. This was to be called Malaysia. However, this formation was opposed by Indonesia, as well as many locals within the terror tribes involved. A rebellion broke out in Brunei on 8 December, 1962 – although it was quickly put down. The survivors fled into the jungle, whilst thousands of members of the Clandestine Communist Organization remained in the towns to cause riots in North Borneo and Sarawak. Parties of ‘guerrillas’ (almost certainly Indonesian troops) began to cross the border from Indonesia to carry out raids and attacks. The SAS response was to deploy a squadron to patrol the border. In order to increase the area covered by just a handful of men, the SAS soldiers befriended the local tribespeople who lived in the jungle. By living amongst them for weeks on end, calling in airdrops of supplies for the tribesmen, and treating their various injuries and aliments, the SAS gained their trust, and consequently, they reported any suspicious movements on the border to the SAS. The war then escalated, when company sized groups of Indonesian troops crossed the border in an attempt to push back British and Malayan troops to establish ‘liberated zones’. On one of these raids, their retreat tracks were located by an SAS patrol, leading to 96 Indonesian troops being killed or captured. It was then decided to take the fight to the enemy – patrols of SAS crossed the border to ambush Indonesian troops and gather information. Once an SAS patrol located an enemy camp or track, infantry groups were brought in via helicopter to set up an ambush or assault. Their success and mounting Indonesian losses led to Indonesian President Sukarno being toppled by a coup – his successor had no wish to continue the unsuccessful campaign, and by 3 September, 1966, the conflict was over.

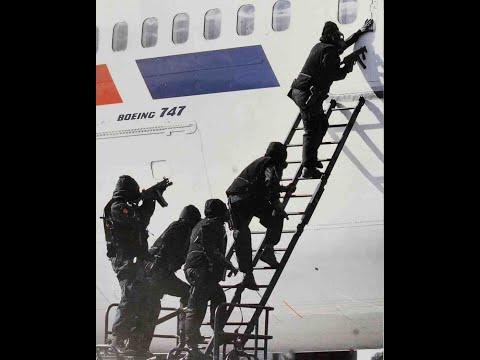

On Thursday October 13, 1977, Lufthansa Flight 181 was hijacked by 4 members of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine. The terrorists forced the pilot to fly to various airports in Rome, Cyprus, Bahrain, Dubai, Aden, and finally Mogadishu. They demanded a ransom of $15 million dollars, and the release of prisoners held in Germany and Turkey. At Aden, after a rough landing on a stretch of sand, the pilot (Captain Schumann) left the plane to inspect the landing gear for damage. When he returned to the plane, he found the terrorist’s leader (who called himself Mahmud) in a rage. Schumann was killed by a single shot in the head. The Co-pilot flew the plane to Mogadishu, where Captain Schumann’s body was dumped on the tarmac, and an ultimatum was issued for the release of the prisoners. Unbeknownst to the terrorists, they had been tailed from airport to airport by a plane containing members of the elite German anti-terrorist unit, GSG-9. They were accompanied by 2 SAS men, who provided them with a supply of newly developed stun grenades, as well as the know-how to use them. While the terrorists waited for their demands to be met, the GSG-9 team approached the aircraft under the cover of darkness, and climbed into the wings using ladders. The emergency doors were blown in, and the SAS men hurled stun grenades inside. GSG-9 soldiers stormed inside, shouting at the hostages to lie down, and opened fire. 3 terrorists were killed (including Mahmud, who died before he could detonate the grenades rigged up around the plane) and the last captured. Only 4 hostages and 1 GSG-9 man was wounded.